Deep Dive

Shownotes Transcript

Hello listeners, welcome to a new episode of Peking Hotel. I'm your host Leo. This episode is brought to you by collaboration with China Books Review, a digital magazine that publishes commentary on all things China and bookish. Fox Butterfield is a Pulitzer-winning journalist who opened the first Beijing bureau of New York Times in 1979.

Back in summer, I sat down with Fox in his home in Portland, Oregon to chat about his personal China journey. Fox grew up in a studious family. His father was a historian and the editor-in-chief of the Adams Papers. He studied Chinese history with John Fairbank at Harvard as an undergrad and graduate student. And then after spending some time in Taiwan, he worked for the New York Times as a correspondent.

He won the Pulitzer Prize as part of the New York Times team that exposed the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War and reported on the front line for a few years before becoming a China correspondent in Hong Kong. And after US and China normalized diplomatic relations, Fox went to Beijing and became the Times' first Beijing correspondent in 1949.

And after US and China normalized diplomatic relations, Fox went to Beijing and opened the Times' first Beijing bureau since 1949. This episode gives you some highlights of his journey with China. And if you're curious for more of my oral history with Fox, you can read more on the Peking Hotel Substack channel or listen to our two podcast episodes on Fox. Hope you enjoy this one.

Well, welcome to our interview. Thank you. Thank you for taking the time. Can we start by asking you your first trip to China? Could you talk about that? So my first trip to China, I was a Hong Kong correspondent for the New York Times from 1975 to 1979, because that's where in those days we covered China from. U.S. and China had not yet established relations.

And almost all the major news organizations who tried to cover China were doing it from Hong Kong. I was very frustrated that I couldn't go into China. Finally, I think in 1970, I was able to go to the Canton Trade Fair for a few days. That was my first trip to China. Any impressions from then? I can barely remember what it is.

My second trip into China was much more memorable, and that was in 1979. And the U.S. and China were about to finally normalize relations, and China, as a kind of gesture of appreciation to the United States, to Washington, decided to invite the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to come to China because U.S. officials had not been there.

And one of the senators who was on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was a guy named Joe Biden, a senator from Delaware who was in his first term as a senator. And the Senate Foreign Relations Committee invited me to come along as a New York Times correspondent with them. So I got to meet Joe Biden. And China had a shortage of hotel rooms in those days, at least for foreigners. So they made everybody room with somebody else, share a room.

And I was assigned by the Chinese government to room with the naval liaison to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who was a Navy captain named John McCain. So for two weeks, John McCain and I were roommates. We had breakfast, lunch, and dinner together. We traveled everywhere. And McCain's best friend on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was Joe Biden. So the three of us did almost everything together for two weeks. That's amazing. So that one is easy to remember.

And Joe Biden was a very nice man, very earnest. But he was a typical sort of career politician because when he went up to somebody, he always grabbed them by the hand. He's tall. He had a strong handshake and he would give them a big smile and grab their hands. And he kept doing this to Chinese who didn't really know what was going on because they're not used to being touched that way, especially not somebody almost breaking their hand. So I finally said to him, Senator,

And he'd say, don't call me Joe. I'd say, okay, Joe, please don't grab Chinese by the hand. It's kind of rude and offensive to them, and they don't understand it. He would say, well, why not? And I'd say, because that's not their custom. He'd say, okay, thank you very much. And then five minutes later, he'd do the same thing over and over again. And I kept trying to tell him, don't do that. But John McCain, I got to be good friends because I had actually seen him in Hanoi when he was in prison there. I'd gotten into Hanoi.

In 1969, as I was first starting to work for the New York Times, we then called them the North Vietnamese, they allowed me to go into the prison where he was. And I was the first reporter to find out that John McCain was still alive because he'd been shot down over Hanoi in his jet fighter. And he was very badly wounded and not in very good shape physically, but he was alive.

So I had seen him then and as roommates 10 years later in China. That's amazing. We had a great time. And I would take him out and say, let's sneak away from our handlers and see how Chinese really live and what they really say. We just went and talked to people. And he thought this was a lot of fun. How were McCain and Joe Biden like back then? Well, they had become friends. They'd become instant friends. They were really nice guys, very interested in things.

Neither one was a rocket scientist. So somehow or other, they'd become very good friends. And what were their attitudes towards China at the time? Well, neither one of them really knew too much. John McCain didn't like communists because he'd been shot down over North Vietnam and ended up in a prison for a couple of years where he was kept in very difficult confinement. He really didn't know what to expect when we were in China.

But he was happy to go around and start to talk to people. And I was very surprised at how many people would actually talk to us because very few foreigners were able to go into China at that time. And very few spoke Chinese.

So it was a new experience for all of us. Were there suspicions that foreigners, sort of people trying to hide away? Some people were scared to talk to us. Some people were afraid that they would be in trouble for talking to us. And some people said, okay, we'd like to talk. Why do you think you are interested in China, actually? When I was a sophomore at Harvard as an undergraduate,

In 1958, there was a fear in the United States that the United States was going to have to go to war with China over those two little islands, which Americans call Kamui and Matsu. And those little islands were really in the mouths of mainland harbors. But they were garrisoned by troops from Taiwan, Chinese Nationalist troops. And if China had actually attacked them, they would have taken them because they were indefensible. Yeah.

But the United States had guaranteed that they would help defend those two little islands. So in September, early October of 58, China began firing artillery at those two islands and it looked like China was going to invade them. And so there was this fear that the United States and China were going to have a war over these two very small islands that were indefensible.

And America's leading sinologist, professor of Chinese studies, John Fairbanks at Harvard, decided to have a public lecture. It was open to anybody to talk about the danger of the United States going to war with those two little islands. So I went to hear it. It was in the evening in Cambridge, Massachusetts. And he said something which in some ways was very straightforward and obvious, but I had never thought about.

He said, China is the oldest country in the world with by far the largest population in the oldest history. And it's a big, important place. And why would the United States want to go to war with China over those two little islands? It made no sense logically. And we had just finished the war in Korea. So we want to have another war like we did in Korea over those two little islands. And as I listened to him, I realized, gee, I don't know anything about that place. So I began.

going to what we call audit to just listen in to his class on the introduction to the history of East Asia. And I got really interested in China as a result of the threat of war over Jinmen and Matsu. And in the spring, I decided to take a second class in Chinese history that Fairbank was teaching. And at the end of the year, I

As undergraduates at Harvard, when you took an exam, you found out your grade because you put a postcard, a self-addressed postcard with a stamp on it, inside your exam booklet. And then the professor would send it back to you and the postcard would tell you what your grade was. And when I got my postcard back from the final exam,

It said, please come to see me in my office tomorrow morning at 10. Oh, no. So I thought, oh, no. That was a student's nightmare. I really screwed up on my exam. So I went to see him, and I was really nervous because he was a great man. He was a big figure on campus. And he was really the dean of Chinese studies in the United States. So I went in, and he said, Fox, you know, you wrote a wonderful exam. He said, have you considered majoring in Chinese history?

And I went, "Oh." No, I had not considered it. I had not considered it and I'm so relieved that I wrote a good exam. He said, "Well," he said, "And if you are, you must immediately begin studying Chinese." But at that time, Harvard did not teach spoken Chinese. They only taught classical written Chinese. And it was just about 10 people and they were all graduate students. So he said, "But here's what you do." He said, "If you go down to Yale,

They have a special program that they run there. They teach, they have a good program in spoken Chinese and they have it in the summer. And he said they run it because they have a contract with the Air Force and they're teaching Air Force recruits, these 18-year-old kids, how to speak Chinese so they can listen to Chinese Air Force traffic.

and monitor it. It was a three-hour drive from Cambridge to New Haven to go to Yale. So I spent the summer at Yale studying Chinese with Air Force recruits. And they were using a text that had been created by Yale. It's all about spoken Chinese. And that fall, when I came back to Harvard to start my junior year, decided to

go to the class on Chinese, but they were only teaching classical written Chinese. They wouldn't teach spoken Chinese. So I was very frustrated. But when my senior year, I applied for a Fulbright fellowship. And at the end of that year, I got to, when I graduated, I got to Taiwan. And interestingly enough, the program in Taiwan was run by Cornell University, but they were using the old Yale text, which I had started on at Yale.

And it was the best program for spoken Chinese. Yeah. Given your family history is so intertwined with the American history, with the great context of the world at the time, did you think of Asia much back then?

Really, almost nothing until I mentioned in my sophomore year, beginning in 1958, there were no courses offered at high school or college that I would have gone to. Even at Harvard, the Chinese history class was almost all graduate students at that point. When was this? 1958. The introductory class at Harvard that undergraduates could take, it was called an introduction class.

to the history of East Asia, which they were very careful to say it's China, Japan, and Southeast Asia. And it's probably equal attention to each of those three. And Harvard students had to give every course a nickname, and they called that course Rice Patties. Yeah, and that's the famous course by Fairbank and Reichauer. Reichauer. Yeah. Yes, and Reichauer taught, Fairbank taught some of it, Reichauer taught some of it.

And they had a couple of people talk about Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia got the least of it. What was it like studying with those two? Well, they were both very significant people. They were significant in every way. They already had important names. They were leaders of their field. Fairbank really helped start this field of Chinese history in the United States. And Reischauer certainly started the study of Japanese history.

And they had just, so my first year, they had just finished a textbook that was going to be used in their course, but it had not been published as a book yet. It was just a mimeograph form. So they gave us these big things. It was like you had to carry it around. It was like carrying one of those old store catalogs. There's hundreds of pages printed on one side, and you brought the thing into class. It was fantastic.

One volume was called East Asia is the Great Tradition, and one was called East Asia is the Great Transformation. It was a very good introduction. I mean, these were the leading American authorities on China and Japan, and they had a section on Southeast Asia. It's the first place I heard about Vietnam. It happened that year was the first year they were really offering the course, and then I had this conversation.

the texts. And what was John Fairbank like? Intimidating. He was a very tall man who was quite bald and he was always looking over his glasses at you. But he was charming and friendly. And if he sensed that you were interested in his field, he would do almost anything for you. He one time invited me to come up and visit him at his summer house in New Hampshire. Me and maybe one or two other graduate students

And we drove up and I was scared to death with him because he was this important figure. And I drove up, it was maybe a two-hour drive from Boston, and we ate breakfast, lunch, and dinner with him. He was this important Harvard professor. But he reached out to students in a way that few other faculty people do. And he had these regular gatherings at his house. And he had Thursday afternoon gatherings at his house, yes. And his house was right on the campus. It was a Harvard house.

They'd given it to him. And every Thursday afternoon, anybody who was in Cambridge that day who was interested in China was invited. So you never knew who you were going to meet. Actually, what was this house like inside itself? Well, it was an old colonial structure. It was a little yellow building. Harvard had grown up around it. It probably dated back to the 18th century. Is it the oldest house in Harvard? Yes. It's a little yellow structure.

wooden house right in the middle of the campus. Dunster Street and the street. I could find it easily. It's still there. Sure. And how was the interior like? He had a few paintings on the walls, but I don't remember. I only went there when he had other guests. It was also intimidating because

Whoever was there, Fairbank was kind of the social secretary. I mean, you'd walk in and he'd greet you by the handshake, and then he'd take you around to people, and he'd introduce you. He said, this is a famous professor so-and-so from Todai University. And here, now talk. And then he'd walk off and he'd go to the next person. And here you were speaking to this guy who only spoke Japanese, and I didn't speak Japanese. But he did that all the time with people.

But he was creating a field of Chinese history in the United States. It's really what he was doing. He was, what do we call him, an academic entrepreneur. He was creating this whole new thing, because Chinese history didn't exist as a subject for most people to study anywhere.

He was, I like to say he was a missionary for Chinese studies. My family history had very little to do with the interest in China. It was the experience of hearing Fairbank and then realizing there was this enormous subject that was very important and I didn't know anything about it and nobody else in the United States knew anything about it either. So this is a challenge. I always wanted to major in history. That was important. That was the subject that appealed to me and that I was best at.

I did some American history classes. I did an intellectual history class. The Chinese history class became the one that I was focused on. I couldn't tell you exactly why, but it was interesting to me. And the more I read, the more I liked it. After that first Fairbank class, then I signed up for the more intensive modern Chinese history. And whatever they had, I signed up for a Japanese history class. Who taught those? The modern history class was also Fairbank. The Japanese history class was Price-Hour.

Those were the only two, I guess, at the time. Those were the two at the time. And, of course, at the end of my senior year, John Kennedy named Roy Schauer as his ambassador to Tokyo. And on my way to Taiwan, I was a Fulbright, I stopped in Tokyo, and I knew two of Roy Schauer's grown children. And they took me around, and I got to see him in the American Embassy. Did you ever work in Japan, actually? I did. I took Japanese as a graduate student at Harvard.

For two years, it was intensive Japanese. For a variety of reasons, Japanese was much more difficult for me than Chinese was. And for some strange reason, perhaps because of the really good instruction I got at Yale to start with, Chinese wasn't that it came easily. I had to work at it, but it seemed normal to me. Even learning the tones, once I learned the tones, because most of the sounds in good Mandarin are in English.

with the exception of a couple like 许 and 西. Everything else is American English. And the grammar is so simple. It's subject, verb, object. And the tenses are kind of self-explained in the sentence. I go today, I go tomorrow, I go yesterday. In Japanese, it's just the opposite. It's a very complicated grammar. And it's very formal language. You have to know the status of the person you're talking to.

So you use different verb endings depending on if you're talking to somebody at a higher status, same status, or a lower status. And my mind doesn't work that way. Tenses are very important. Chinese is pretty straightforward and simple if you can do the tones. And I kind of liked it. Well, I guess you certainly have a talent for it.

But Japanese was, so I found Americans who started with Chinese, they always liked the Chinese people, started with Japanese, preferred the Japanese and not the other way around. Was Ezra Vogel working on Japan? Yes, Ezra Vogel, the first year I took class, the Rice Packing class, Ezra Vogel was taking it too. He hadn't yet decided he would be. Did you know each other back then? Yes, we sat next to each other. Oh, what do you think? He's a very nice man. I don't remember his name.

We were always sort of personally friends, even though he was a bit older and he became a professor. But there were several other older people who went on to teach about China, who I was, even though I was an undergraduate, I was sitting in the same classroom with them. There was a very nice woman named Dorothy Boer. You might have encountered her someplace. She's long since dead. She had white hair even then. And I can't remember, she was like from the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, but was taking these classes there.

When I first went to China, she was still involved with China. So that group of Americans studying about China at Harvard at that time, a lot of them went on to do things like Orville and me. Even just thinking now, right, to think that such a small class would produce so many talent for U.S.-China relations, U.S.-Japan relations.

I don't know whether it's a coincidence or whether it's the only place that you could do it. Well, that's true too. Well, there must have been something at Berkeley, something at Stanford. There were, but not to the same extent as Fairbairn. So Yale had Mary and Arthur Lord, but they were graduate students at Harvard with me, and they went on to have positions teaching, became full professors at Yale. They were somewhat older than I was, but they were there taking those same classes.

Mary and Arthur Lord. Those are the other two that I remember. And people like Andy Nathan and Perry Link. Oh, Andy Nathan. Yes, I certainly knew Andy Nathan. Perry Link I knew, but... Younger. How much was he? I don't think I knew Perry Link as an undergraduate. Andy Nathan I knew as a graduate student. Yeah, many major figures today were at Harvard with you. Because that was a place that Fairbank was a...

kind of evangelist, an evangelical figure. People gravitated towards him and he was preaching this new faith of Chinese studies. And after studying China for all those years, when did you actually start dealing with actual Chinese people? We're going back to when I first had anything to do with China. So obviously I'd been studying about China since I was an undergraduate and then a graduate student and lived in Taiwan. But my first real contact

with people from the mainland was in 1972. That time I was in Vietnam, but the New York Times got in touch with me and they said that the People's Daily wanted to send, this is long before normalization of relations, they said the People's Daily wanted to send journalists and reporters to the United States and have a tour.

And it means the Communist outlook on things. They assumed that the New York Times was the official publication. They thought you were the counterpart. They thought the New York Times was the, yes, was the People's Daily of America. So they asked the New York Times to arrange a tour of their correspondence in the United States. So the editor sent me

Cable explaining that and asked me to come back from the war in Vietnam to the U.S. to act as a guide. That's a significant undertaking. So I flew back from Saigon to New York where I met there were three men

And whether they were really correspondents for other people's daily or what, to this day, I don't know. They were ranking members of something. So I talked to them and we arranged a trip. And the New York Times provided a car and a driver. I was not driving. And where they wanted to go, they first got a tour of the New York Times. They saw various things in New York City.

I don't remember all of them. Then we went to Washington and then they wanted to see a farm, an American farm in Illinois, corn farm. A particular one? No, I negotiated with some agricultural organizations as to where to go. One of the things I remember, which was very striking, which is not political, but it's just difference between Chinese agriculture and American agriculture, was that they were astonished at how tall the corn was.

I think it was August. They say this corn is amazing. It was so much taller than Chinese corn. And then they had a question. They said, where is the irrigation? And the farmer said, irrigation? He said, irrigation? We don't need irrigation. We have rainfall. And in China, because rainfall is more erratic, the United States had more predictable weather patterns. They didn't have irrigation. And the Chinese kept asking me, where's the irrigation?

Again, not about politics at all, just the difference in natural conditions. But the farmer had tractors and he had trucks and he was doing all this work by himself with his family. Well, American farming is already mechanized. Yes. So that was all the way back in 1972. And then the thing they really wanted to see, they wanted to go to Detroit. And so we had arranged through...

Ford Motor Company to take them to a Ford automobile plant. And they were, again, stunned by the level of mechanization.

so few workers and so many machines. The United Auto Workers, which was a big union at the time, decided that they would invite the Chinese to stay with some auto workers at night. Three Chinese were sent to three different households. And they didn't like that because they wanted to be with each other. And the auto worker said, no, you can stay with me and you stay with us. And so there was almost a political crisis, whether they were

concerned about being separated from each other. They wanted to keep watching on each other or whether they were just uncomfortable being alone and being with American families. Could have been some of each. And the Americans were very hospitable and kept inviting the Chinese to eat their food. But of course, food was very different from what the Chinese were used to. So it was a very revealing trip to me. I'm sure to them too. To them. And they were the first people from the mainland to come directly into American households.

Did you ever stay in touch with any of them? For a while, but they didn't really want to stay in touch with me. And then Cultural Revolution came along and that. Who knows what happened? Wait, this is before Cultural Revolution? So this is 1972. Yeah, just before Nixon's visit. All these things were happening at once, the first steps to getting this. There were many little steps, which were the big steps.

But this was a little step. So that was one little thing that I had before I got to China itself. And now another thing, which is part of the normalization process, when Deng Xiaoping came to the United States in January and February of 1979, part of about the four years I was in Hong Kong, and Deng came at the invitation of President Jimmy Carter. And there was a large delegation that came, but the New York Times asked me to

come back from Hong Kong and be on that trip as much as I could see and report on it. So I got to go with the Chinese delegation. And they started in Washington where they met Jimmy Carter. Then they went to Atlanta.

which was always a little strange to me why they went to Atlanta. They wanted to see the American South. While Deng was there, they signed the first commercial agreement was with Coca-Cola to start importing Coca-Cola or start manufacturing Coke in China. I don't know what ever happened to that agreement, but Deng was meeting with the executives of Coca-Cola. Coca-Cola was very happy. Coca-Cola was very happy. It was unusual. And then, yes, we started in Washington, Atlanta, the agreement with Coke.

Then they went to Houston, Texas. They wanted to go to the Johnson Space Center there, where the rockets were being manufactured. The American space efforts were concentrated at that time in Houston. But some of the Houston Chamber of Commerce arranged some other things for the Chinese to do. And they took them to an American, a Texas rodeo. And the Texas rodeo

They had lots of American food. So there were baked beans and beef, enormous sides of beef. American hosts kept asking the Chinese to eat the beef. Chinese didn't know what to do with these enormous pieces of meat. And I said, the Chinese used to have their meat cut up very small. What they can't deal with is, look, I think the Chinese kept saying, this is very barbarian, such large pieces of beef.

Niu Rou shouldn't be. And they probably didn't know how to use knife and fork. They had learned some, but the baked beans and the beef was really, and coleslaw. It was very American, but it was not very Chinese. But then in some ways, to me, one of the most interesting scenes was the Houston professional football team had somehow, they had their cheerleaders there.

And there were these very tall American women with long blonde hair. And we were sticking out like this. And they had very short little skirts and high boots. And they kept coming over and holding the Chinese. And it was like the two cultures were not meeting very well. Oh, they were trying to meet. They were trying to meet, but...

The Chinese came to me and said, "No, please don't grab me." It was an interesting cultural misunderstanding. And you were there? I was there. I wrote a story in the New York Times about it. But it was, again, a reflection of the enormous gap at that point between China and the United States. That was not something that communists had prepared the Chinese for. No. Certainly not in front of their boss. Not in front of their boss, no.

And then the final stop on the trip was to go to Seattle because the Chinese were very interested in aircraft production. That's where Boeing is. Where Boeing is. In fact, ultimately, they signed a deal with Boeing to start manufacturing some Boeing planes in China, which was a big leap forward for China at that point. And they were really fascinated by the Boeing plants. Boeing had these just enormous manufacturing facilities.

That was, I'm sure, made a big impression on the Chinese delegation. And the Boeing people were very friendly because they wanted to sign a deal with China. Of course. Started with selling some Boeing planes. At that time, I think it would have been 707s, the first really successful commercial jetliner.

Did anyone on that trip leave an impression on you from China or even from America? The impression I have was how excited the Chinese were to be there, how happy the Americans were to see the Chinese, and then the enormous cultural gulfs between the two countries. Particularly, I think, because China was still very closed. Things were about to change. But the American businesses were certainly very excited. They were very excited. It was very goodwill. It was just the differences between the

The two countries and the two cultures were quite profound. And what did you think of Deng Xiaoping at the time? Did you ever meet Deng Xiaoping? I met Deng Xiaoping. On his trip. What was your impression? I met him a couple times. He's very short. He had a funny accent. He seemed, by comparison with other party leaders, he seemed quite moderate. He'd been, the things that he had to go through that he'd been, I forgot all the things that happened to him, but he had been, he himself had encountered a lot of trouble and

He was purged three times in his career. His son fell out of a window during Cultural Revolution and completely damaged his lower body. So he seemed to have realized that there were other ways of doing things, maybe better ways. He was not going to install an American political system. Probably not. No. But at that time, he seemed very moderate.

That's the best word. And with all the terrible things that he had seen happen. Did you meet other high officials, Zhao Ziyang, Hu Yaobang? Zhao Ziyang I met in Sichuan. I think it's in the book. Zhao Ziyang I met while he was still a party leader in Sichuan, before he was elevated. A number of times I was asked by Chinese, did I work for the CIA? And I would say, hell, I didn't. Oh, I met Zhao in Sichuan in 1980.

And I went to Sichuan to see the industrial and agricultural reforms that Zhao had introduced in Sichuan, giving factories more autonomy, giving the peasants a greater say over what they planted. Oh, that's right. Zhao came to the hotel where I was staying. Yeah, I remember reading that somewhere. He agreed to the interview, and he arrived by himself. That was stunning. He didn't have his guards, handlers. He just walked in, which is so unusual.

It's on page 300. I forgot what happened to him. After the tournament, he was basically locked up in his own room, put under the home detention for the rest of his life. He died like 10 years ago. Oh, yeah. Now I know he was no longer alive. Yeah.

But when he was the party leader in Sichuan, he attempted some really forward-looking reforms. It's starting to be a new China. I mean, an awful lot of the people that I knew were very worried that the Cultural Revolution was still going on. They weren't sure. And people still did get arrested for it.

The door was opening, but a little light was coming in. Something, but the question I had always was, we're beginning to see these economic changes, but are we going to have political changes? Political change is going to go as far as the economic changes. Is it going to be as much moderation or liberalization? I never was sure that that would happen. And how did you feel when China attacked Vietnam, given your time in Vietnam? That was a surprise.

The Vietnamese were surprised. That was a strange episode. I don't remember the details of it, but it was bizarre. The Vietnamese are really a Chinese people. The very word for Vietnam, Vietnam, is their pronunciation of Vietnam. But Vietnamese, the pronunciation is very different. Mandarin has four tones and Vietnamese has nine tones. It's a much more difficult language for foreigners than Mandarin is.

lots of strange sounds which don't exist in English. That's something I find quite puzzling, is because there is a whole generation of Americans coming out of the Vietnam War and quite anti-Vietnam War. But when Deng Xiaoping invaded Vietnam, there was very little resistance from the American side. Carter didn't seem to care, and Mike Oxenberg didn't seem to care so much.

And the China scholars who were completely anti-Vietnam War didn't seem to put up a protest against Deng Xiaoping or anything. Yes, I remember that. In some ways, that's an interesting question. So when Russia invades Ukraine, we do care. That would be the closest parallel I can think of. And I presume now with China invades Taiwan, you would care. Oh, yes, that's something different.

Somehow, poor little Vietnam. Poor little Vietnam. I think Americans were so tired of the Vietnam War, they just couldn't express outrage anymore about Vietnam. And the communist government of Vietnam won that war. So cynically, I would say that some people were happy to see them getting whacked a little bit. But that's a good question. There wasn't much of a debate about it in the United States. So I don't know. There were some people who wanted to protest, but

American public opinion just didn't seem to care. I think we had a case of, I would call it, Vietnam exhaustion. We don't want to hear anything more about Vietnam. We don't want to worry about Vietnam anymore. But I'm very happy to see now that Americans are now interested in Vietnam again in a positive way. But it's taking a long time because next year is the 50th anniversary of the end of the war in Vietnam. And I think that it's interesting in the sense that I remember you writing somewhere that

Some Americans suspend their critical lens when it comes to China. Yes. It's very usual to be suspicious of what the Soviet Union is doing, quite critical of their political institution, domestic affairs, international ambition. But when it comes to China, then American observers tend to have a certain wishful thinking, optimism, faith in the goodwill. I think you're absolutely right. If we broaden the lens a little bit here,

So I think with China until after 1949, we thought, Americans thought, I should say, that the communists were terrible, Mao was evil, all these things were bad. And we went to war with China soon after that in 1951 in Korea.

So people were very anti-China because of those things. And then when we began reestablishing normal relations with China and Americans could go to China and American businesses could go to China, then we changed again. But we totally flipped it upside down. And everything about China is good. Some of those same things happen with Vietnam in a different way. But we didn't see the messy part or the complications. What's your take on that? Why does this happen? Why can't the public understand?

sentiment swing in the complete extremes. Well, it's like cheering for a football team. You get all excited about your team and then something happens and you may end up cheering for the other team at some point. For the case of China, is it just because businesses couldn't make money? No, it's not just, it's not as simple as that. That's a factor.

Americans always had probably a very oversimplified view of China. The American missionaries went and came back and told their stories. We didn't have a very sophisticated view of China. I'm not sure what Chinese thought about the United States, but... Probably not very sophisticated either. They thought NYT was part of CIA. That's the understanding of America. During World War II, we were the Chinese nationals were on our side. We thought John Kayshek was good, but it turned out no, that was not right.

And then the Chinese nationalists went to Taiwan and were nasty to the Taiwanese, but now Taiwan has gone pretty well. So things are more complex than most of us think. There's a saying that Soviet scholars hate Russia and China scholars love China. That's true. Although I think Soviet scholars in some ways, they probably like Russia more than they admit. China is a big complex country.

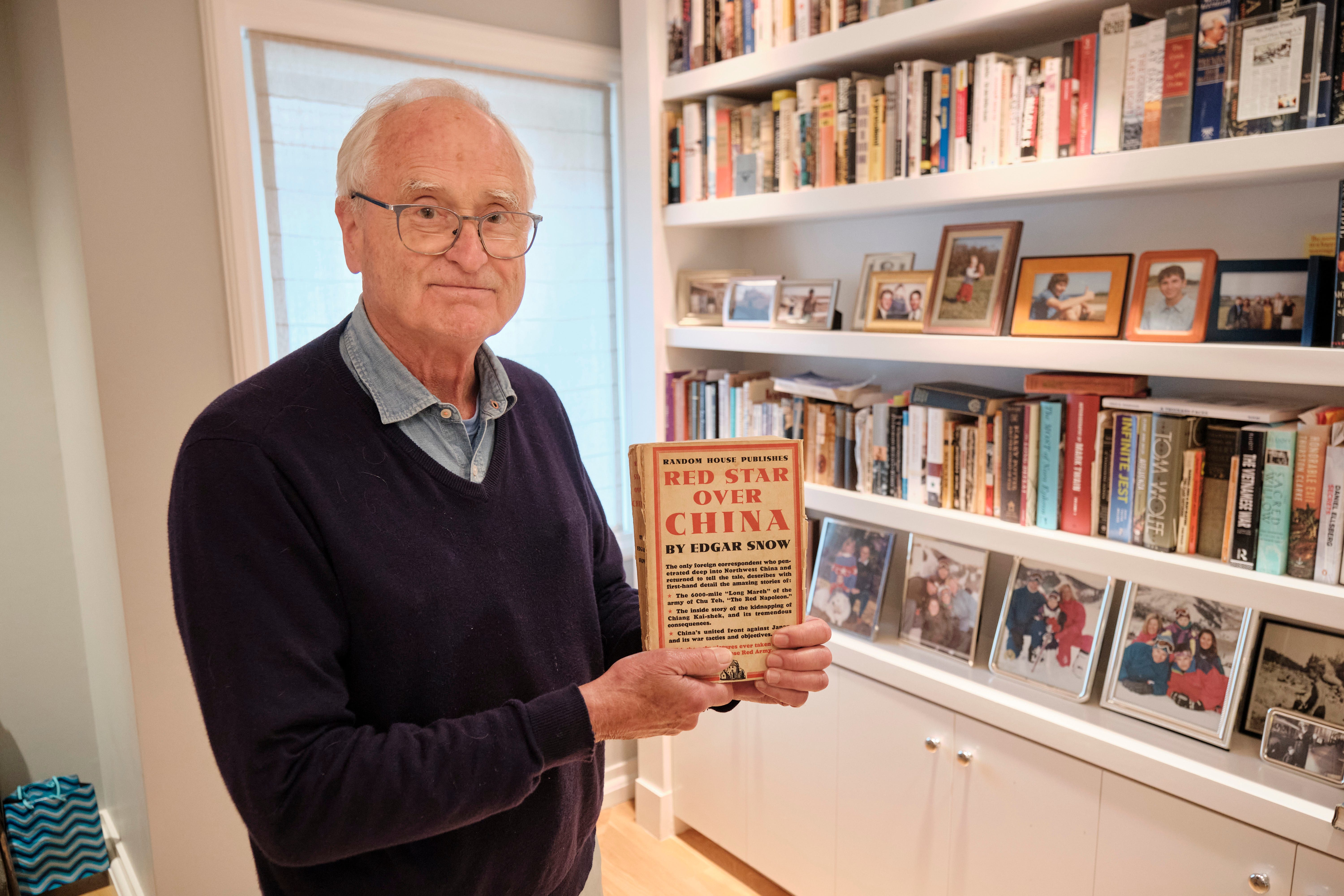

So one of the most influential books for me was the Edgar Snow book, Red Star Over China. So that, in its way, has its own romantic view of China. We were on the Long March and the poor communists are doing well. Against all odds. Against all odds. Against the corrupt, capitalist, nationalist government. There's a wonderful book, which was very influential for me, called Two Kinds of Time. Have you ever seen that or read that?

That was written during World War II by a man named Graham Peck, P-E-C-K. I highly recommend it. It's going to seem very dated now, but when I read it, when I first started studying about China, I was stunned. It's a much more sophisticated take on China than Red Star or China, written basically at the same time. He was in China for a long time. And he does talk about, he says two kinds of time. He looks at two very different ways of looking at China.

It's a big fat book, really interesting. Those are very nice little details that tell us how the relations normalized and how it became okay for Americans to wander around China. One of those big steps would be opening the NYT Beijing Bureau and becoming the first NYT correspondent in China. Could you tell us that story? How did it all happen?

Here again, it's almost 50 years, so my memory is a little blank on that. What the exact agreement was between the two governments, I've forgotten. They would admit a certain number of American news organizations in the United States would permit a certain number of Chinese journalists to come. I just don't remember the details. And then when I got to Beijing, so initially it was the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Associated Press,

and maybe the Los Angeles Times, I forgot. And then pretty quickly, then a couple of the television networks, NBC and CBS, I don't remember, but they were slightly different category. But it was pretty limited. I was like four or five. And later on, it expanded, but initial group. And the United States, they accredited the New China News Agency and Raymond Ribal, and I've forgotten who else.

But I had to go to the foreign ministry, the information department, and get my credentials. And at first, I couldn't file stories, but fairly quickly, we were able to send stories. There was a lot of bureaucracy, but honestly, I don't remember. If I tried to tell you in detail, I would be wrong. Were you excited to go to China? Oh, of course. Yes. In some ways, I've been trying to do that for decades.

many years. Certainly from sometime in the late 60s, I was hoping to do that. From the time I became a journalist in 1969. But honestly, it's too long ago to remember the exact step. Do you remember the feelings that when you finally arrived in Beijing, opening a new office? I mean, where was your office? China had a real shortage of office space for foreigners of any kind. There was a shortage of housing space for Chinese, most of all.

and there were a shortage of offices, they weren't prepared to have an influx of foreigners coming in, businessmen. For me, for the first year I was there, I lived in a hotel room in the Beijing Fandang. That's what they gave me, and the Washington Post had the same thing. The Washington Post correspondent was married to the Los Angeles Times correspondent, so they had two hotel rooms. Oh, this is the Matthews. This is the Matthews. And they had some small children. At some point, the Christian Science Monitor was allowed to send somebody. I don't think that was at first.

I had the one hotel room, I think it was on the third floor of the Beijing Fandian. That was my office, my living space and everything else. But I couldn't feel sorry for myself because most Chinese didn't have room nearly that nice. But Peking Hotel was the best hotel. It was, but there weren't very many hotels at that point. How was Peking Hotel like actually back then? It was comfortable. It was crowded.

the people in it were all, people were not there for just one or two or three nights. Most people were actually living there. It's almost like an apartment. It was almost like an apartment, but downstairs there was a restaurant or a couple of restaurants, and it very quickly became evident that the people who operated the elevators, because they were still elevator operators then, they were probably sent by the Ministry of Public Security. They were keeping track of whoever came in and came out, and there were

probably people from the Ministry of Public Security at the front door, asked any Chinese who tried to come in had to show their credentials. I would occasionally try to bring in a Chinese guest, but they would be stopped downstairs. And it was awkward. If the Chinese visitor was not afraid of being found out, they would come in. But if they were worried about being discovered, they wouldn't come in. So I really couldn't meet people at my office. At the hotel. I had to go somewhere else. Often it was going out to parks.

or sometimes to restaurants, because Chinese going out to restaurants, so that was okay. So there was a constant, I'd say there's a battle of wits trying to, I can't say fool the Ministry of Public Security, but to at least try to meet ordinary people or important people without being reported back. And I felt almost all the time that I was being watched in some way, shape, or form. And I think there's at least one anecdote in the book

So I had a Chinese assistant, and I'm sure that he was supplied by the Information Department of the Foreign Ministry, but I'm sure he was reporting to somebody in public security. I came to think that he was probably reporting. Once a week, my Chinese friend said he would have to make a report on me regularly. And one time, he was out for lunch, and there was a phone call, and I answered in Chinese, and they asked for him, and I said, he's not here.

And they said, tell him when he comes back, he doesn't have to make his report on the foreigner today. And that actually happened several times. So I said, OK, I'll tell him. I was being watched, as were other correspondents. I think since the New York Times was sort of part of the American government, that I was a more interesting target to watch.

And how was the newsroom like? Your office was essentially your apartment, right? My office was my hotel room, was my office and my apartment. It was in one room. How did you write stories? I had a typewriter. Do you remember typewriters? I've never used one. I've seen them in museums. At that time, I had to go to the telegraph office to send my stories. The telegraph office in the hotel? No, the telegraph office on Main Avenue. I'd have to drive there.

And they'd give my copy to the, I was typing it out and then I would take it to the telegraph office. The telegraph office would send it but gave them a chance to read it before I sent it. Yeah, they have an advanced copy of everything you write. So it was like living in a fishbowl. I was being examined all the time. And how do you work with editors in New York? They're so far away. It's a 12-hour time difference.

And it's easy to remember because it's the exact opposite. If it's 6 p.m. in Beijing and I'm finished for the day and sending my story, then it's 6 a.m. in New York. My editors are not yet at work. And in those days, you paid for telegrams by the word. So they were always asking us, don't write too much in some ways, save money. But we were able to communicate. And at some point there, I was able to make phone calls, Trans-Pacific phone calls. But you had to

At that time, you had to book a call in advance. You had to reserve the call before you made it. So you couldn't just pick up the phones down in New York. And what kind of stories were you looking for, looking to report? And did the editors have an idea of what they wanted you to write about? In my own mind, there was a division between news stories. If there was something political that China was going on or something between the United States and China, I had to write about that.

those sort of more traditional news stories and developments, or if they were releasing an economic report about production or some kind of commercial agreement that these Pan American airlines have been given permission to now make flights to China, things like that. But the stories that I was really more interested personally were the stories about daily life, what life was like for Chinese and how the Chinese society really worked at that time, which is reflected in the book.

Those kinds of things is what I was looking for. Just before I got allowed into China, I had signed a contract to write a book about China. And I knew it was competitive because the Washington Post correspondent, the LA Times correspondent, had also signed a contract to write a book. So the kinds of stories that I thought would go into a book were, I was particularly interested. Almost always there were things that I had written about for the Daily Paper well before. I was able to write in more detail in the book.

Because the news story, you're writing 600 or 700 words. Actually, how did you write a book while also writing all those news articles? Oh, I didn't write the book. I wrote the book after I left Beijing. I couldn't write the book there. It was impossible. There was no time. Yeah, because you were writing like two pieces each week and chasing the beat all the time. When I left China, I actually came back to the United States. I came back to Boston, and I bought a house in a suburb.

And I had an office in the basement, and I sat there from early in the morning to late at night. I could not do that while I was in China. I was coming up with ideas and material, but nothing that's written in the book was written until I got back to the U.S. It was a very busy job in Beijing to do the daily reporting. What's your drill? What's a typical day like for you? Every day is a little bit different. Sometimes I would just go out on the street and walk.

Sometimes I would go to restaurants. I'd go into stores. Some of the best things for me, it was unexpected, whether on a train. And train travel was the really best way to get around China at that time. There were not that many airplane flights. So if you got on a train, people often would sit down next to you and I would start talking to them. And I knew for them it was taking a risk. And some of the people I was able to talk to had actually

had gone to the United States as students and had learned good English and were comfortable with Americans but hadn't talked to an American in 25 or 30 years. And they were, in some ways, they were very happy to talk, but they knew they were taking a risk. They had things they wanted to say, they wanted to talk about what had happened since the communists took over. There was a story in your book where there was a woman who wanted to talk to you not too far from Peking Hotel.

I think it was late night at night and then got pulled away by the police and they just said they're not allowed to talk to foreigners at night. Yeah, those things happen, you know. And I was very happy that when people would talk to me, I would always worry about what was going to happen to them. And I did hear back later that some people were picked up by the police and got demotions. I don't remember the details, you know. One senior person that I met was Sun Yat-sen's widow.

and she had a very almost a palace for a house and she was very hospitable to me and I was able to meet other people in her family and I met a number of men or women whose fathers were generals in the People's Liberation Army and they were willing to talk to me but it didn't meet their parents. To what extent members of the party or the People's Liberation Army learned about the United States through the from their children who had contact with foreigners because it would have been

too dangerous to them or too damaging to them to have those contacts themselves. Probably some of them did. And then later on, the children would get jobs. Not at my time, but later on, they got jobs with American companies and they could make some money out of it. They could come to the United States and be trained in whatever it was. That hadn't yet happened. Those kinds of deals were a few years away. The question that I have that I don't know the answer to is, after I left

1981, what the changes that China has gone through since then. I went back eight years later in the late 80s, 89, after the killings in Tiananmen Square. Business, American business, foreign business was already there. But how that's shaped the lives of party leaders, I have no idea. Maybe they forgot about me. No, I just, it really was based on the difficulties I had even then and being told I was very fanhua and

And in the book, it was like the book was, to use the book metaphor, it was like closing a chapter. China was a chapter and I should go on and do something else. With that...

This is the end of this episode and hope you enjoy this one jointly brought to you by Peking Hotel and China Books Review, a digital magazine publishing commentary on all things China and bookish. If you like this episode, maybe you wish to subscribe to our Peking Hotel Substack channel and follow us wherever you get your podcasts. It's been a pleasure speaking with you today and I'll talk to you next time.