Chapters

Shownotes Transcript

WNYC Studios is supported by Zuckerman Spader. Through nearly five decades of taking on high-stakes legal matters, Zuckerman Spader is recognized nationally as a premier litigation and investigations firm. Their lawyers routinely represent individuals, organizations, and law firms in business disputes, government, and internal investigations and at trial. When the lawyer you choose matters most. Online at Zuckerman.com.

Radio Lab is supported by Progressive Insurance. Whether you love true crime or comedy, celebrity interviews or news, you call the shots on what's in your podcast queue. And guess what? Now you can call the shots on your auto insurance too with the Name Your Price tool from Progressive. It works just the way it sounds. You tell Progressive how much you want to pay for car insurance and they'll show you coverage options that fit your budget.

Get your quote today at Progressive.com to join the over 28 million drivers who trust Progressive. Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and Affiliates. Price and coverage match limited by state law. Ever dream of a three-row SUV where everything for every passenger feels just right? Introducing the all-new Infiniti QX80 with available features like biometric cooling, electronic air suspension, and segment-first individual audio that isolates sound.

Right to the driver's seat. Discover every just right feature in the all new QX80 at infinityusa.com. 2025 QX80 is not yet available for purchase. Expected availability summer 2024. Individual audio cannot buffer all interior sounds. The owner's manual for details. Every sandwich has bread. Every burger has a bun. But these warm, golden, smooth steamed buns? These are special. Reserved for the very best. The Filet-O-Fish. And you. You can have them too.

For a limited time, the classic filet of fish you love is joining your McDonald's favorites on the two for $3.99 menu. Limited time only. Price and participation may vary. Cannot be combined with any other offer. Single item at regular price. Listener supported. WNYC Studios.

Welcome to our HR exit interview. Welcome to the HR exit interview. This is so silly. All your answers will be purely confidential, except for the ones that we're going to broadcast to millions of people. Yes. Yeah, this is very, very bad HR practices. Hey, everyone. This is Lulu. And Latif. Okay, number five, it says here on our official questionnaire. And today, what was your favorite bathroom to use for number two?

Oh, I can tell you. We are talking to Radiolab producer Rachel Cusick. That's me. In the actual physical live studio. In the physical studio. Yes. Rach has been a producer on the show for six years. Very uneventful six years. Totally normal six years. Yeah, nothing happened. She has made... I think of you... I mean, you worked on the G series. You did The Queen of Dying, which totally blows up grief and...

these kind of emotionally intense stories, but you've also done some of the dumbest. Like, what? What? Airplane farts. What if the earth was made of blueberries? I contain multitudes. Thank you very much. You do. And we have brought you in here because we're going to play

one of your all-time bangers. And I think it was the first episode that you really, like, it was a full episode that you'd done. Yeah, it was the first one where I was like, here's this little nugget and let's, like, spend a whole hour staring at this nugget. And then the whole team then

made like the chicken nugget pack, you know? And this episode is called what? Cataclysm Sentence. And we're doing this one today because it's great, but also because we are... We're suffering our own cataclysm over here. Yeah. Which is that Rachel is leaving us. Leaving all of us. You too, listener. Yeah. I know. I know. I'm leaving my grandma. I'm leaving a lot of people right now. But I myself am feeling my cataclysm of losing you guys and leaving the show behind.

Stepping out into new things that I don't even know what is waiting for me, but mostly moving geographically across the other side of the world. To? Australia. Australia. Yeah. Where that's going to be really annoying to everybody who actually lives there. So in just a quick little, before we play this episode, I'm going to ask you a question.

Can you just talk a little bit about how it came to be and like what happened? Yeah. So in the beginning of the episode, you'll hear like exactly why I bumped into the idea. But basically, I ran into this question that then I brought to a meeting. And I was just like, I don't know what it is about this, but I need us to think about it. And I was just like, I want to

get this question asked to as many people as we can. And for some reason, the whole team decided, let's throw all of our love and attention into this. And everybody is going to take a little corner of it. They're going to follow it into their deepest heart's content and call up the people they admire. Everybody rallied around it, like dozens of phone calls over months. It just felt like the

the scene at the end of the movie where you get, like, lifted up. It's like, yeah, let's carry this through all the way. And then it was, like, a whole year-long thing. And then it came out in 2020. So, like, early days of the pandemic. Well, should we take a listen? Yeah. And then maybe we'll ask you one thing at the very end. Yeah, let's do it. All right, so here we go. Cataclysm sentence from 2020. Ah!

Before we begin, just want to let you know this episode contains a couple moments of explicit language.

All right. Hello. Okay, so this episode took the entire staff to put together, but it really began with one of our producers.

Rachel Cusick. You just have been named Rachel Cusick? Not much. Just stretching, watching you eat a sandwich. I'm sorry. Living life. Living life. All right. Cool. All right, now that I've made a mess of my sitting area. So how did you—maybe take me back to the moment you—how did you bump into this? Okay, so I bumped into this idea because of this book that is in my hand right now. It's called Eating the Sun. Okay.

And basically, I got pulled into this book because I was like, okay, eating. Eating. That's pretty much all I need. Just have like that title in anything. And I'm like, I'm sold. Send me a copy. You are the foodiest among us. I am the foodiest. I love food so much. And so I thought this was going to be about food. And this book comes and each page is a different musing on science. Wonky wonky. But I'll just read a few. Planetary motion. What is heat? Milky solar galaxy system. So they're all kind of like university reflections. Yeah.

Anyway, pretty early on, I'm flipping these pages and on like page 17, I come across this thing with Richard Feynman and this prompt that he gave in this lecture series back in the 1960s. And I was like, wow, that is perhaps the like coolest question I've ever seen this year.

Okay. Ready? Ready? Hold on. Hold on. Wait, wait, wait. Before you do that, maybe just set up like who Richard Feynman is. Okay. So Richard Feynman, this famous physicist. At the time, he was like a whippersnapper of Caltech. I imagine there was like a soundtrack. It's like, stay in love, stay in love. Every time he like walked onto campus, he was like the hotshot. He was pretty attractive, too. He was? He was a handsome guy?

handsome guy like slicked back hair so he was famous he had not yet won the Nobel Prize but he was like on his way to do it he had just worked on the atomic bomb everyone kind of knew who he was and

But at the same time he was exploding on Caltech's campus, Caltech was having a problem because physics was so boring at the time. Like they could not get anyone to like come into an introductory physics class and get excited about it. So they tapped Richard Feynman to redo the physics curriculum for physics 101. And so he was like, fine, I'll do it once. But like, that's it. You like take notes because I'm done after this. And so he just like took at redefining what physics should be as an introductory thing.

So I actually went and found audio of this lecture. Oh, I think I've actually seen photos of this. Black and white, he's at the front of a classroom in front of a chalkboard. For two years, I'm going to lecture you on physics. I'm going to lecture from a point of view that you are all going to be physicists. It's not the case, of course, but that's what every professor in every subject does.

So assuming that you're going to be physicists, we're going to have a lot to study. Now, typically, the way that physics 101 used to be taught... There's 200 years of the most rapidly developing batch of knowledge that there is. People spent like an entire semester of physics learning about like the history of physics. There's so much, in fact, that you might think that you can't learn all of it in four years.

And you can't. You have to go to graduate school, too. They didn't learn anything kind of like poetic? Mm-hmm. So Feynman, before he launches into his lecture, he's like, Well, what should we teach first if we're going to teach? Look, I could teach you about the history of these equations and the formulas. And then just showing how they work in all the various circumstances. But he doesn't. Instead, Feynman opens his entire lecture The first lecture. with this question. If in some cataclysm,

All of the scientific knowledge is to be destroyed, but only one sentence is to be passed on to the next generations of creatures. What would be the best thing, the thing that contains the most information in the least number of words?

So that is the question. So if the world ends and all information is gone. But we can only pass on one sentence to the next generation. There's a little scrap of paper fluttering in the post-apocalyptic breeze. Yes, but it has to be the least amount of words with the most amount of information. So I can't give you like a textbook, you know? It has to be one thing that's concise.

and can unlock the universe. Like, what would you write on the paper? Well, yeah. What would you do to, like, pass the baton to the next generation with the simplest thing that you could possibly think of? Oh, that's an interesting question. Did Feynman in that lecture have an answer? Yes. He said, I believe it is the atomic hypothesis. It is the atomic hypothesis, or the atomic fact, or whatever you want to call it. That hypothesis

All things are made out of atoms, little particles that move around or in perpetual motion

Period. So this is his sentence that would be on the paper fluttering in the breeze? Yes. That would land in the hand of a little alien child and he would expect that to be the thing that they use to restart their civilization? Yes, which if you are like that little child, you're like, what the hell am I supposed to do with this piece of paper? So what? I just want to know how to build a fire, you know? But...

The thing that I love about Feynman's answer is that once you begin to pick it apart, it just begins to grow. You'll see. And grow. There's an enormous amount of information about the world if just a little imagination and thinking is applied. I've talked to a lot of physicists this week to understand what the hell the atomic hypothesis is. Okay. Come with me. Yeah, please. Okay. So let's just take it part by part.

First part. Like, computer everything. The coffee slash seltzer slash sandwich that you're just spilling. Yeah, you are atoms. Atoms are the ingredients. That's part one.

Part two. Atoms. Atoms are all moving all the time. They're continuous jiggling and bouncing, turning and twisting around one another. That's really important because once you start to figure out that atoms are in motion, you begin to figure out things like... Let's look at heat. Temperature. With an atomic eye, so to speak.

There's also pressure. Electricity is a source of energy. Electricity. All these things have to do with how fast atoms are moving, how many atoms are moving, what parts of atoms are moving. So from there, you're like a hop and a skip away from like... The power of these. Steam engines. Telephones. The electrical grid. Gasius pressure drives this plane forward. Understanding flight. Good evening. We had a high... Weather patterns. Barometric pressure 30.04. It's steady.

So that's part two. Okay. Part one tells you what matter is. Part two tells you basic things about that matter. Part three... Atoms attract each other in some distance apart, but we pair being squeezed into one another. ...is basically how atoms interact with each other. And once you understand that, it is huge. Because in this last part is basically all of chemistry.

Once you start understanding how atoms come together to make molecules, you can start putting molecules together to make things like antibiotics, vaccines. You can build things like a combustion engine, batteries, all sorts of plastics, rubbers, tires, sneakers, concrete. But also commodities.

Balloons. Or. The essence of life. You can start to understand things like proteins. Amino acids. Fatty acids. Carbohydrates. Vitamins. DNA. To me, like, this is what makes the sentence so cool. Because everything is in there. Everything you need to know about the natural world and how to manipulate it. But do you feel like. Oh, sorry. Also chocolate chip cookies. Yeah.

Think about a world without chocolate chip cookies. You would not know. Is there anything else? Chocolate chip cookies were the big finale. I don't think you really responded properly, but that was the finale. Well, you know what? I'm going to take your chocolate chip cookie inspiration and follow it. Okay, great. Because what is a chocolate chip cookie? It is flavor, which I'm sure we could sort of reduce to –

Nothing but the sparking of electrons on a certain membrane in the tongue or something. But really what chocolate chip cookies are, I hope you'll agree, is that momentary ecstatic feeling you feel and the sense of joy and well-being and then the subsequent crash, right? Yes. So all of these things are, do you feel like they are reducible to atoms? Yes. Do you feel like love? Yes.

is explained by the atomic hypothesis? Do you feel like the complexities of human interactions? No. Morality?

No. That is where it falls short. Everything that's physical in our world can be described by atoms, but like music. Like you can't look at the atomic hypothesis and create like Mozart. Right. Or you can't like learn how to be a good partner with the atomic hypothesis, you know? Right. Like there are these big gaps that you just are missing. I think that and thus a door opens. Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Don't you want to hear? Yeah.

Don't you want to hear the musician answer, do Feynman's exercise? I suddenly want to hear who's the sort of great philosopher of chocolate chip cookies. And so. Dun, dun, dun. Cue music. What's the music for a cataclysm? I don't know. I mean, it's. Is it really loud or is it like a little like dust bowl and it's quiet, you know? I think it starts small, like a, like a tone. And then it, then it's two tones and then it's more and then it gets bigger and bigger and bigger and then it expands and.

Feels kind of primal, but also hopeful, maybe? I don't know. As you were talking, that did remind me of a thought that I had when I came across this in the very first place. Because it does, when I, I think I came across it like a year ago when I was feeling like everyone, like the political conversation was just especially, what's the word when you think like the sky is falling? Like chicken little-esque, where it's like everything is falling apart. Like everything. Apocalyptic. Yes. It felt like everyone felt doomed.

And I was like, if the world actually was falling apart around us, what would be the only thing that we have to show for it? Like, what is a way to bring what Feynman thought back in the 60s

And bring it to today when it does kind of feel like everyone thinks the sky is falling. Yeah. I should say quickly that the two of us had this conversation many months ago back when the world was a very different place. How does it resonate? I mean, tell me a little bit more how it resonates with you personally. I mean, this is coming from a place that I think I'm like pretty lucky to have this thought because I'm definitely like very lucky in a lot of ways. But like I think I'm just like a hopeful person. And I often like...

love spending time with older people in my family and like feeling like before they go, I need to get like whatever wisdom they have because like once they're gone, it's gone, you know? And so when I think about that, I'm like, I just want to like pull all the goodness out before like something goes wrong and preserve it. Who are you talking about? Whose brains for you personally are you trying to do that with? I mean, I think about it. I was talking to my friend. They're like, why do you only hang out with old people? Because I was just like,

I think most people, even because I'm 24, but someone who's 30, I think they have seen more of the world than I have. And I would rather spend time with someone who's... Oh my God, your 24-year-old friends are talking about 30-year-olds as if they're old people? Well, I mean, a lot of my young friends don't want to look towards older people because they think this is a mess and we are the future and we need to do this. And I totally agree with that in a lot of ways. But I also think...

Why start from scratch if there could be something pulled out of the dumpster that might be helpful? And so my grandma, my grandma and I, she's the most important person to me in the world. So that's one person. But every, like you or Robert or old people. Old people, thanks. That's fine. I will take on that moniker. What do you, I mean, none of my business, but I'm suddenly curious to know, what kinds of questions...

Do you sit with your grandma and you ask her just general questions or do you have more specific things you wonder about with someone of her age? Well, it's like pretty specific. So my mom died when I was six. And so like one thing that seems to motivate I think a lot of that curiosity is like,

My older siblings, I was the youngest of five who lost her. And they all have these like very concrete memories that like when I think about it, it's like I arrived on the scene right after she left the scene.

Like when my memory finally started to kick in, it's like right when she left. Do you remember anything about her? There are a few memories that I know for sure are mine. And then after those few, like I think on one hand, I can count ones that I know are mine. And so a lot of the times when they talk about these things, like...

these birthday parties that she used to throw or like her laugh or the like music she'd play in the minivan. I like, I don't actually remember any of those things for myself.

I mean, how do you fill that then? Do you talk to your, do you try and just ply anecdotes from your older siblings? I don't know. Like some, some of it, I feel like a little sad that I have to ask for those things. And so sometimes I just like hang back and let them talk. And then I feel a little bit jealous, but then I also do go searching for them. Like sometimes with my grandma, like my, I call my grandma once a week.

And like she told me this one story the other day that I just thought was so funny. Like it was this like sense of humor of my mom that I like didn't even know existed. And that just felt so it was just like meeting a different side of her that I had no idea was there. But it was just this like little angle of like a diamond gem, you know, like there's some little surface that like I just felt my thumb go over and I never knew it was there.

And like, I don't know, I just kind of want to feel all the textures and like memories of people because I know how easily they just go away. I think I like walk through the world collecting things like I'm like a little stick collector. Like I want to collect all the sticks I can because I know what it feels like to feel like empty handed. So what began as that conversation with Rachel about the cataclysm sentence, what could you

What's the simplest thing you could pass forward for the next person to hold on to? Well, what happened is that really as a staff, we got interested in that idea. Kind of got fixated on it, actually. And so what we did... We started calling people. Hello? Hello, is this Mr. Nick Baker? This is indeed. Hang on one second. Hello, hello, can you hear me? Yes, I can hear you. And dozens of people. Hello, Meryl? Yeah. Hello?

Artists, writers, philosophers, historians, chefs, musicians. So I sent you an email. And we asked them. That asked you a question. Feynman's question. If hypothetically the world were to end and everything was lost, all our knowledge gone, what would be the most important information in the least amount of words that you would convey to the next set of people? What would be your sentence?

We're going to play you a bunch of the answers that we got. We can't play all of them because that would take four hours. So we're just going to play you a selection. And that's coming up right after this break. Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad. This is Radiolab. And today we are answering one question. If the world ends tomorrow, what would be the one sentence you would leave for the next generation of humans or creatures or aliens or whoever comes next? What would be your cataclysm sentence today?

We'd pass on the most amount of wisdom in the fewest number of words. We asked this question to a bunch of artists and writers and scientists, all sorts of people. We got all sorts of answers. We're going to play you a selection of those answers now, starting with... For me, it's something like, you will die, and that's the most important thing. ♪

Writer, mortician, Caitlin Doughty. And I think most people get that. I think most people get that they're going to die. But I don't think what most people get is that the fact that they're going to die is the most important thing that will ever happen to them. Humans are one of the few creatures that understand death.

and understand, live their whole lives with the knowledge of their deaths. And so it's this conflict within us. We live in these shitty decaying bodies, but we feel so special and we feel so important. So how do you reconcile those two things? It's hard to reconcile them, so you have to create. You have to transcend. You have to have religion. You have to have communities. You have to have art.

Those are created by our fear and our strange, difficult, weird relationship with death. Okay. Oh, so let's talk about fear. Esperanza Spalding, musician and wolf enthusiast. Okay, here we go. Here's your parallel from the ecosystem. When wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone Park,

At first, the thinking was we're just doing this because we don't fully understand yet all the ways that this species is important, but we know that it is and it's been absent and we finally have this opportunity to reintroduce them into Yellowstone. So, of course, all the biologists are studying this like crazy conservation biologists. And the first thing that happened was all the game who hadn't been subjected to any threats. They were they were the top of the food chain. All of a sudden, they all became more alert.

and more responsive. And they stopped grazing constantly in the exact same part of the river. They had to move more because now there was this like threat of the wolf. So what happened is they start moving more. They start grazing higher up in the hills where they're less likely to be just, you know, picked off in these low grasslands.

So what happens is the banks of the river get firmer, which means the flow of the river becomes stronger, which means beavers can come in and start to build their dams. Also, because the game is not grazing in the same area, trees that...

previously had been chewed up in their early sapling stages start growing. So songbirds return. All these species of bird come back into Yellowstone that had been absent because they didn't have the right canopy cover. And because the beavers come in, that creates more pocket environments for other animals and that brings in more big predators who are eating what the beavers are attracting. So basically...

This one species who had become dominant and very comfortable and at the top of their food chain, just the presence of them having to confront regularly and respond creatively to a little fear completely changed the health and the landscape and the sustainability of the ecosystem. So maybe it's like...

Maybe it's like just that, the willingness to respond creatively to fear without trying to eradicate the source of the fear.

My name is Cord Jefferson, and I'm a television writer and producer. Okay. I wrote down a bunch of different things that I then erased, and then I sort of settled on one that I thought was definitely going to be my thing, which was about race and racism. And I had that sentence all prepared, which was, race isn't real unless you make it real, at which point it will become the biggest problem in the whole world. And then I started thinking that, you know,

what's sort of even bigger than racism? And to me, like even bigger than racism is just general fear. And my personal history is that my mother is a white woman who married my father, who's a black man, and they disowned her. And so I never met my grandparents. I would send them letters

letters, which they would return. And I until I stopped sending them when I was I think I was about 10 or 11. And I just and I and I saw how much that devastated my mother, and how much it sort of ripped her family apart. And it sort of estranged her from her brother for a while. And it was Yeah, it was just sort of, in a way that I remember thinking, like, this is, this is so pointless, like, it's just so stupid. Like, I remember, I remember thinking, like,

What could anybody in my family do that would make me, you know, hate them forever? And it's like, you know, the skin color was just so insignificant to me. And I think that fear shapes everything from geopolitics to just even people's unwillingness to try new things and to go new places and to travel and to ski and to go

Go out and meet people. And it causes so much conflict and it causes so much aggression and hate that I think that, you know, I believe sort of racism is wrapped up in that. But fear, I think, is our bigger problem. Mm-hmm.

My sentence is... The only things you're innately afraid of are falling and loud noises. The rest of your fears are learned and mostly negligible. Meryl Garbus. I lead a band called Tune Yards. Fear is very... What's that word? Compelling as a motivation. Yeah.

It's very essential to who we are, and it makes a lot of sense because we did have to run from things. We needed to be vigilant, and if we weren't, then we died. But I do think that it's a choice. So I thought wanting to communicate as much as possible with this one sentence that it would be good to sing this sentence. Evolving over millennia We learn to fly We learn to fly

were nourished by the fruits of each other's earth inspired by each other's music but we failed as species injured the very hands that fell when we chose fear as our ruler when we could not grasp being mere fractals in one collective being in the end there was no

I was 25 when I realized that I was useless. I just wanted to do my own thing and become a doctor.

It reminds me of this thing called "do-nothing farming" that a Japanese farmer named Masanobu Fukuoka came up with. And he kind of went against all of the established customs of rice farming in Japan and decided to just kind of like pay attention to how things work without any intervention. So he said that he was inspired by an empty lot full of grasses and weeds and how productive that actually was.

And so he went about farming without flooding the fields. He just threw the seeds on the ground kind of when they would naturally fall on the ground in the fall. He didn't use fertilizer. He just grew a kind of ground cover. And then he threw the stalks back on top when he was done. And he just kind of had to do everything at exactly the right time that it would happen naturally. But this farm was more productive and more sustainable than neighboring farms.

All of human effort is meaningless, as he puts it. So he says, humanity knows nothing at all. There's no intrinsic value in anything. And every action is a futile, meaningless effort. Writer Jenny O'Dell. Now, here we go. Writer Maria Popova. We are each allotted a sliver of space-time wedged between not yet and no more.

which we fill with the lifetime of joys and sorrows, immensities of thought and feeling, all deducible to electrical impulses coursing through us at 80 feet per second, yet responsible for every love poem that has ever been written, every symphony ever composed, every scientific breakthrough measuring out nerve conduction and mapping out space-time.

I mean, it's astonishing that we're not, you know, spending every day in Marvel at the improbability that we even exist. You know, somehow we went from bacteria to Bach. We learned to make fire and music and mathematics and

Here we are now, these walking wildernesses of mossy feelings and bramble thoughts beneath this overstory of 100 trillion synapses that are just coruscating with these restless questions. Why? Professor Alison Gopnik. My sentence would be, single word. Let's just leave it alone.

I'd want to show that we loved it here, you know? Animator Rebecca Sugar. We have, you know, evidence from Pompeii. Pompeii's place in history is quite unique in that in one day, it was completely hermetically sealed. In other words, time stood still. We have all of these...

Physical examples. Corinthians the baker gave a party for his brother Neo, who was just elected magistrate. That humans have loved being here. Their friends came and drank all night. That we're having a great time.

So maybe the greatest message a person could leave is to just... This is the atrium of a typical Roman house. Leave behind some record of how you were living. The family life revolved around this area. You know, leave behind your nest and evidence of how you were in it with the people that you loved. You will find that you have small rooms, the cubicles, the triclinium or dining room, which we find back there.

Maybe that would be the thing to leave is, you know, some evidence of my nest. And maybe the ultimate goal would be to just devote oneself fully to creating the life that feels the best on this world in the time that we have. August 24th.

But actually, I think the greatest thing to come out of the ruins of Pompeii is that they had toilet stalls where two people could sit together next to one another. You can have a conversation. It's a fabulous idea. Why did we not learn from this? Why are we wasting time that we could be spending with our friends? Why are we wasting that time? All right. Bath and break. We'll be back in a sec.

Feynman says again. We pick back up with writer Nicholson Baker. Oh, God. Okay, yeah, here we are, here we are, okay. And producer Simon Adler. All things are made of atoms, dash, little particles that move around in perpetual motion, attracting each other when they are a little distance apart, but repelling upon being squeezed into one another. I like it. I mean, I think it's got a certain lilt, but...

Think of you, there was, the cataclysm happened and the creature that inherited the earth was a super intelligent form of seal. You know, there's beaches and they're just covered with these seals and they're still making those strange seal noises, but they're actually intensely verbal creatures. And somehow, some particular seal

gets this thing that comes zapping down from the sky, which is a voice from the deep past or the recorded essence of brilliant scientific knowledge, which is all things are made of little things and they push against each other and sometimes they push back when they squeeze. Well...

What is that very bright seal going to do? I mean, what is that? How? It's going to help them more quickly invent an atomic bomb. But is that where we want the seals to go? Really fast? No, we want them to... Look, they're busy figuring out how to...

better get around the beach, get along with each other, maybe build some kind of nice slide so they can zoom down and fly off and have some fun. There's a lot these bright seals can do. They have a big future ahead of them. So what I would substitute is something that would maybe help them that was very helpful to me, which is that you know more than you can say. It's a

It's a crisp way of saying that language is great. And, you know, I'm in the language business, and I try to create sentences that are momentarily diverting and all that. But language is a tiny, tiny part of the knowledge that we actually have. And not just because there's musical knowledge and the knowledge of colors and

and fragrances and other things that are inarticulable, but because the knack of knowing how to put words together, the knack of knowing how to say in a condensed form a truth is something that involves a feel, a nimbleness, a sort of a set of dance moves that nobody, no matter how good you are at slinging sentences, nobody can articulate clearly

step by step backwards into this world, the understructure of what allowed him or her to say this thing that involved words. So look at what is around you and see who knows how to do things and then learn from that. And the way the person describes how he does things may actually be completely inadequate. You're going to have to watch. We know more than we can say.

That, I think, is the most useful piece of scientific helpfulness, I guess, that you could give. The moon revolves around the Earth, which is not the center of the universe, far from it, but just one of many objects, large and small, that revolve around the sun, which in turn is one of countless stars, mostly so far away that they're invisible, even on the clearest night.

all traveling through space on paths obeying simple laws of nature that can be expressed in terms of mathematics. Oh, and by the way, there is no God. Writer James Glick. And up next is the artist Lady Pink. Okay, so I would like to say God is a female character.

And I would also love to leave behind a mural, something like one of Michelangelo's awesome depictions of God coming in and, you know, grandiose and glorious and absolutely gigantic mural, but as a female. And I think I would like to do her as one of the gray aliens. Do you know what I mean? One of the big eyed aliens with those big, big heads and those big bug eyes like that with real sexy lips and then a little bit of eyelashes.

with kind of looking like the Virgin Mary or like the Virgen de Guadalupe, wearing the long gown and the blue veil thing and, you know, holding her hand up and a little bleeding heart with worshipers at her feet. And because she would be so gigantic, three, four stories, that's like at least 40 feet, 30 feet, you know, very large figure. She would be looking down at you.

I would say that a lot of my childhood, I was thinking a lot about surviving the apocalypse.

You know, how could I do that? How could I be good enough? Writer Jenny Hollowell. I liked the texture of life. I liked the idea of being in the back of the station wagon and driving down the street and seeing my neighbors mowing their lawns or riding their bicycles. And the idea that they would all disappear or not be survivors of whatever that apocalyptic event might be was just jolting.

Meet again, don't know where, don't know when. I was also selfishly along the way hoping that maybe I could get past certain thresholds so that I could experience them before they were gone. Like being able to drive, because I really wasn't sure whether cars were going to be around later. So I remember really hoping that I could make it to middle school so that I could have a locker, because I thought lockers were really cool.

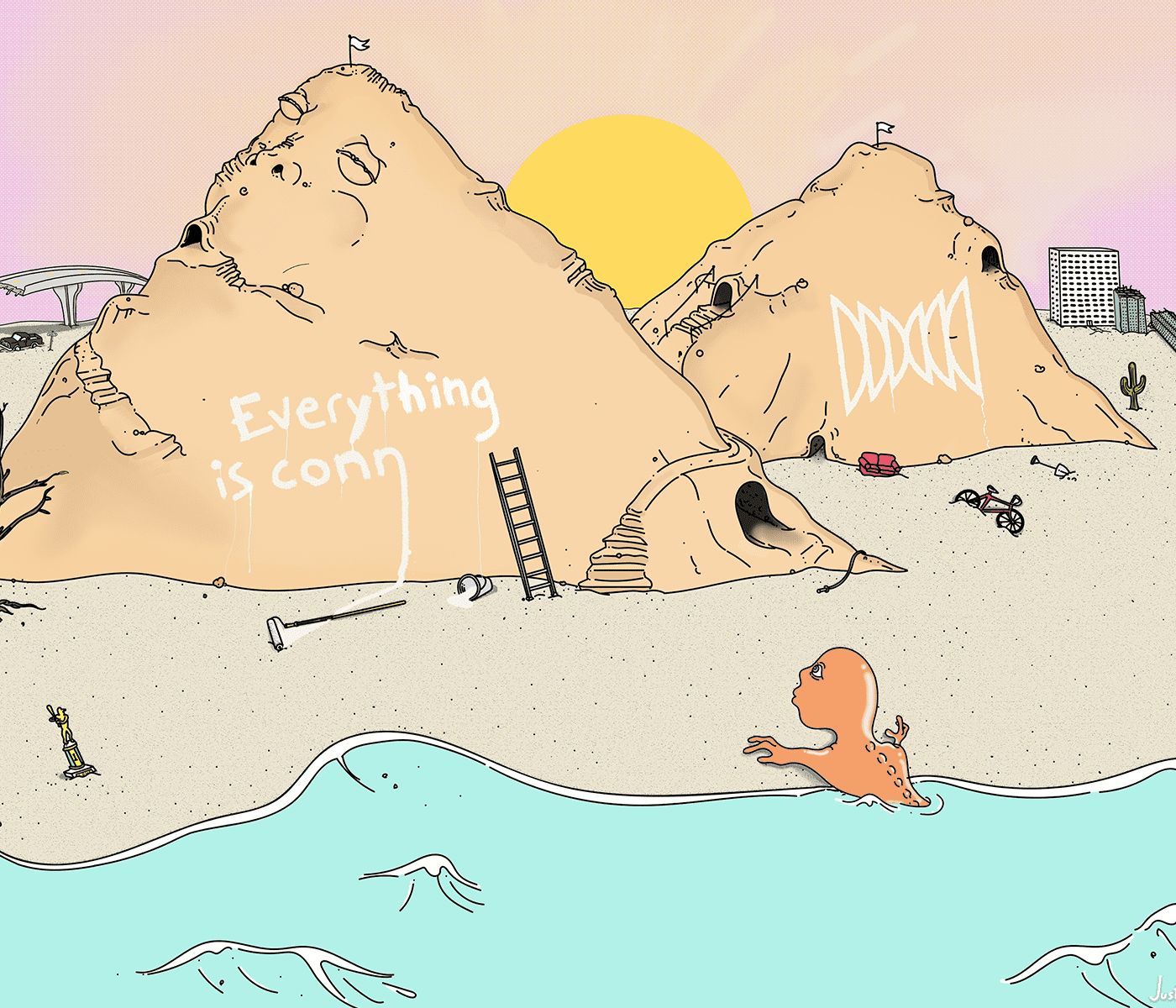

I just thought, like, okay, if I can have a locker and then later drive, then those two things, like, if we can just get past those things, then I'll be a little bit more relieved to see the end come. Maybe. Everything is connected. To me, that feels like a sentence that contains an element of scientific truth, but also something

inspires us to believe in it. Because I do think that whatever we leave behind needs to contain something about it that would inspire the finder of it to believe in it. Okay, up next...

Hello. Hello. Can you hear me? Yeah. Hey. Can you hear me? Yes, I can. Bring back Rachel Cusick. So you and producer Jeremy Bloom talked to someone. Hi, Rachel. We talked to this guy, Jaron Lanier. Do you want to know anything about me or is the name enough? I would love to know about you. Give us a fun fact.

So, Jaren... I'm a computer scientist. He is basically like the godfather of virtual reality and was pretty instrumental in getting the internet off the ground. I also write books and I also play music and...

most notably on a large variety of very unusual musical instruments. Do you have any instruments near you right now? Oh, a couple thousand. So this whole project is like reach out to people you find inspiring and asking them if they have any inspiring things to say. And the reason we reached out to Jaron is because he helped create these huge advances in technology and

the other reason we talked to him is because he actually knew Richard Feynman. Really? How did he know? Well, so... How honest do you want this to be? I want it to be as honest as you want it to be. Well,

Well, he said this is back in the late 70s. I was 16 or 17 living in New Mexico. And what happened is my first serious girlfriend was someone I met over a summer. She was visiting from California. And I followed her back to California where it turns out her dad was the head of the physics department at Caltech. And after a while, she dumped me. And there I was. Oh, no.

What was I to do? I'm still there. And so I just hung out more and more with people in the physics department. Do you remember where you were when you first saw Richard Feynman? Sure. I was being walked down a hallway by my friend Cynthia, and he was in there walking.

explaining something to a small class of people with his hands, primarily. He talked with his hands a lot. And she said, there's the famous Feynman. And of course,

My very first thought is, oh, damn, he's like the smartest person alive. And he's also handsome and he's happy and he's graceful. Like, fuck him. Oh, I can't say that on the radio. I'm sorry. You can say it. I was like, oh, my God, this guy's just like, it's not fair. This guy just has too much going for him.

But Jaron says as he got to know him... He was just fun and funny. The two of them would talk about physics and just about life. He played percussion. He played drums. They'd play music together. Which was great. His primary approach to life was to seek joy.

Do you remember him asking you about cataclysms ever? I definitely remember that topic in that conversation because... Remember in those days we were in the thick of the Cold War. Hey!

Duck and cover. And in school, you were trained to hide under your desk in case there would be a nuclear attack, which of course everyone knew would be a futile gesture. So this question, it was like a little glimmer of hope, like in the face of absolute annihilation, where hiding under your desk will not help, where hiding in some basement will not help, where you won't survive. This is at least...

It's applying imagination towards what you possibly could do. Maybe you could leave a message for the future. We talked for a while about how much Darren really loved this question because like he and Feynman and these other physicists, they'd hang out and kind of talk about this question for hours.

And they would debate about what was the best thing to write down on this piece of paper, partially because it was fun, but also because it felt important to have an answer. But then when we asked him what he now would write down as his cataclysm sentence... You personally, Jaren, what would you do? He took a deep breath and then said... I would give them nothing. Huh. Like nothing, nothing? Zilch. Does he mean like the paper fluttering in the breeze that lands in the hand of the next person?

it would have nothing written on it? He means like there's just no piece of paper at all. Yeah.

That seems kind of sad to me. Like, why wouldn't you want to leave them something? Well, let's see. Jaron's like, let's just say you do leave behind a sentence about the basics of math and physics or agriculture and medicine or some sentence about biology or public health, that sort of thing. It's redundant. Like all of that kind of information is just the stuff that's out there waiting to be discovered in nature anyway. So we don't have to do anything.

If people apply themselves, they'll rediscover all that stuff. So it's not like we're special. Letting them get it in their own good time might be better for them. So what have we actually added? Perhaps we've only taken away. Taken away because giving some highly evolved science facts kind of scared him. Because Jaron thinks, like, you never really know how those are going to unfurl in another world. Right.

I mean, look at Feynman's sentence. It gave us all of these cool things that we talked about up at the beginning, but it also gave us... The atomic bomb. Don't wait. Duck away from the windows fast. The glass may break and fly through the air and cut you.

I mean, Feynman and others in his generation who'd come of age working in the Manhattan Project were put in an absolutely impossible moral puzzle where bringing the war to an end decisively was a great good, and the other side in the war had been the darkest evil.

All of that was clear, and yet in the big picture, it was just impossible to know if they'd done the right thing. And that cloud of doubt still hangs over science today. For example, Jaron says... Like, I was very involved in the birth of the internet. Look at the internet. That started as this amazing gift to people so that we could connect in this way that we never had before, but...

As we now know, it spreads disinformation. There's every economic incentive to be terrible. And the incentives to be decent are far, far weaker. And I still have this incredible feelings of guilt and uncertainty about whether we just screwed things up terribly in a way that might take centuries or millennia to fix or something like that.

There's just this haunting, this feeling of like, oh my God, what have we done? Was it the right thing? So we suggested like, what if it wasn't a piece of science, but like a piece of wisdom, something you would kind of like find inside of a fortune cookie? Well, that becomes a very interesting exercise. And what you realize is whatever little words of wisdom you can pass along, because the whole terms of the game is that they'll be isolated, they'll take on this

of outsized preciousness. They won't be surrounded by context. And almost anything you can say will become distorted and somewhat useless if it's overemphasized in that way, which is to say, nothing we can do is helpful. Let's just lay back. Let's be modest. What if you were on the other side of that? Like, what if you were on the other side of the cataclysm and you discover that you're not going to get anything at all?

Well, I mean, if there's nothing given, how would I even know that there was nothing given? I don't think I'd even be aware that there was something to have feelings about. That's fair. I don't know. I feel like sometimes when you walk into an empty field or something, you're looking for something if you're kind of feeling lost. Okay. So there's people in the future and they find our ruins. And then there's some big plaque that says, we have decided to leave you no information. You will learn nothing of us.

If these next people might turn out to be wiser than us, or if they don't and they extinguish themselves, then the next generation after that, at some point, if some kind of cycle of cataclysm and civilization continues, at some point, there'll be some civilization that's wiser than us and won't annihilate itself anymore.

And let's just not screw with these people. Let's just give them a chance to come about naturally, and they will eventually. But that's an optimistic viewpoint, too. Like, if we seem to keep, like, exploding ourselves, how do you have faith that we'll get there ever? Just because of the reality of randomness. What does that mean?

I love that phrase, but I have no idea what it means. It's a little bit, it's like a version of evolution. Like, let's just assume that there's not just going to be one cataclysm in another cycle, but we'll keep on going through these things until just through the grace of randomness, we get some civilization that comes up that's got its act together enough to not have another cataclysm. And I think there's something to be said for that. It's like some kind of faith in the far future that will finally get it together. Yeah.

So that was basically his answer. Like, say nothing, have faith, trust the math. But if you today had to go back to you as a kid, we kept pushing him. Would you have a specific sentence that you would share with a younger you? Oh, gosh. And each time... Is there a sentence that you would say to start us in a more optimistic light? He pretty much didn't budge. No, I don't... Except when Jeremy asked him...

There's one question. If you could leave music for the next society, would you? That is a really interesting question. So, you know, one of the things about music is that it's an incredibly important part of our lives. It's part of every time we have a wedding or a funeral. It's incredibly important to us. And yet, until very recently, with the appearance of recording technologies—

It was lost generation to generation. I play all these weird instruments. He demonstrated for us. There's a kind of flute played by the Sami people of Finland. And part of it is this feeling of being able to at least move and breathe like people did in the past. This is an instrument from Laos. So you get a little bit of connection with them, but of course you don't really know. ♪

This is a contrabass flute. If you could leave an instrument for the next society that maybe could say something about our society, would you? That was called a tarhu. I don't know. That's a very hard question. This is a kind of Turkish clarinet. I'd have to think about that one a lot. I think I'd... The oud. The oud.

A Middle Eastern instrument. Possibly choose the piano, I hate to say. Why the piano? The reason the piano fascinates me is it's kind of a digital button box like a computer, but it transcends being a button box. Because on a piano, you hit the key and then you send this hammer flying. And the only thing you can tell the hammer is how fast to fly. So you would think it shouldn't be very expressive. And yet...

Different pianists sit down and have touches on it that are distinguished. I believe there's a bit of a mystery left there. Okay, to round things out, just so happened...

that somebody that I really wanted to talk to for this episode is a composer who plays the piano. Her name is Missy Mazzulli. She is very busy at the moment. She has two operas opening pretty much at the same time. Her work's been performed by orchestras all over the world.

And we asked her to come down to our station at WNYC where we have a piano. Do you want water or anything? Yeah, he was going to get me water. Oh, okay, great. Also a Rachel. Okay. Because, you know, going back to the whole conceit of this thing, one of the questions that I had at the very start of this was, if we gave this Feynman cataclysm sentence challenge to a musician, what would happen? We could start talking just in a moment.

Yeah, we can start. So you came up with a musical answer to this question. Yeah. I call it the primordial chord is my name for it. Oh, that's cool. So going along with this idea of setting humans 2.0 or the next version of creatures up for a better existence, I wanted to create

something that would point them in that direction so I wanted there's a couple things about this chord that I hope will do that so this is a chord that has to be played by three people you cannot play this chord by yourself unless you have six arms which maybe these creatures will have but you know you need three people to play it and why'd you pick three people um

That's a good question. I think that's what I felt could fit at a piano. And so, and I, and I chose a piano because it's generally the biggest instrument that we have general access to in New York City right now. And I wanted it to, it has the biggest range of musical instruments that we use every day. There's certain, there is music that is maybe higher and lower, but in general, like most music you hear in the world fits into the range of a piano. Yeah.

So this chord encompasses the whole range of the piano. We use the lowest note, we use the highest note, and it also has all 12 notes of the Western chromatic scale in it. Oh, interesting. And they're also... That's going to sound like chaos. It's not, though. It's ordered. I've ordered it so that it hopefully does not sound like chaos. Yeah.

Anything can happen. I don't know. I so want to hear it now. I know. So do I. Can we do it? Can we play it? Let's go do it. So we had to get up and go over to the studio where the piano is. Okay. So we are here in CR5, or as we like to think of it, John Schaefer's studio. There's the big grand piano to our left. We're going to follow your lead here, Missy. Okay. So Missy pulled out the sheet music. This is a primordial chord.

Oh, my God. Okay. So if you imagine a page of orchestral score, we've all probably seen one at some point. You've got the lines running horizontally across the page. The page was mostly blank except for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 notes. Yes. You get 13 little circles all stacked up in a vertical line looking kind of like a rocket about to take off. And you have three clefs. So each one is one human. Okay.

Yes. So each grand staff is one human being playing one piano. Okay. How long did it take you to come up with this? It took me a shockingly long time. Because I kept fiddling around with it, playing with the resonance. You know, sometimes I would come up with something and I felt that it was too dissonant. It's also a challenge to come up with a chord that includes all 12 of these notes, you know? So like...

So all 12 of those spread out over this huge range that still has a sort of consonant feeling to it. It's interesting, when you look at the chord, this giant chord which contains all the notes in a scale, she's arranged it so that you can see in the chord all of these kind of musical molecules. Like, oh, those three notes in hand number four...

That's a major triad. And these two notes in the bass, that's a tritone interval. And then, okay, look at that. In the upper register, that is a diminished chord. And if these words don't mean anything to you, it's fine. The point is, is if you zoom into this chord, you see all of these harmonic universes ready to spill out.

That's why she calls it the primordial chord. Should we do it? Let's do it. Okay. We can sit down maybe. Okay. Okay. Is that okay? Yeah, you sit and then maybe Rachel and I will get like half a cheek. Yeah. Okay. Together we'll be a cool bunch. So Missy sat in the center of the piano bench. I was sort of hanging off the left side, half a cheek. Rachel was hanging off the right side, half a cheek. Okay. Cool. Perfect. So far, so good. Okay. So...

Jack, I'm going to set you up. So I'm going to just play it for you. These are your four notes. Love it. Okay. Okay. Perfect. Perfect. And then these are your, you have five notes. Okay. One, two, three, four. Is he's rolling over there? No. Okay. That sounds pretty good here. And it's very easy to show me one more time. No, it's okay. I'll show you a million times. Okay. Yeah.

Okay. So we'll just build it low to high. Okay. Should we build it sequentially or do we want to try like a boom? Oh, let's try all together first. Okay. Let's try all together first and then we'll build low to high. So let's see if we can. Okay. So there's like an upbeat and then there's one, two, three, four. Hit. Okay. Okay. All right. We're up. Keeps going. Yeah. It never stops. Maybe forever.

What if we have to go to the bathroom? This is it. Welcome to the rest of your life. You're just stuck here holding this cord on the piano. I'm afraid to let go now. This is a big response to the weight of the world. Ready and... That was awesome guys!

You're so good! Oh my god. I'm so proud of you. It feels like the end of a movie. It really does. I feel like I got the best part. I got the bass. It's just like everything I do sounds good down here. See, I like mine up here. It's really nice. See, I feel totally safe between the two of you. We're just like hanging out in the middle. I feel like I'm the foundation of this new society. Yeah, but I give us hope. I'm the glue. See, we all need each other. That's the point. It is. It's like a full human being.

Okay, Lulu, Latif and...

Rage from the future now. Okay, so did you ever like do the prompts? Like what would you write on the scrap of paper to toss into the post-apocalyptic wind? There's so many times in this job where I'm like, thank God I'm not you. Like I call up these people and I like ask these things of them and I would never feel like I had all this information and like knowledge that they have. And especially this one, like I worked on it for an entire year and I would constantly ask like what my sentence would be.

And I would not have an answer for you. Well, good thing it's three years later and you've thought about it and now you have an answer. So when we can put that question to you right now for this exact moment. I actually, so I was thinking about this sentence that I had heard that Ram Dass said, which is like, we're all just walking each other home. That's beautiful. Like we're all headed towards the same grim place and we're all headed towards different places in our lives. But

all we have is like each other in those moments and keeping each other company and like making us discover new things and yeah, like making us bump into ourselves. And, you know, there's just thinking about like walking on like a quiet little road home from school or something. And like every single person in your life has gotten you a little bit closer to that door. That's really beautiful. I have to pick my head up out of my hand. Yeah.

Because I'm so like throttled by that. That's so beautiful. And I think it's the most beautiful thing when I think about this team and like everything that it means and also just like who we are to each other. Like it is engraved in my soul as if there's a tattoo of this exact feeling in me. But that moment in the episode early on when like

I'm just talking about this feeling that I had as a kid and this, like, sense of loss. And then from there, you go to, like, the sound of the phones being dialed up and this, like, cluster of, like, hello, hi. Like, is this who? And that feeling of, like, everybody just pitching in. It almost felt like all of those people transported back to, like, childhood me and were, like, giving me this, like, beautiful gift. And it's so special. Whew.

I just think like this show is this like huge gift in my life. I think it's like so special to have a place just like bring you closer to yourself. Did you hear anything in particular listening on this second time around differently? Was there anything that stood out to you? Yeah. It's funny that you ask that because I listened back to it for the first time in years and

And I think about it when I like before I had listened, I was like, okay, this is a pandemic story. This is a grief story. This is about destruction. And then I listened to it with the kind of mindset of leaving and moving and being like, oh, okay.

I'm the person on the other end of the cataclysm, like, walking in. Like, I think I had been, before making the story, I was feeling the need to gather all those sentences. And now I feel like the person who's receiving all of them. Like, the person picking it up on the other end of the cataclysm. And it's like, I was able to listen to it last week with just like, oh, this is like what I get to like start a new life with. These sentences. And the ones that stood out to me now are...

Like, I love all of them still, but the ones that stood out to me now are way different than the ones that I listened to with grief and loss in mind rather than, like, starting anew. Whoa. Yeah. And now I'm like, wow, I have this, like, wealth of beauty and wisdom in this little episode for me to, like, start with. I'm, like, starting at the Monopoly, like, square one. I just got $200. Like, here we go. Yeah.

Alright, I guess we just say... You say goodbye, Rachel. Yeah, you say goodbye. Goodbye. Yeah, I'm an Irish goodbyer. Can you just cut this episode right here and just drop it off the face of the earth?

P.S. This won't be the last time you hear Rach. She's got a great story coming down the pike. And if we're lucky, even more after that. Production this episode by the entire Radiolab team with update help from Sara Khari.

Special thanks. There are a few of them, so bear with me. Our friends over at the former podcast, Nancy, producers Zakiya Gibbons and Jeremy Bloom. Also, Ella Frances Sanders and her book Eating the Sun for kicking this whole thing off. Caltech for letting us use original audio of the Feynman lectures on physics. The entirety of the lectures are available to read for free online at

finemanlectures.caltech.edu. That's F-E-Y-N-M-A-N lectures.caltech.edu. We also want to thank all of the musicians from all over the world who, after the pandemic set in, recorded themselves in their homes and sent us the audio.

And also good old Alex Overington used that to make the giant primordial chord that you just heard. Their names are...

Sansevier, Quebec. Matthias Markus Kovacek, Germany. Hi, I'm Curtis McDonald, and I'm from Canada. Hilario Morciano, Northeast Italy. Brian Harris, Richmond, Virginia. Saskia Lankhorn, The Hague, the Netherlands. This is Mead Bernard from Brooklyn, New York. Also thanks to the three musicians who didn't ID themselves, Sam Crittenden in Brooklyn, Barnaby Raya in the UK, and Siavash Kamkar in Iran.

All right. And before we let you all go for good, I just wanted to give a shout out to a podcast called You're Wrong About. It's a wonderful podcast that does deep dives into histories. If you aren't already in love with it, go find it. I was lucky enough to join on their most recent episode to do a deeper dive on some of the stuff we talked about in the seagulls episode and actually share a bunch of stuff we left out about the history of scientific suppression of queerness in nature. And it ends with a really special little emotional dollop.

So go check that out, You're Wrong About. Enjoy it wherever you get your podcasts. Thanks so much. Bye.

Our staff includes Simon Adler, Jeremy Bloom, Becca Bressler, Rachel Cusick, Akedi Foster-Keys, W. Harry Fortuna, David Gable, Maria Paz Gutierrez, Sindhanyana Sambandang, Matt Kielty, Annie McEwen, Alex Neeson, Sara Khari, Anna Rasku-Ekbaz, Sarah Sandbach, Arian Wack, Pat Walters, and Molly Webster. With help from Sachi Kirijima-Molke. Our fact checkers are Diane Kelly, Emily Krieger, and Natalie Middleton.

Hi, this is Finn calling from Storrs, Connecticut. Leadership support for Radiolab's science programming is provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Science Sandbox, a Simons Foundation initiative, and the John Templeton Foundation. Foundational support for Radiolab was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Ever dream of a three-row SUV where everything for every passenger feels just right? Introducing the all-new Infiniti QX80, with available features like biometric cooling, electronic air suspension, and segment-first individual audio that isolates sound.

Right to the driver's seat. Discover every just right feature in the all new QX80 at infinityusa.com. 2025 QX80 is not yet available for purchase. Expected availability summer 2024. Individual audio cannot buffer all interior sounds. See owner's manual for details.

Squeezing everything you want to do into one vacation can make even the most experienced travelers question their abilities. But when you travel with Amex Platinum and get room upgrades when available at fine hotels and resorts booked through Amex Travel, plus Resi Priority Notify for those hard-to-get tables, and Amex Card members can even access on-site experiences at select events, you realize that you've already done everything you planned to do. That's the powerful backing of American Express.

Terms apply. Learn how to get more out of your experiences at AmericanExpress.com slash with Amex.