Chapters

Shownotes Transcript

Support for Violation comes from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, committed to building a more just, verdant, and peaceful world. More information at macfound.org. WBUR Podcasts, Boston. The fullness of time. The fullness of time. That phrase has haunted me since I first heard it or read it.

though I don't know when or how the words entered my awareness, because they seem always to have been there, like certain melodies, for instance, or visual harmonies. That's John Edgar Wideman, Jacob Wideman's father. He's 82 now.

Jake had been in prison seven years when John wrote this essay called Father Stories. And in it, John reflected on how those years had passed in an instant and somehow also in eternity. Time can drag like a long string, he wrote, studded and barbed through a fresh wound.

Jacob Wideman killed Eric Kane when they were both 16, when Jake was wrestling with heartache and suffering that he had shared with no one. Eric was just barely entering adulthood. He left behind a brother and a sister, parents who adored him. I can't know how time has passed for Eric's family, but I wonder if they've experienced a similar phenomenon.

Whether the day they lost Eric will always feel like a minute ago and impossibly long ago. Fresh and painful and an ancient hurt at the same time. The fullness of time, neither forward nor backward. A space capacious enough to contain your coming into and going out of the world. Your consciousness of those events, the wrap of oblivion bedding them.

A life, the passage of a life, the truest understanding, measure, experience of time's fullness. Jake is 53 now, older than John was when he wrote Father Stories. At that time, Jake had a number he was counting down towards, 25 years. His sentence was 25 years to life.

Although he always knew it was possible he would live his whole life and die in prison, he also knew that after 25 years he could start making his case to the parole board. And that gave the time a shape, a destination. Now, more than six years after he was brought back to prison, he has lost that destination, that checkered flag flapping just past the horizon. And time just passes.

When we talk about going to prison, the phrases we use inevitably involve the word time. Doing time, serving time, as if time were a commodity like money that can be spent, earned, lost, owed, or stolen. As Jake's dad, John Weidman, reflected in Brothers and Keepers, the book he wrote about his brother Robbie's life sentence,

But as John writes, incarceration as punishment always achieves less and more than its intent. Because, of course, you can't take people's time away. You can only make it more painful, more solitary, more slow. As John wrote, no one does time outside of time.

Jake and the people who love him are deeply aware of that, especially as court filings and deadlines have come and gone. It's been a rough time. It really has been. But, I mean, what is there to do except keep moving and keep pushing forward and, you know, keep hoping that things will be done correctly in the end.

It was December 2022 when Jake's attorneys submitted their last special action, that appeal where they argued that the parole board had treated him unfairly when it revoked his parole. Then waiting. August of 2023 when the judge heard arguments in that case. Then waiting.

The judge was supposed to issue a ruling within 60 days, but it was more like 74 days in mid-October by the time he actually did. More waiting. If it had been him sitting in a cell somewhere or his son or his daughter or anybody he cared about, I would imagine each of those 24 hours would have meant something to each one of the hours of the 24 would have meant something. Jake's mother, Judy, passed away in June at 80.

shattering Jake's hope of ever seeing her again outside of prison. John is angry about a lot of things about Jake's parole revocation, about how the system, as he sees it, bent to the will of the Canes. But the judge's delay was particularly frustrating. Took his own good time, and the good time is my son's time, the only time my son's going to have on Earth. I'm Beth Schwartzapfel.

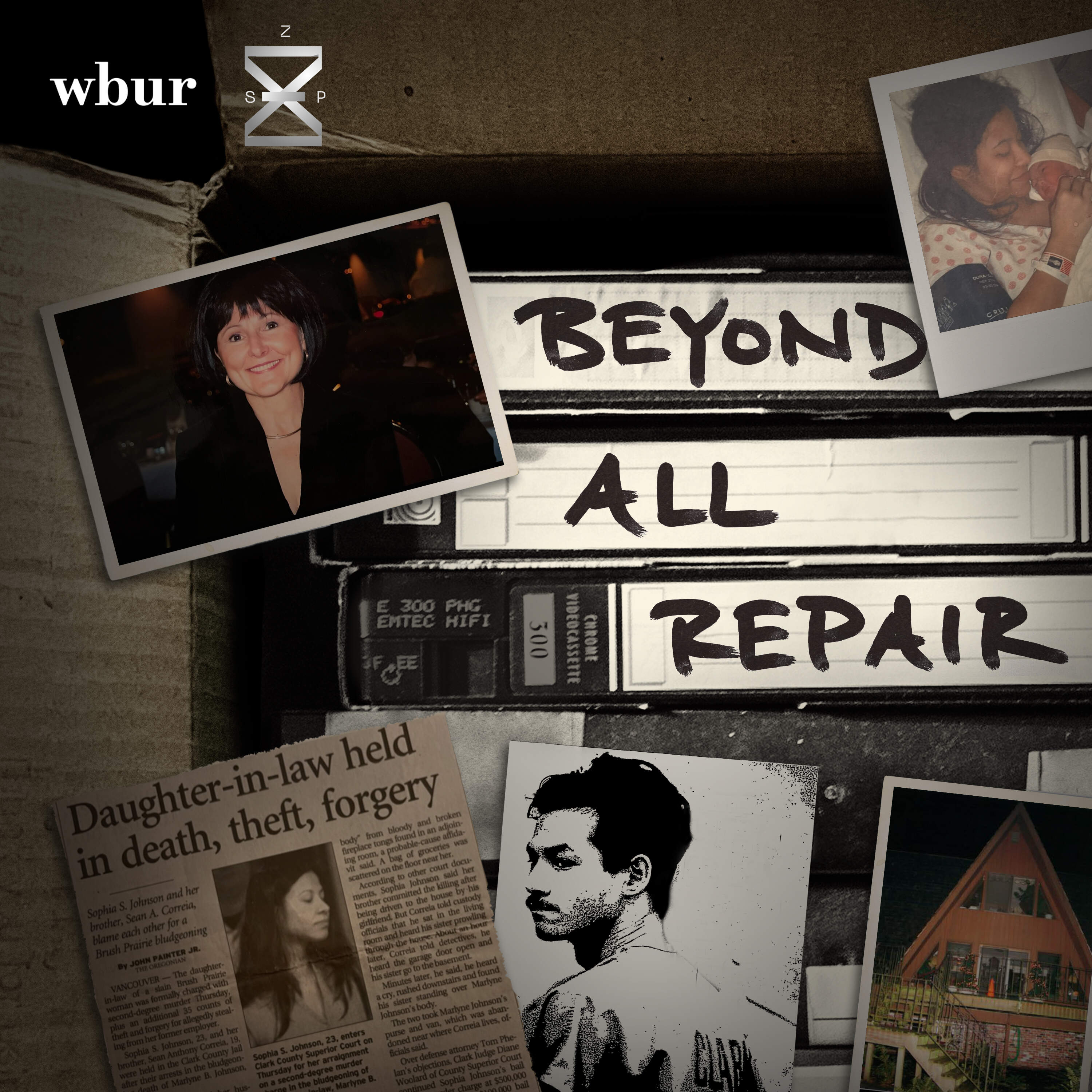

From the Marshall Project and WBUR, this is Violation, a story about second chances, parole boards, and who pulls the levers of power in the justice system. This is our eighth and final episode, The Fullness of Time. When we were making Violation last year, in the spring of 2023, we had no idea what this final episode might look like.

Would we be covering a new parole board hearing if the judge ordered that? Would we be standing outside the gates of an Arizona prison watching Jake walk back out again if the judge, in an unlikely but not impossible scenario, ordered that?

Or would we find ourselves here, right back where we started, with Jake sitting in prison, filing legal briefs and arguments and appeals, trying to get some judge somewhere to agree with his point of view that he should never have gotten locked back up in the first place? It's just unfair what happened. And to the extent that I believe in this system, that it works, it needs to correct that unfairness. And I'm confident that it will.

Jake's attorney, Josh Hamilton, said he plans to file an appeal shortly to the ruling issued in October by Judge Mark Brain. It could take a year or more for that process to run its course and for that court to issue a ruling.

The new governor is appointing new parole board members, as the ones appointed by prior governors retire or move on. And maybe at some point, the composition of the parole board will change enough that Jake will be willing to go before the board again, like he did all those years, and begin asking again for his freedom. But that would require him to abandon his legal appeals, something he's not ready to do yet.

So for now, he will appeal again and again until they exhaust all the state courts. And then, if need be, they will begin appealing in federal court. That could be years and years and years, says Jake's lawyer, Josh Hamilton. I will not stop until either I'm dead, Jake's dead, or he's out.

To Josh, it looks like the state cut corners, committed, quote, egregious constitutional and statutory violations in putting Jake back in prison, he argued to the court. That's not how the system is supposed to work, Josh says. The board, of course, said it did no such thing.

The board's executive director declined to speak with me about it because the case is ongoing. But in court filings, they said they followed all the rules and that Jake's, quote, disappointment with the outcome of the second revocation hearing is not a basis for a due process claim. I've lost sleep over this. It upsets my sense of, it calls into question everything I understand and believe in about the system.

Now, you might be rolling your eyes right now. Jake stabbed a defenseless kid who was sound asleep for no apparent reason. A 16-year-old who had barely begun to live his life, who went away to summer camp and never came home. We certainly heard from people who thought Jake had no business complaining about justice or fairness. Hi, my name is Jenny.

This is a listener who called our phone line. I don't have a question, but it said to also leave an opinion on all of this. And I believe the case was handled fairly and that Jake got what he deserved. The question of what Jake deserves is still unanswered. Is unanswerable, really, because it depends on who you ask.

The Supreme Court has said that people who commit crimes when they are young should, in all but the most extreme cases, have another chance. And Jake was a kid when he killed Eric, a kid suffering from the effects of early childhood trauma and undiagnosed mental illness. But how do you weigh all of those truths? In the fullness of time, does the right thing to do become any clearer?

Hello Beth, this is John in Tucson. The question you ask, "Is there anything Jake can do to deserve being released?" isn't quite the right one. Jake has done more than enough to show that he deserves to be released, that justice would be served if he were to be released. This is John Weidman's old friend, retired English professor John Warnock, who has known Jake since he was a boy.

He called our listener line, too. The problem here is that the victim's family is so relentless in its wish for retribution. You can't fault them for that. But the state has an obligation to decide when it's enough. We're not in a system where the victim's family gets to draw and quarter Jake.

There's no evidence that the Keynes played a role in Judge Brain's decision. But Professor Warnock is naming this sense, among those in Jake's family and his legal team, that the Keynes' very unusual degree of involvement in his case played a role in the very unusual way the department handled it.

The Kanes, you might remember, obtained data from Jake's ankle monitor and submitted a lengthy report about alleged parole violations and urged the department's top attorney to arrest Jake. And when parole officers did arrest Jake, they did it because he left a message for a psychologist but could not reach him in time to make an appointment as requested by his parole officer.

That psychologist, Dr. John McCain, agreed with Jake that their missed connection did not feel like a good reason to bring Jake back to prison. Dr. McCain texted me in April. He wrote, Episode 6 was a reminder of how incensed I was about his parole officer, who had no interest in Jake's well-being as far as therapy and was simply looking for any excuse to violate him.

I continue to regret how I was used in this disingenuous display of concern for Jake's transitional mental health needs. It's one thing to dispute an opinion. We're used to that in forensics. Experts have different opinions. But what I'm not used to is somebody taking my opinion and bending it to represent an opposite opinion and then attributing that opinion to me.

McCain, after all, was not only a psychologist who Jake was supposed to see on a particular date in order to satisfy his parole requirements. He's also, you know, a psychologist, i.e. an expert in human behavior. There was nothing that suggested any reticence or avoidance of him trying to set up an appointment with me. And I'm used to and schooled in being able to identify what that looks like.

But at the end of the day, it's not up to McCain what to make of their misconnection. It's up to the Corrections Department and the Parole Board. It's up to people like David Neal. My name is David Neal. Now I'm 74 years old, but I spent a total of 26 years in law enforcement. Remember David Neal? He served on Arizona's Parole Board in the late 2010s.

He voted on Jake's case twice. Once in 2017, when the board officially revoked his parole and said he'd stay in prison indefinitely. And again in 2020, when a judge ordered a do-over of that hearing, and the board again revoked his parole and said he'd stay in prison indefinitely. It's not surprising that a judge would deny him anything because he was that sort of a person. What does that mean?

David thought Jake was narcissistic, manipulative, self-centered, he told me. With Weidman, it's hard to describe when you're, you know, how when you're talking to somebody, you know, a lot of nowadays they say, oh, well, his vibes are bad. But that's the thing about Weidman. He came in and you can just see the arrogant attitude, better than thou attitude. But he didn't feel that way about everyone.

At times, he voted in favor of people who had committed very serious crimes. But I still think that, you know, people are rehabilitatable. We had a lot of prisoners came up, I mean, and for parole type, you know, they're murderers or rapists or, you know, things like that. And they put a lot of effort into making themselves worthy of going back in the public.

It's remarkable to hear David say this, and bear with me while I tell you why. Because beyond his work as a cop, and then a crime scene investigator, and then a parole board member, David Neal also spent years volunteering for a group of people who lost family members to murder. Because he himself lost a family member to murder.

It was actually a friend from this group that encouraged him to apply for a spot on the parole board so he could bring a victim's perspective to the board. In 1999, Neal's grandson, Jared, was beaten to death by his mother's boyfriend. He was three when he got, you know, he turned three in May and then like, you know, a month and a half later, he got, that's when he was killed.

After Neil's son and his wife split, she and their two kids moved in with a man named Brad Rakestraw. Rakestraw is serving a life sentence for murdering Jared. He will never be eligible for parole. You know, I was pretty much law and order on the police side of things all my life.

And now all of a sudden, I got flipped really quick into big-time victim side. Neal says that of course it was hard for him when people came asking for parole who had killed kids. It was hard for him when people had killed cops, too. But he always gave people the benefit of the doubt, he said. Before we go any further, let's talk about why David Neal is no longer on the parole board.

He was removed from the board in 2020 after he voted on Jake's case, after he voted on hundreds of cases, after a human resources investigator sustained several allegations against him. According to the state investigation, quote, Mr. Neal has on multiple occasions made comments in regard to not believing in mental illness, that psychology is not real science, that all inmates are guilty and should never get out.

Also that, quote, rural Mexicans tolerate child molestation. An administrative law judge upheld his removal from the board in 2021. As part of the investigation, Neal responded that there may be some slightly questionable behavior on my part, but insisted many of the allegations were, quote, false and verging on slanderous and possibly libelous.

If and when Jake ever goes before the board again, the decision about whether he deserves to be free will rest with five people, like David. Five complicated humans with tragedies and motivations and biases that even they might not understand. Whatever five people happen to suit the governor for whatever variety of reasons when there happened to be a vacancy on the board. Did Jake get what he deserved?

David was one of a very small handful of people who was actually in a position to answer that question. And his answer was, yeah. I always prided myself on being able to, I don't want to say judge, but determine character of people, and fairly quickly. And being raised by a cop, and then, you know, 26 years total in law enforcement, and then go on a parole board, it's like, hmm.

But, you know, I was pretty good at it. And some of those people coming from, you know, as soon as they come up there, you know that this person is just not somebody you want back out in society.

And so time passes. I mean, when you're young, you don't understand time. You know, it just comes to you. And then suddenly you're behind the bars and, you know, what's going to happen to me? How long am I going to be here? And so part of the fight of younger people, I think, as I notice in my brother and my son, is denying time.

All I have to do is kick ass and make noise and maybe the time will go faster or maybe this time doesn't even exist or maybe I can end it. But it doesn't end. John's brother Robbie served almost 44 years of a life sentence before he was released at age 68.

He was involved in a 1975 robbery that left one man dead. And though Robby didn't pull the trigger, he was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole. Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf commuted his sentence in 2019. The people they have become, the men they have become, the human beings they have become, is partly making sense of those vast stretches of time in which they are living.

in which most people forget about them. I can't, of course. And if my writing has any effect, one effect that I would hope it would be that it reminds people that the preciousness of time that is all any of us get

Another person who has a lot of power over Jake's future is this guy. Governor Katie Hobbs made her pick last week for the toughest job in her cabinet. The state's new prisons director will be Ryan Thornell. Thornell took over promising a whole host of reforms, including revamping and expanding the prison's rehabilitation and job training programs and the prison health care system.

He has a Ph.D. in public policy, and he says he's committed to following the research about what works. For me, it's really about coming in and doing a few things. One, committing to being transparent and having open communication.

So any person, staff member, public who reaches out to me directly gets a response from me. I mean, an Arizona corrections director willing to answer my questions? Yes, please. What does a good parole officer do? What do they not do? What my hope is, and I think the direction that you would find our community corrections group going through now, is really that case management perspective.

supportive model, the brokering of services model that is anchored in a level of accountability. And when I say accountability, I don't mean the old trail them and jail them sort of approach of accountability. What I really mean is this idea of laying out a plan for an individual based upon whatever it is that they need and then helping them achieve that plan.

I asked Thornell how he instructs his parole staff to handle technical violations. Failing a drug test, not checking in with your parole officer, missing an appointment. Behaviors that may violate the rules of someone's parole, but aren't crimes. We know that by and large a technical violation

isn't always, you know, a solid reason or a necessary reason to reincarcerate somebody. Our approach is we need to intervene the least amount possible for whatever that situation is. As you can imagine, like inevitably, this leads to my next question about Jacob Weidman, right? So he was rearrested and reincarcerated for not setting up an appointment with a psychologist. I know this was your predecessor, but look, but he's still in prison in Arizona under your administration and your administration is still defending that in court.

as recently as August. Do you feel like he belongs in prison as a result of that technical violation? So I was certainly not going to discuss the specifics. As you mentioned, it's still going through the court process. And it happened two administrations before me. He's right that it was two administrations because remember Charles Ryan, the former director who was in charge when Jake was rearrested, the guy who had an armed standoff with police at his house?

By the way, Ryan pleaded no contest last month to misdemeanor gun charges in a plea deal related to that incident. The former head of the Arizona prison system, accused of illegally firing a weapon and pointing a gun at officers, cut a deal with prosecutors today. After Charles Ryan retired in 2019, there was another director for two years, David Shin, before Thornell began.

anyway. What I can tell you is, back to my point earlier, you know, our approach would be that when somebody's behavior necessitates any level of intervention, the necessary intervention is what is least necessary. And so in a situation that doesn't warrant

re-arrest, re-incarceration, we would figure out, you know, my expectation would be we have a responsibility to figure out what we do with them in the community to keep them in the community and address whatever that concern is, whatever that behavior is, rather than re-arrest and re-incarcerate them. So not to, you know, but it sounds like you're saying if you were in charge when that happened, this would not have been your approach? I don't want to put words in your mouth.

Is that a fair assessment of what you just said? I don't know that there's going to be a fair assessment. I wasn't around when the situation was unfolding, right? So I only know certain parts of what happened.

Whatever the case may be, the facts might have been at the time. All I can tell you is what my approach is today, how that situation fits into my approach. You know, not always apples to apples, but I will just reemphasize that my approach is we only rearrest, we only reincarcerate when it's necessary, when there's a public safety issue at play, when it's warranted, and the other interventions, the other efforts that we have at our disposal have failed.

It's a Saturday morning in Arizona, and Jake's wife Marta is on her way to visit him at the state prison in Tucson.

It's been four months since her last visit. Now I get to, like, drink really nasty coffee. And just terrible hamburgers and Fritos and all that nasty stuff. Oh, it's horrible. I know. Though Marta and Jake have been married for 11 years now, they've only ever spent a few months together outside of prison.

She's going to spend the day with him, eating bad food out of the prison vending machines and walking in circles around the yard, talking. There were only a few months when Jake had his own apartment, and a lot of those nights Marta was at her own house with her kids. But the days they did spend together, they were beautiful, Marta said. In the car ride to the prison, she told her friend about how she and Jake would wake up early Sunday mornings to go hiking.

We would just start tying our shoes, not even talk, you know, just tie our shoes and then just go. Like I would get in the car, we'll drive to the trailhead and just start walking. And we would just be gone, you know, for, for, you know, two and a half hours. Then we'd get home and we would make this awesome brunches. Like, I mean, omelets and bacon and,

and pastries that we had bought. Like, so we put this feast, like, right on the coffee table and just start eating, you know? Like, it was just such a, like, a magical Sunday. Like, that was our favorite. That's awesome. I know. But, you know, those are the things that you kind of hold on to. Marta lived in Phoenix for many years, but remember that local TV news expose about her that aired in 2016?

...abc 15 for the story you're about to see. It involves this convicted murderer and his wife, a woman who had an important job in our state and was paid a lot of taxpayer money. Yeah, but not anymore. That's because of... Ever since that aired, Marta has not been able to find work in Arizona. So a few years ago, she moved to Michigan, where her sister lives, and she was able to find a job. Every few months, she flies back to Arizona to visit Jake. She arrives at the prison at dawn.

Visiting hours don't start until 8, but she wants to fill out the paperwork and get processed early so she's first in line. Each time she visits, she walks through a metal detector, gets patted down, walks back and forth in front of a drug-sniffing dog. She rides a little jitney across the complex. And this is like really kind of difficult to explain, but I don't really look forward to it. Like I look forward to seeing him. Right.

But the whole process, just the fact that I have to go through it, it almost feels like you're complicit. You know, like there's actually some legitimate reason why he's still there. The last time she saw Jake was the day after the hearing in his special action.

That hearing where the judge seemed so open to the arguments of Jake's lawyers, asking questions about fairness and equity. The last time I was like very excited because I just went through the hearing and there was a lot of hope. It was the day after the hearing. Right. And, you know, this time it's kind of like, really? Again? Yeah.

And there's like no real end in sight. You know, you can't say, okay, this date, we may know something. We don't know anything.

The end in sight, that checkered flag, even if it's far off, knowing it's there makes the waiting, the time feel so much more possible. The judge's recent ruling changed all of that. Is there any part of you that, I mean, you have a lot more options than Jake does, right? Is there any part of you that saw this and was like, you know what?

Fuck it. I can't do this anymore. Right. And that's the thing. Like, you go through that all the time. And she's just kind of like... I mean, it's hard to explain because it's such a hard relationship to maintain, right?

It's not just that she's in Michigan and he's in Arizona. Not just that he's in prison and she's free. That they can only talk in 15-minute increments. It's also that corrections officials are listening. This call will be recorded and subject to monitoring at any time. And they have used Jake's conversations with Marta against him. Remember the time he told Marta he was angry about being brought back to prison?

And the attorney for the prison system submitted a recording of that call to the board as evidence he was not safe to release? She still, to this day, and completely understandably, and I'm 100% in support of this, is reluctant to share any news about new things she may be looking into.

as far as career paths and things like that because she's afraid that people will turn around and try to sabotage her career and her aspirations in ways that they have before. There are times when...

I am reluctant to share the full depth of my emotional, you know, the texture of my emotional life because that has been used against me. And I'm quite frankly concerned about going to a parole hearing and having a piece of a phone call taken out of context.

So it's these visits, eight hours at a time, every few months, the only time they can talk openly and privately about anything that sustained them. And without an obvious endpoint, they have to be enough indefinitely. You know, when I go through it and I start like getting all this, like, what am I doing? You know, how long is this going to be? Blah, blah, blah. I have to like

go back to the time that we have had together and go back to the times that we're able to talk and, and, you know, actually spend time together and how we enjoyed that time together.

And, you know, the memories and everything. So you have to like, I mean, it's an exercise in just trying to keep that present. Because if not, if you just like not really think about it, you know, there's like no reason why would I continue to do this? Jake says he has faith that sometime relatively soon he will be free again.

He said there have been plenty of times that he put on a brave face and faked the kind of optimism that helps him and his loved ones get through difficult situations. But he's not faking it now, he says. It's real. I mean, you're, you know, you're serving a life sentence. And what if...

What if that's it? What if those nine months were the only nine months you will get as an adult on the outside? I know it sounds like a terrible question, and I'm sorry. I just was wondering if you have thought about that. So, yes. I mean, I've had to face that possibility for over six years now, almost six and a half years now. And...

There is no easy wrapping my head around that. There's no easy way to look at that and just say, well, you know, what is there to do but power through? What is there to do but keep moving forward? What is there to do but focus on the good things in my life, you know, that I have here, the blessings, which are many, um...

Yes, that is the way forward. That is the path forward. But it's never as easy as that. There are moments all the time when I long for the freedom that I had. When I have to remember that

I'll never see my mom again, which is a big part of this. That I may never see my father, my brother, my sister, my wife, my stepchildren, all the people that I love, all the people that I care about, except in a prison setting. And that's a possibility. But I can't dwell on that, Beth. I can't.

Father Stories, that essay in which John Wideman reflects on the fullness of time, is the last essay in a collection called Father Along. It's a book about fathers and sons, about holding your family in great concentric circles of love across generations, about John traveling to the rural South Carolina town where his father's people are from to try to understand something of what it means to be his father's son.

and John traveling to Arizona to try to understand something of what it means to be his son's father.

So many lives and each different, each unknowable, no matter how similar to yours, your flesh and not your flesh, lives passing as yours into the fullness of time, where each of these lives and all of them together make no larger ripple than yours, all and each abiding in the unruffled innocence of the fullness that is time."

The title is a sort of play on the title of one of John's favorite gospel songs, Farther Along. Turns out he misunderstood the title for years. But it also turns out misunderstanding the title helped him understand something he had been after for years. Farther along, we'll know more about it, the lyrics go. Farther along, we'll understand why. Oh, she's up there.

The song is about being patient, accepting that there are things you don't yet understand, and accepting that the more you can be patient, the better position you'll be in to understand when the time is right.

And John reflects in the essay on the fact that one way or another, he would take his place in the long line of ancestors that conspired to make him him and Jake Jake. Being the father of a son who took the life of another father's son with his own two hands. Being the father of a boy who suffered silently, invisibly. Being the father of a son who went to prison a boy and emerged briefly as a man.

is all about holding him with love and patience and knowing that the truth, inasmuch as there is such a thing, would become clear farther along. I don't know if anything has become clearer for the people who loved Eric Kane. I don't want to presume that there was any kind of peace or understanding for them by and by. All we can know is that he's been gone for almost 40 years.

His parents are in their 80s now, too, and his siblings have children of their own. All the things that mattered so much to you were them sinking into a dreadful, unfeatured equality that is also rest and peace.

Time gone, but more, always more. The hands writing, the hands snatching, hands becoming bones, then dust, then whatever comes next. What time takes and fashions of you after the possibilities, permutations, and combinations. The fullness in you is exhausted, played out for the particular shape it's assumed. For a time in you, for you, you are never it, but what it could be.

It's Madeline Barron from In the Dark. I've spent the past four years investigating a crime. When you're driving down this road, I might plan on killing somebody. A rock. A rock.

A four-year investigation, hundreds of interviews, thousands of documents, all in an effort to see what the U.S. military has kept from the public for years. Did you think that a war crime had been committed? I don't have any opinion on that. Season three of In the Dark is available now, wherever you get your podcasts.

I'm Meghna Chakrabarty, host of On Point. At a time when the world is more complex than ever, On Point's daily deep dive conversation takes the time to make the world more intelligible. From the state of democracy to how artificial intelligence is transforming the way we live and work to the wonders of the natural world. One topic each day, one rich and nuanced exploration. That's On Point from WBUR. Be sure to follow us right here in your podcast feed.