“KRAMPUS, THE CHRISTMAS MONSTER” and More Christmastime Terrors! #WeirdDarkness #HolidayHorrors

Weird Darkness: Stories of the Paranormal, Supernatural, Legends, Lore, Mysterious, Macabre, Unsolved

Deep Dive

Why has the depiction of Krampus varied in different movies?

The depiction of Krampus varies because filmmakers often lack a clear understanding of the actual Krampus traditions from Austria. This leads to creative interpretations that differ from the original folklore.

What is the origin of Krampus?

Krampus originates from Austria, where it is traditionally associated with St. Nicholas during his December 5th visits to homes. The creature is meant to punish naughty children, but its exact origins are not well-documented.

How did Krampus gain international attention?

Krampus gained international attention through the popularity of Christmas postcards from the late 1800s, which depicted the creature humorously. Later, the internet and modern media, including movies and books, further spread awareness of Krampus.

What was the impact of the Christmas Eve Mine Disaster in Illinois?

The Christmas Eve Mine Disaster in 1932 killed 54 miners in Moequa, Illinois, devastating the small community. The tragedy left a lasting impact, with Christmas Eve becoming a somber reminder of the disaster.

Who is credited with writing 'Twas the Night Before Christmas'?

Clement C. Moore is commonly credited with writing 'Twas the Night Before Christmas, though some argue that Henry Livingston Jr. may have authored the poem. The true authorship remains a subject of debate.

What happened during the Phantom Choir of St. Albans incident?

In 1944, a teenager named Basil Saville experienced a series of ghostly events at St. Albans Abbey, including seeing hooded figures, hearing bells and organ music, and witnessing a phantom choir. These events were later linked to the abbey's history of ghostly occurrences.

How did the Krampus tradition evolve in Austria?

The Krampus tradition evolved with the introduction of standardized costumes and masks in the early 1900s, followed by the creation of Krampus Runs in the 1980s, which are parades featuring people dressed as Krampus.

- Methane explosion in Moequa coal mine on Christmas Eve 1932

- 54 miners died

- Cause possibly linked to barometric pressure and gas buildup

- The town's long-time Santa Claus was among the victims

- Mine closed after the disaster and never reopened

Shownotes Transcript

No matter how you do self-care, earn cash back with Blue Cash Preferred from American Express. Our benefits don't stop at your pockets. Whether you prefer to unwind by streaming your favorite show, working out, or getting something sizzling in the kitchen, Amex is ready to reward you. So when you're ready to benefit both your wallet and well-being, learn more at americanexpress.com slash us slash explore dash bcp. Terms apply.

Ah, the sizzle of McDonald's sausage. It's enough to make you crave your favorite breakfast. Enough to head over to McDonald's. Enough to make you really wish this commercial were scratch and sniff.

And if you're a sausage person, now get two satisfyingly savory sausage McGriddles, sausage biscuits, or sausage burritos for just $3.33. Or mix and match. Price and participation may vary. Cannot be combined with any other offer or combo meal. Single item at regular price. Stories and content in Weird Darkness can be disturbing for some listeners and is intended for mature audiences only. Parental discretion is strongly advised. In 2015, a new monster started to appear in American horror movies.

a Christmas monster named Krampus. The Krampus's appearance varied from movie to movie. Sometimes the creature was dressed like the Santa Claus of American lore. Sometimes it was just covered in long, white, shaggy hair. But it was always shown with an impressive set of horns sprouting from its head.

In the movies, there is seemingly no agreement about who or what the Krampus actually is, past the common details that the creature is horned, hairy, and somehow associated with Christmas. The reason for this large discrepancy of behavior is simple: the authors of the movies knew very little else about the actual Krampus themselves. You see, the Krampus was not a new monster.

Krampus is in fact a very, very old monster. And how ideas about this monster managed to travel from its native Austria out to the rest of the world and eventually to Hollywood in America is a complicated story. What is depicted now in movies as the Krampus is very different from how the monster started or even how it is currently thought of in its native environment.

Many modern theories and fictional stories connect the monstrous Krampus back to the religious and magical figures of the ancient European past. However, there's no actual evidence of this being true. So what do we actually know about this creature's past? I'm Darren Marlar and this is Weird Darkness. Welcome, Weirdos! I'm Darren Marlar and this is Weird Darkness.

Here you'll find stories of the paranormal, supernatural, legends, lore, the strange and bizarre, crime, conspiracy, mysterious, macabre, unsolved, and unexplained. Coming up in this episode, we're all familiar with the poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas," better known as "Twas the Night Before Christmas." But while we know the poem, we can't be quite as sure about who wrote it.

One of the great and now sadly lapsed Christmas traditions is the telling of ghost stories, something we're trying to bring back here at Weird Darkness. On one particular year, a British teenager took this pastime to a whole other level. He didn't read about a Christmas Eve haunting, he experienced one. The past few years have made Krampus the Christmas Devil a star of the big screen. But have you noticed that every version of him is different than the others?

This may of course be in part to creative license, but it might have just as much if not more to do with the fact that none of the filmmakers had any idea of just what Krampus truly is, what he's all about, and how terrifying he can be. But first: Disaster strikes a small Illinois town on Christmas Eve, stripping away all that was merry and bright for the families who lived there. We begin with that story.

If you're new here, welcome to the show! And if you're already a member of this weirdo family, please take a moment and invite someone else to listen with you! Recommending Weird Darkness to others helps make it possible for me to keep doing the show. And while you're listening, be sure to check out WeirdDarkness.com where you can send in your own personal paranormal stories, watch horror hosts present old scary movies 24/7, shop for Weird Darkness and Weirdo merchandise, listen to free audiobooks I've narrated,

Sign up for the newsletter to win free stuff I give away every month and more. And on the social contact page you can find the show on Facebook and Twitter. And you can also join the Weird Darkness Weirdos Facebook group. Now, bolt your doors, lock your windows, turn off your lights, and come with me into the Weird Darkness...

My school years were spent growing up in a small town in central Illinois called Moequa, and one of the integral events in the town's history was the disaster that occurred in the local coal mine on Christmas Eve, 1932. Almost every family in Moequa was affected by the loss of life at the mine, and even now, more than 50 years later, I had friends whose families had suffered from the deaths of fathers, grandfathers, nephews, and brothers.

Coal had been discovered in Moequa in 1889, and a company was formed to take it from the ground by James G. Cochran of Freeport, Illinois. The Moequa Coal and Manufacturing Company opened in 1891 and within two years was employing more than 50 men from the town. The mine was no stranger to accidents. Four men were badly hurt in an explosion in 1894, and three years later, one died and four others injured in a fire.

By 1899, the Moequa mine was setting new production records, and an electric plant was built near the shaft to illuminate the mine and to supply electricity to many of the townspeople. But more deaths occurred. A portion of a ceiling collapsed on miner Charles Karlosky. Mine superintendent John Carnes was crushed and nearly decapitated when boilers being delivered to the mine shifted positions on a flat car.

In 1905, Thomas Macrae was crushed to death between two mine cars. In 1909, a number of deaths occurred, including the deaths of eight mine mules when an electrical fire broke out. Another man, Stephen Pottsick, was killed by falling rocks. Tony LeCount died of powder burns. Joe Nanny was crushed to death again by falling rock. Jacob Newman died from injuries suffered when the elevator cage fell on him.

In spite of what seemed like one death after another, business at the mine was thriving. The average payroll in 1924 was $10,000, and the average daily output from the mine was about 650 tons of coal. At that time, there were 150 men employed at the mine.

By the end of the 1920s, though, the mine owners began cutting back on the hours and men, choosing to close down over the summer months and rehiring the men in the autumn. This practice was followed until the start of the Depression, when the owners decided that the mine was no longer profitable and closed it down. This was a disaster for the small community. The mine paid the bills for scores of families in town, and there were simply no other jobs to be found in the area.

After much debate, a cooperation was formed by the miners and the townspeople, and money was obtained through subscription to reopen the mine. On September 17, 1931, the mine opened again, this time as the Moequa Coal Corporation. Tragically, though, its days were numbered. The end came for the Moequa mine and 54 of the men who worked under the ground on Christmas Eve, 1932.

At 8:15 in the morning, a methane explosion swept through the mine and killed the men who had just reported for work. Only two men who were inside were spared: the cage operators, whose work kept them close to the bottom of the shaft. The other miners were going towards other areas of the mine to work when they were caught by the explosion.

An exact cause of the disaster has never been determined, but it's believed that an unusual drop in barometric pressure caused gas that was already present in the mine to be forced from the unused areas and into the main corridors of the mine. A spark was probably set off by a miner throwing a light switch or by one of their lamps coming into contact with the gas. Word quickly spread of the disaster, and the mine manager summoned workers from a mine in Pana, Illinois,

The crew arrived in less than two hours, and mine rescue teams around the state were also alerted. Not knowing if any of the men in the mine were still alive, miners from the surrounding area flooded into Moikwa to offer their services. The entrance to the mine had been filled with fallen rock, so they worked to gain access to the shafts and to rebuild the walls that had collapsed. The rescue teams worked continuously through the day and into the night,

On Christmas Day, they discovered a passageway that was littered with the bodies of 12 of the men. All of them were dead, and hope began to dim that any of the miners could still be alive. On Monday morning, 27 more bodies were discovered, and late that night, the battered corpse of Tom Jackson, the town's longtime Santa Claus, was found. The rest of the bodies were brought up out of the darkness over the next several days, with the last being found on December 29th.

The scene at the surface was chaotic. Rescue squads constantly came and went while trucks and wagons moved back and forth near the cluttered mine entrance. The Red Cross set up headquarters at the site and supplied food around the clock. Every newspaper for miles around sent reporters to the scene, and it was estimated that 10,000 people were in the little town during the week after the disaster.

Meanwhile, the families of the trapped miners kept a silent vigil a short distance away, too shocked and stunned to notice the activity around them. The mine stayed closed for six months and then reopened for a short time with cleaning and repair work being done by miners who worked without pay. By December 1933, coal was again being removed from the mine. It remained in operation for two more years and then closed down for good.

There was some talk of opening the mine up again in the years that followed, but it never happened. Eventually, the main shaft was filled, the buildings raised, and the Moequa Mine became an open field on the edge of town. For many years after, Christmas Eve was a solemn occasion, serving as a haunting reminder of a terrible tragedy that occurred in 1932.

Even today, it remains a lingering memory of a dark day during a season of what should have been joy and light. Up next on Weird Darkness: The past few years have made Krampus the Christmas Devil a star of the big screen. But have you noticed that every version of him is different than the others?

This may of course be in part too creative-licensed, but it might have just as much, if not more, to do with the fact that none of the filmmakers had any idea of just what Krampus truly is, what he's all about, and how terrifying he can be. That story is up next. No matter how you do self-care, earn cash back with Blue Cash Preferred from American Express. Our benefits don't stop at your pockets. Whether you prefer to unwind by streaming your favorite show,

working out, or getting something sizzling in the kitchen. Amex is ready to reward you. So when you're ready to benefit both your wallet and well-being, learn more at americanexpress.com slash us slash explore dash bcp. Terms apply. When hiring gets hard, it's easy to fall back on bad habits and turn to gut instinct. That's why Greenhouse brings the best hiring tools together in one platform so you can make the smartest and most fair hiring decisions for your team.

Get access to top talent, create an organized interview plan, and track your progress over time, making it easy to hire the right person for the right role every time. Hire better all together with Greenhouse. Visit greenhouse.com to learn more. No matter how you do self-care, earn cash back with Blue Cash Preferred from American Express. Our benefits don't stop at your pockets. Whether you prefer to unwind by streaming your favorite show, working out,

or getting something sizzling in the kitchen. Amex is ready to reward you. So when you are ready to benefit both your wallet and well-being, learn more at americanexpress.com/us/explore-bcp. Terms apply. In 2015, a new monster started to appear in American horror movies, a Christmas monster named the Krampus.

The Krampus's appearance varied from movie to movie. Sometimes the creature was dressed like the Santa Claus of American lore. Sometimes it was just covered in long, white, shaggy hair. But it was always shown, with an impressive set of horns sprouting from its head. In the movies, there is seemingly no agreement about who or what the Krampus actually is, past the common details that the creature is horned, hairy, and somehow associated with Christmas.

The reason for this large discrepancy of behavior is simple: the authors of the movies knew very little else about the actual Krampus themselves. You see, the Krampus was not a new monster. Krampus is, in fact, a very, very old monster. And how ideas about this monster managed to travel from its native Austria out to the rest of the world and eventually to Hollywood in America is a complicated story.

What is depicted now in movies as the Krampus is very different from how the monster started, or even how it is currently thought of in its native environment. Many modern theories and fictional stories connect the monstrous Krampus back to the religious and magical figures of the ancient European past. However, there is no actual evidence of this being true. So what do we actually know about the creature's past?

The earliest mentions of the Krampus come from the small country of Austria, and specifically from the traditional December visit of St. Nicholas to towns and houses in the country. Nicholas was a Christian monk who lived from 270 to 343 AD and performed many kind acts and miracles in his lifetime. After he died, Nicholas was declared to be a saint, a title that denotes he was especially favored by the God of the Bible and granted special powers to help humanity.

St. Nicholas had earned a reputation for helping children and, sometime after his death , he started making visits to families and children on December 5th each year on the eve of the anniversary of his death. These visits were, and are, mostly so the saint could bring gifts to good children and punishments to bad children, as a reminder to them that good behavior will always be rewarded in life.

Of course, it's unseemly for a saint to punish children, no matter how bad the kids are. So St. Nicholas almost always visited, and still visits, in the company of a number of companions who have the job of meting out any necessary punishments. Though nowadays, these companions mainly just frighten or amuse children.

These companions vary quite a lot across the area of Europe that St. Nicholas appears in. And in Austria, these companions came to be known as Krampus, a group name for a set of ever-changing companions of strange and frightening characters that could come with St. Nicholas either singly or in a group.

In all cases, these Krampusa — the proper plural term for Krampuses — were considered to be under the overall control of St. Nicholas, which was and is often symbolized by the creatures carrying or wearing chains. Not much is known about these earliest Krampusa. Their additional visits with St. Nicholas were very particular to the rural areas of just Austria itself, so not well known outside those areas.

The earliest I've seen mention, a very short mention, of the Krampus as a holiday-related character is in 1825, which isn't all that long ago. A more telling still is that Jacob Grimm, yes, of the Brothers Grimm, in his massive 1835 study of German mythology and folklore, only makes a single mention of the Krampus.

And that's as an alternative name for a different St. Nicholas companion that was better known "necht Ruprecht" or "farmhand Ruprecht" or "servant Ruprecht." So while Krampus was around in the early 1800s, the creatures were not considered noteworthy by those taking notes.

This lack of notation is what has led to so many inventive ideas about the Krampus' past. And while I have no direct reports about the traditions relating to the Krampus in Austria, quite a bit can be inferred from what clues do exist. In the places that celebrate St. Nicholas' yearly visits, many families participate merely by leaving shoes out on the night of December 5th.

Good children will find treats and toys filling their shoes, and not-so-good kids will find a switch that their parents are expected to swap them with. Alternatively, a large number of families in these places, and this definitely included the rural areas of Austria, would actually experience a physical visit from St. Nicholas himself, along with his companions.

These house visits were and still are generally very ritualized. The family would wait for a knock on the door, then lead St. Nicholas and the Krampusa into the room with the family. St. Nicholas would give sweets and small toys to the good children. Then the Krampusa would swat the bad children on their legs with a switch, a warning to correct their behavior before the following year's visit.

These visits undoubtedly were more of an impression on children than just anonymously receiving treats in their shoes, but the saint apparently did not necessarily visit every family, possibly just the ones with problematic children, I would suspect. So some families started impersonating Saint Nicholas and the Krampus themselves to ensure such a visit always came to their house.

Of course, some of you are probably skeptical about the actual existence of St. Nicholas and the Krampusa to begin with. Well, shame on you! While the costume for St. Nicholas was very standardized – big white beard, dressed like a bishop, complete with a big hat and staff – there was no standard idea of what a Krampus looked like. The only requirements appeared to be that any costume created must disguise who was wearing it completely and be as strange and frightful as possible.

Costumes often included old clothes or clothes worn backwards or inside out, animal skins and furs, and anything else that might be available like carpets, horns, animal tails. Faces were blackened with soot, and masks generally just had eye holes. Easy to create and good at hiding the wearer's face.

As I already mentioned, these practices stayed very local to rural Austria for a very long time, and there's currently no good way to determine if any standardized idea existed or developed of what the Krampusse looked like during this time. But in 1898, two big things happened at the same time. First, a very standardized idea of the Krampus was created, and second, the very idea of the Krampus was spread worldwide.

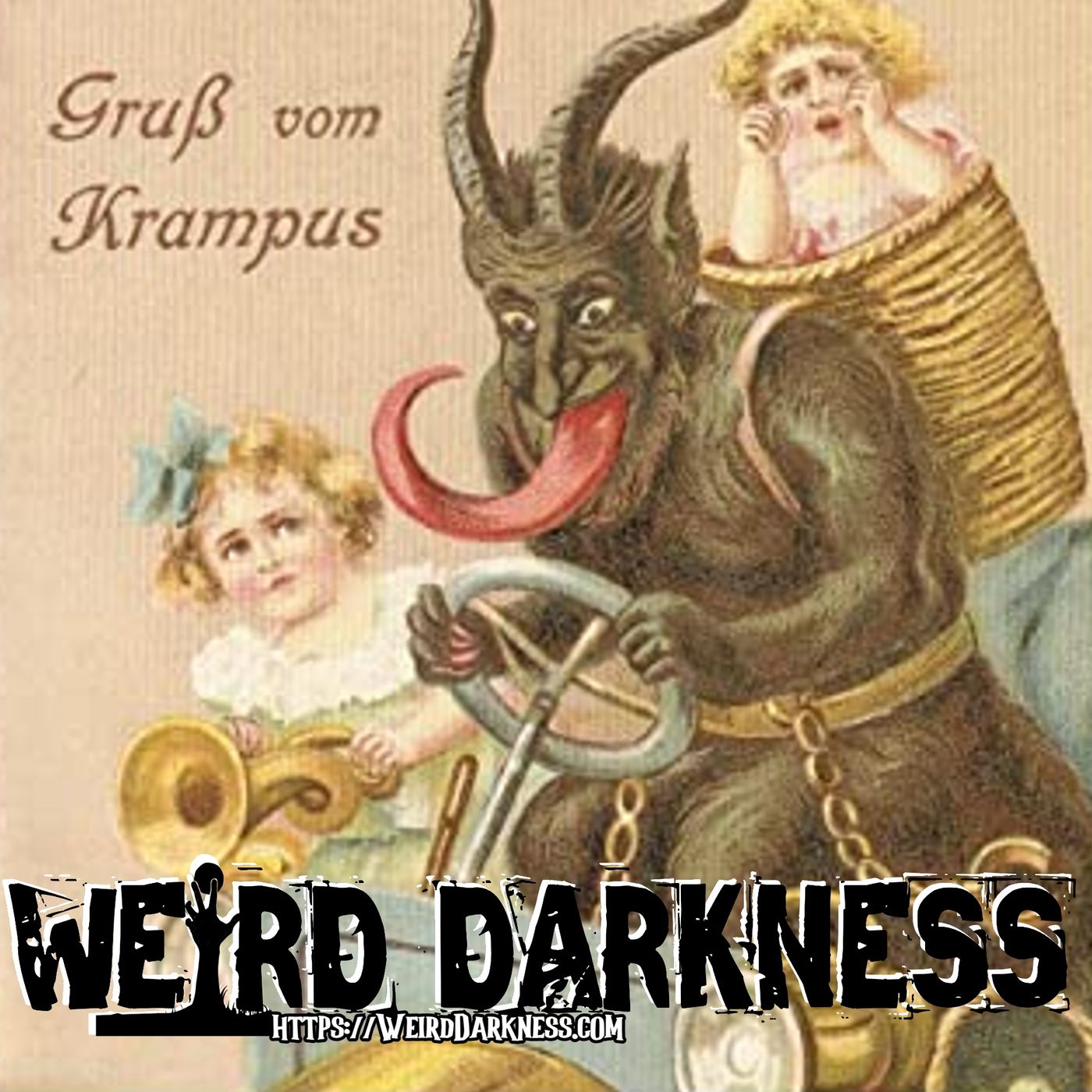

In 1869, the first postal card — a card with pre-printed postage on it, not a postcard — was issued by the government of Austria-Hungary. These were an instant success because they were cheaper to send than a letter, and soon the initially bland postal cards started to support a variety of designs and images, including holiday images during the holidays. The years 1898 through 1918 have been dubbed the "Golden Age of Postcards" by collectors in the know,

And from this time period come some of the most stunning examples of Christmas postal cards and postcards. Within this group of Christmas cards came a new, amusing subgenre sent out from Austria: cards bearing the image of a devil-like figure and the slogan "Gruß vom Krampus" or "Greetings from Krampus." The cards were clearly humorous in nature but presented an idea that was new to the rest of the world.

a monster that participated in Christmas. These cards presented a very distinct picture of Krampus and of the creature's activities, all very different from the rural idea that existed of the creature. It has been speculated this is because the art was being produced by urban artists who were largely unfamiliar with the rural traditions. With an incomplete idea of Krampus, the artists created their own idea of the creature.

The Krampus of the Crispus cards looks like a modified image of the Biblical devil: male with short horns on its head, goat-like legs, a tail, and red skin or fur. Another feature sometimes seen in the cards, as my nephew pointed out, is that sometimes this Krampus has one or both feet replaced with a cloven hoof.

Added to this creature was an abnormally long tongue rolling out of its mouth, and also new was the idea that this Krampus wore a basket on his back, specifically for, as many cards demonstrated, kidnapping naughty children. What was also made clear by the context of the cards was that this Krampus was an individual unto itself. Though sometimes shown in company with St. Nicholas, the creature was now only rarely shown as one of a group,

So, it was THE Krampus, not just a Krampus. These cards were super popular and were collected by some people in the way that baseball or Pokemon cards are today.

But while the cards were being created, an idea of a new monster in the world outside of rural Austria, back in the original home of Krampus, the old traditions and bizarre costumes continued unaltered in all but one way. It seems that over time, more and more people were dressing up like Krampusa for the holiday seasons.

Probably the most important change for the current idea of the Krampusse in Austria itself came in 1930, when sculptor Sepp Lang realized that there was a demand for monstrous masks to be worn by people dressing up as the creatures. Up to that point, masks were very low quality and homemade if they existed. Many people still just relied on anything that would cover their faces, masks or not.

Sepp Lang created monstrous visages from carved wood, paint, and animal hair. Lang produced both wooden masks for performers and full Krampus heads for tourist souvenirs, which meant that by 1930 there were now tourists visiting Austria to, in part, see people dressed as Krampusa.

It's also been stated that early in the 1900s, the bodysuit for Krampus performers became more standardized, leading to actual costumes that would be reused year to year. These new suits were made from the skins of sheep and long-haired goats, creating shaggy bodysuits.

Chains were still favored as part of these costumes, but new to the suits were bells, sometimes huge ones, that would jingle as the Krampusa walked, alerting and warning people the monsters were about. While I have no details about exactly when the bodysuits started to standardize, I suspect it happened about the same time Lange started to add actual faces to the monsters.

Lange died in 1983, but by that time, the creation of Krampus masks had become a national tradition, with many new creators still producing the masks to this day. Lange's masks often included fantastic horns, in imitation of the use of animal horns by the original attempts to dress as the formless monsters.

Langshorns were much larger than those of the Krampus of the postal cards. But the postal card Krampus did have an influence also, as many new Krampus masks feature variations on the lolling tongue of the postal devil.

With all of this interest in dressing up like a Krampus and an ever-increasing number of people who owned costumes, eventually new excuses were going to be needed to wear the costumes. Otherwise, house visits, which still occur, would have one St. Nicholas and a few hundred Krampusa.

So, sometime presumably between Lange's introduction of quality masks in 1930 and Lange's death in 1983, a new tradition developed: the Krampuselof or Krampus Run. These are essentially Krampusa parades, part entertainment, part childhood trauma. People line up along a proposed route to see the run, which is started by a person dressed as St. Nicholas who leads a huge number of Krampusa on the route.

The Krampusa growl, jump, pose and sometimes swat members of the crowd, generally to the cheers of the rest of the crowd. Brave youth will challenge the beasts and sport a bruise as a mark of bravery. These runs are often associated with Christmas markets and can occur any time through December, giving more opportunities for acting troops to strut their monstery stuff.

The earliest printed mention that I've seen of a Krampus run is from 1980, where it was considered a variant on a much older practice called the Perchta run. Frau Perchta is another winter solstice monster, but by no means a companion of St. Nicholas like the Krampus, and mock battles of women dressed as different aspects of Frau Perchta go well back into the history of Austria and Germany.

The newer comparison of the Krampus Run to this older tradition seems to imply that the Krampus Runs might be a very new tradition indeed, dating from just a little before Sepp Lang died in 1983. Interest in the Krampus Runs greatly grew in Austria through the 1990s, and more and more people dressed as Krampusse each year.

Sometime around 2007-2009, there was something of a rediscovery on the internet worldwide of the old Krampus postal cards from the turn of the 19th century. The bizarre images of the clearly devil-like beast scaring and kidnapping children while offering friendly greetings once again caught the attention of a world that had largely forgotten about the beast from Austria.

Websites like Pinterest, interested in pictures but not necessarily stories, spread the old greeting card images far and wide. And soon after, newer sites and books started to explain that the monster was in fact from Austria, and then started to spread pictures of the modern Austrian Krampus runs with their fantastic costumes.

But as new interest grew in Krampus, actual details and legends about its origins were not readily available, as I've said. And in America especially, creative people soon started to make their own stories explaining the monster. The best known of these new fictional tales is a 2012 book by a creator only known as Brom called Krampus, the Yule Lord.

Brahm wove an inventive tale relating the Krampus to Old Norse mythology and painting the creature as an individual character that was seeking revenge for the imposition of the Christian holiday of Christmas over the older pagan holiday of Yule. Krampus is presented as being essentially the enemy of the American Christmas legend, Santa Claus, and unfortunately many non-Austrians now treat Brahm's tale as if it is the correct legendary origin of the Austrian monster.

Since Brahm's book, the interest in the Krampus has spawned new books and movies, as well as new Krampus runs from London, England to Los Angeles in the United States. But make no mistake, the true nature of the Krampus is not in the movies, not in the fictional books, nor even in the postal cards of a hundred years ago. The true nature of the Krampus is well and firmly based in the undocumented past of the folk practices of rural Austria,

where a monster with no known form might still hide. Coming up next, we're all familiar with the poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas" better known as "Twas the Night Before Christmas." But while we know the poem, we can't be quite as sure about who wrote it. That story and more when Weird Darkness returns.

The best-known Christmas poem in the English language begins, "'Twas the night before Christmas, where all through the house not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse." Its history is not only romantic, but there is also a question as to its authorship. The poem was apparently first published December 23, 1823, in the Troy, New York Sentinel.

It was titled "An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas" and it occupied nearly a column in small type and was prefaced with a sympathetic note written by Orville L. Hawley, the editor of the paper, which said:

We know not to whom we are indebted for the following description of that unwearied patron of music, that homely and delightful personages of parental kindness, Santa Claus, his costumes and his equipage, as he goes about visiting the firesides of this happy land laden with Christmas bounties, but from whoever it may have come, we give thanks for it.

"There is to our apprehension a spirit of cordial goodness in it, a playfulness of fancy and benevolent alacrity to enter into the feelings and promote the simple pleasures of children which are altogether charming. We hope our little patrons, both lads and lassies, will accept it as a proof of our unfeigned goodwill towards them, as a token of our warmest wish that they may have many a Merry Christmas.

that they may long retain their beautiful relish for those unbought home-bred joys which derive their flavor from filial piety and fraternal love, and which they may be assured are the least alloyed that time can furnish them, and that they may never part with that simplicity of character which is their own fairest ornament, and for the sake of which they have been pronounced by authority which none can gain say, types of such as shall inherit the kingdom of heaven."

Thus, the first publication of the poem is shrouded in mystery. ***Whether the copy of it was sent in anonymously or whether the editor deliberately falsified in proclaiming ignorance of its source, no one will probably ever know. But the fact remains that the very first sentence of this appreciative editorial comment only serves to render the solution of the problem more difficult.

The poem was used unillustrated as a carrier's address by the Troy Sentinel in several succeeding years and was printed in the Morning Courier, New York City on January 1, 1829. It was again used as an address by the Troy Sentinel in 1830 and apparently was not again reprinted until it appeared in a little volume entitled Poems by Clement C. Moore, LLD and published in 1844 by Bartlett and Welford, 7 Astor Place, New York City.

This book contains a lengthy preface, which begins as follows: "My dear children, in compliance with your wishes, I here present you with a volume of verses written by me at different periods of my life. I have not made a selection from among my verses of such as are of any particular cast, but have given you the melancholy and the lively, the serious and the sportive, and even the trifling, such as relate solely to our domestic circle and those of which the subjects take a wider range.

We are so constituted that a good, honest, hearty laugh which conceals no malice and is excited by nothing corrupt, however ungenteel it may be, is helpful to both body and mind, and it is one of the benevolent ordinances of Providence that we are thus capable of these alterations of sorrow and trouble with mirth and gladness."

"Another reason why the mere trifles in this volume have not been withheld is that such things have been often found by me to afford greater pleasure than what was by myself esteemed of more worth." This evidence of an appreciation of the lighter things of life is an important factor in this controversy because Dr. Moore was a man of serious nature and without reputation as a humorist.

He was born July 15, 1779. His father, Right Reverend Benjamin Moore, was the second Protestant Episcopal bishop of New York. He assisted at the inauguration of President Washington and administered communion to Alexander Hamilton when the latter was dying after his fatal duel with Aaron Burr.

Dr. Moore was educated for the church, became proficient in classical languages, and upon the opening of the General Theological Seminary, of which he was the founder and benefactor, served as a professor of Oriental and Greek literature.

The trend of his mind was distinctly sober and grave. But when it's remembered that Alice in Wonderland was written by a teacher of mathematics, and that nonsense novels and the elements of political science have the same authorship, it may not seem incongruous that the writer of a merry jingle also compiled a compendious lexicon of the Hebrew language, with an explanation of every word in the Psalms.

The combination of grave and gay in literature has happened more than once. The commonly accepted story of the first publication of the poem, while lacking documentary authenticity, is explicit and plausible and has gained credence through frequent repetition.

It relates that Miss Harriet Butler, eldest daughter of Reverend Dr. David Butler, rector of St. Paul's Church in Troy, while visiting Dr. Moore's family in 1822, heard the poem read, copied it into her album, and in the Christmas season of 1823, sent it to the Troy Sentinel.

It has also been printed that Dr. Moore was chagrined over the publication, which he apparently considered quite beneath the dignity of a theological professor, but it is difficult to reconcile this statement with the fact that the poem appeared without affording the slightest clue to its author. Up to the time of his death, July 10, 1862, Dr. Moore was evidently undisturbed as to any future question of his fame, for he had made no effort to substantiate his own position.

He published the poem under his own name in 1844, 21 years after it had first appeared, and on March 24, 1856, he furnished a holographic copy in response to a written request, stating in his letter that, "...I wish the enclosed was more worthy of attention." In 1862, the New York Historical Society sent a representative to interview him.

The report of this agent, published in the Bulletin of the Society under date of January 1919, is disappointing in its lack of detail as to the origin of the poem. Dr. Moore, then 83 years old, did not state that he had furnished the original copy to Ms. Butler but, according to the interview, explained that she had copied the poem from another copy furnished by one of Dr. Moore's female relatives,

He was further quoted as saying that a "portly Rubicund Dutchman" living in the neighborhood of his father's country seat, Chelsea, suggested to him the idea of making St. Nicholas the hero of the Christmas piece, which, he added, had been written 40 years previously for his two children. As a matter of fact, Dr. Moore had three children in 1822. The eldest, Charity, named after her mother, was six years of age. Clement was a baby of two, and Emily was only eight months old.

Only the eldest child could have the slightest interest in hearing about St. Nicholas. The interviewer made no inquiry of Dr. Moore respecting the original draft, which, so far as known, is not now in existence.

Apparently, the original manuscript is not in the custody of the Moore family. For Casimir de Moore, grandson of Dr. Moore, writing in answer to an inquiry says: "My grandfather, Clement C. Moore, wrote it for the enjoyment of his children and had no intent of publishing it. A connection of the family saw it while on a visit to my grandfather, copied it, and had it published anonymously in a Troy paper, I believe,

"There were at once several persons who claimed to be the author, and it was not until urged to do so that my grandfather acknowledged that he was the author. This I have understood from my father, uncle, and aunts to be the facts in the case. I think my grandfather's reputation stands sufficiently high in warranting me in saying that he never could have said he was the author unless he was so in fact. What became of the original manuscript I cannot say."

Although the poem, A Visit from St. Nicholas, is universally known today, it does not seem to have acquired instant popularity. As already stated, it was occasionally used as a newspaper carrier's address, its appearance in 1830 being made memorable by a wood engraving executed by Myron King of Troy in which the children's patron saint and his eight tiny reindeer were depicted levitating over the housetops.

In 1849, Griswold published a second edition of his Anthology of American Poetry in which the poem was included, with credit to Dr. Moore, and a reprint also appeared in The Cyclopedia of American Literature, published by the Deutnicks in 1855. In 1862, it was issued in a separate volume with illustrations by F. O. C. Darley, since which time it has found a place in nearly every school reader, with annual publication as a Christmas feature in a large number of newspapers.

the doubt as to Dr. Moore's authorship has assumed definite form. And this is due to the intelligent and unremitting industry of William S. Thomas, a well-known physician of New York City. Dr. Thomas is the great-grandson of Henry Livingston Jr., who was born in 1748 and died in 1828, residing throughout his life at Locust Grove near Poughkeepsie, New York.

He was a man of distinction, a student, a surveyor, a landed proprietor, a major of infantry in Montgomery's ill-fated expedition into Canada, and so much of a patriot that in his old music book he altered "God Save the King" into "God Save the Congress." Above all, he was a deft manipulator of rhymes, and for more than a century there has been a tradition, or rather a positive belief among his descendants, that he wrote the famous Christmas poem.

Dr. Thomas has attempted to discover the foundation for this belief. Naturally, the effort has been attended with much difficulty, owing to the length of time which has elapsed since the rhyme was written. But the massive testimony which he has collected is worthy of consideration, in the hope that eventually the question of authorship will be definitely settled.

It must be admitted, first of all, that the evidence is purely circumstantial. There is not extant a single written document which shows that Henry Livingston himself ever laid claim to authorship. But this might be explained by the fact that he had been dead 16 years when Dr. Moore's volume appeared. There is no doubt that his family regarded him as the author. And a succinct expression of this belief is found in the letter of Mrs. Edward Livingston Montgomery as follows:

The little incident connected with the first reading of "A Visit from St. Nicholas" was related to me by my grandmother, Catherine Brees, the eldest daughter of Henry Livingston. As I recollect her story, there may be a young lady spending the Christmas holidays with the family at Locust Grove. On Christmas morning, Mr. Livingston came into the dining room where the family and their guests were just sitting down to breakfast.

He held the manuscript in his hand and said that it was a Christmas poem he had written for them. He then sat down at the table and read aloud to them, A Visit from St. Nicholas. All were delighted with the verses, and the guest in particular was so much impressed by them that she begged Mr. Livingston to let her have a copy of the poem. He consented and made a copy in his own hand which he gave to her.

On leaving Locust Grove, when her visit came to an end, this young lady went directly to the home of Clement Seen Moore, where she filled the position of governess to his children.

So well-grounded is the faith of the Livingston family in their ancestors' authorship that as long ago as 1865-1870, when Dr. Thomas' father was teaching in Churchill's Academy at Sing Sing, New York, he had an argument with a grandson of Dr. Moore who was among his pupils, because the latter naturally credited his grandfather with writing the poem.

Again, in 1879, Mrs. Eliza Livingston Thompson wrote that, "...the poem was supposed and believed in our family to be father's, and I well remember our astonishment when we saw it claimed by Clement C. Moore many years after my father's decease, which took place more than fifty years ago. At that time my brother, in looking over his papers, found the original in his own handwriting with his many fugitive pieces which he had preserved."

And Harry Livingstone of Babylon, Long Island not only substantiates this statement, but again refers to the original and accounts for its disappearance as follows:

My father, as long ago as I can remember, claimed that his father, Henry Jr., was the author; that it was first read to the children at the old homestead below Poughkeepsie when he was about eight years old, which would be about 1804 or 1805. He had the original manuscript, with many corrections, in his possession for a long time, and by him was given to his brother Edwin, and Edwin's personal effects were destroyed when his sister Susan's home was burned at Waukesha, Wisconsin, about 1847 or 1848.

There are, of course, some discrepancies in these recorded recollections. If the poem was first read in 1804 or 1805, it could not have been in the presence of the governess of Dr. Moore's children, for Dr. Moore at that time was only 25 or 26 years old and unmarried. A reconciliation of these conflicting statements is suggested by Gertrude Fonda Thomas of Cambridge, Massachusetts, a granddaughter of Henry Livingston. She says that the governess was connected with Mr. Livingston's family,

Another factor in the case is Eliza Clement Brewer, who lived at Rusplayet's adjoining Locust Grove and who married Charles Livingston, son of Henry Livingston. Her granddaughter, Mrs. Rudolph Denig, wife of a retired Commodore of the Navy, states that her grandmother told her that in 1808, while visiting at the Livingston home, she heard Mr. Livingston recite the poem as his own.

When Charles, who had been West, returned in 1826 to marry Miss Brewer, he carried back with him a newspaper in which the poem had been printed and kept it in his desk for many years. In view of the possibility that this newspaper was the Poughkeepsie publication to which Mr. Livingston contributed, a search has been made of the now-incomplete files, but thus far without success, and it is probable that the newspaper was the Troy Sentinel.

The fact that he had the paper and carefully preserved it is a matter of family history. All of these threads of family tradition are tied together with what might be called internal corroboration. Major Livingston left a manuscript volume of poems, many of which were printed in a Poughkeepsie paper and in other publications. The fact that they were all printed anonymously or under the pseudonym R is alleged to account for his failure to publicly claim the authorship of the now-famous poem.

An examination of the 45 productions included in this collection shows that 19 are the same meter as the poem in Controversy. While in Dr. Moore's volume, all of the 33 poems are iambic, with the exception of "A Visit from St. Nicholas" and "The Pig and the Rooster." The Pig and the Rooster beginning: "On a warm sunny day in the midst of July, a lazy young pig lay stretched out in his sty." This is distinctly inferior in theme and treatment to the Christmas effort.

Major Livingston evidently loved the anapestic meter, which Edward Everett says is better adapted than any other measure to lively and spirited subjects. In his connection, there should be mentioned three of his poems. One, a letter in rhyme to his brother Beekman, which begins thus,

To my dear brother Beekman I sit down to write, Ten minutes past eight and a very cold night. Not far from me sits, with a ballancy cap on, Our very good cousin Elizabeth Tappon, A tighter young seamstress you'd ne'er wish to see, And she, blessings on her, is sewing for me. And this conclusion of the carrier's address, written in 1787, And now the end of all of this clatter Is but a small and trifling matter, A puny sixpence or a shilling, From willing souls to souls as willing.

and the tribute which he paid to Nancy Crook, who was a bell in Poughkeepsie where her name is still a treasured memory, and which concluded as follows, "'If a pin or a handkerchief happen to fall, to seize on the prize fills with uproar the haul. Such pulling and hauling and shoving and pushing as rivals the racket of key in the cushion. And happy, thrice happy, too happy the swain, who can replace the pin or bandanna again.'"

These are to say the least in the style of a visit from St. Nicholas. A further examination of Livingston's versifications discloses his delight in the use of such rhymes as clatter and matter, belly and jelly, elf and self, all of which are to be found in St. Nicholas. He was fond of repetitive phrases, such as to the top of the porch, to the top of the wall,

He invariably used the word mama when referring to his wife, while the adverbial use of the word all and the odd usage of gave, occurring frequently both in his verses and the Christmas poem, are cited as additional evidence in his favor. Then further, he was fond of the idea of levitation, while tinnitus frequently appealed to him. In one of his poems, he describes Oberon as riding in a tiny royal coach made of a nutshell drawn by green katydids.

And finally, he repeatedly wove into his lines some references to articles of clothing. Shoes, soft chamois gloves, ruffles, wristbands, new shirts, privates, and even chemises. Just as in St. Nicholas, there's a description of Mama in her kerchief and I in my cap.

Surely, if Livingston did not write A Visit from St. Nicholas, he wrote much that was cast in the same mold. And even if this is all that can be said, it's enough to excite curiosity, to say the least. It recalls the famous observation of Martin Hewitt that two trivialities pointing in the same direction become at once, by their mere agreement, no trivialities at all.

Perhaps this idea was in the mind of Benson J. Lossing, the historian, when he wrote to one of Livingston's descendants as long ago as 1886 that, "...the circumstantial evidence that your grandfather wrote of visit from St. Nicholas seems as conclusive as that which has taken innocent men to the gallows. The circle in which the question has been discussed has been restricted because of the previous unwillingness of Mr. Livingston's family to allow publicity for a belief which has been cherished by them for a century."

The work which has been undertaken, and which is here only partially recorded, is, of course, a labor of love, and has been prosecuted with full appreciation of the difficulty in overturning an apparently established fact. Dr. Moore's authorship, resting upon the inclusion of the poem in his published volume, has stood practically unchallenged, and the burden of disproving the claim of a man of his high attainments and unblemished character is not a light one.

From its literary side, the problem is not without interest. But in a broader sense, the result is immaterial. No matter who wrote it, the poem has been a joy for generations, and it will continue to live as long as the human heart is touched with the spirit of Christmastide. And I will share that poem when Weird Darkness returns. Up next is A Visit from St. Nicholas, better known as Twas the Night Before Christmas, written by... well, I guess it doesn't matter...

Plus, one of the great and now sadly lapsed Christmas traditions is the telling of ghost stories, even though we are trying to revive it here on Weird Darkness. On one particular year, a British teenager took this pastime to a whole other level. He didn't read about a Christmas Eve haunting, though. He experienced one. These stories when Weird Darkness returns.

No matter how you do self-care, earn cash back with Blue Cash Preferred from American Express. Our benefits don't stop at your pockets. Whether you prefer to unwind by streaming your favorite show, working out, or getting something sizzling in the kitchen, Amex is ready to reward you. So when you're ready to benefit both your wallet and well-being, learn more at americanexpress.com slash us slash explore dash bcp. Terms apply.

When hiring gets hard, it's easy to fall back on bad habits and turn to gut instinct. That's why Greenhouse brings the best hiring tools together in one platform so you can make the smartest and most fair hiring decisions for your team. Get access to top talent, create an organized interview plan, and track your progress over time, making it easy to hire the right person for the right role every time. Hire better all together with Greenhouse. Visit greenhouse.com to learn more.

A visit from St. Nicholas, credited to Clement B. Moore.

"'Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse. The stockings were hung by the chimney with care, in hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there. The children were nestled all snug in their beds, while visions of sugar plums danced in their heads, and Mama in her kerchief and I in my cap had just settled down for a long winter's nap."

When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter, I sprang from the bed to see what was the matter. Away to the window I flew like a flash, tore open the shutters and threw up the sash. The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow gave the luster of midday to objects below, when what to my wondering eyes should appear but a miniature sleigh and eight tiny reindeer, with a little old driver so lively and quick I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick.

"More rapid than eagles his coursers they came, and he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name: 'Now Dasher! Now Dancer! Now Prancer and Vixen! On Comet! On Cupid! On Donder and Blitzen! To the top of the porch! To the top of the wall! Now dash away! Dash away! Dash away all!'"

as dry leaves that before the wild hurricane fly, when they meet with an obstacle mount to the sky. So up to the housetop the coursers they flew, with the sleigh full of toys, and St. Nicholas too. And then in a twinkling I heard on the roof the prancing and pawing of each little hoof. As I drew in my hand and was turning around, down the chimney St. Nicholas came with a bound,

He was dressed all in fur from his head to his foot, and his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot. A bundle of toys he'd flung on his back, and he looked like a peddler just opening his pack. His eyes, how they twinkled! His dimples, how merry! His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry. His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow, and the beard of his chin was as white as the snow.

the stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth, and the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath. He had a broad face and a little round belly that shook when he laughed like a bowl full of jelly. He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf, and I laughed when I saw him in spite of myself. A wink of his eye and a twist of his head soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread.

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work, and filled all the stockings, and then turned with a jerk, and laying his finger aside of his nose, and giving a nod, up the chimney he rose. He sprang to his sleigh, to his team, and gave a whistle, and away they all flew, like the down of a thistle. But I heard him exclaim, as he drove out of sight, Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night!

On the night of December 24, 1944, 16-year-old Basil Saville's thoughts were not on holiday cheer. He was not looking out for Santa Claus, but for bombs. The world was at war, and Saville was one of a team of fire watchers. His job was to spend the night guarding the Great Abbey of St. Albans in Hertfordshire, keeping an eye out for enemy bombers and making sure the abbey and its firefighting equipment were in good order.

On this particular night, Saville was left to patrol the abbey alone. Being inside a vast ancient church lit only by moonlight would be an eerie enough experience for most people, but the teen took it in stride. He had spent his life attending the old edifice, so it felt nearly as familiar as his own home. However, an unfamiliar feeling of unease began to creep upon him. Although he did not see or hear anything, he had a nagging sense that he was not alone.

When Seville reached the 15th-century watching chamber, this strange feeling grew more intense. Worse still, he realized this feeling was not unfounded. When he shone his flashlight into the chamber, he saw two hooded figures staring in his direction. When he dashed up into the loft, he saw nothing but two monks' habits lying on the floor. Seville did his best to convince himself that his imagination had merely been playing tricks on him and continued on his tour.

As he was climbing the staircase which led to the roof, he suddenly heard the tolling of one of the abbey's bells. The teen nearly fainted from the shock. All of the abbey's bells had been put into storage on the ground floor. He'd just passed one on his way to the staircase. What was he hearing? He managed to work up the courage to open the belfry door. The tolling had ceased, and the belfry was empty.

After taking a few minutes to pull himself together, Basil began heading downstairs, unaware that the venerable Abbey had a few more Christmas Eve surprises in store for him. The church organ began to play. Saville noticed a candle flickering in the organ loft. "Put that light out!" he yelled to whatever was up there. As he moved closer, he could see the pages of a music book turning and the organ keys being pressed by invisible fingers.

Then, from the direction of the high altar, a phantom choir began to burst into song. As the stunned boy ran towards the high altar, he suddenly saw a procession of monks, led by their abbot, leaving the altar and passing into the saint's chapel. Seville followed them into the chapel, only to find it dark and empty. When he went up to the organ loft, he found an old yellowed music book and a spent candle. So perhaps he wasn't going mad after all.

The book was a copy of "Albinus Mass," an early 16th-century work that Robert Fairfax had written especially for the Abbey. When he returned to the vestry, Saville rejoiced to see that one of his fellow fire watchers had arrived. He'd probably never been so happy to have company in his life. Saville told his colleague about the night's experiences. However, when the pair went to the organ loft, the candle in the book had vanished. Same with the monks' habits Saville had seen in the watching chamber.

that spectral Christmas Eve mass remained the most memorable night in Saville's life. Many years later, he told paranormal researcher Betty Puddick, "I'm not psychic or anything like that, and I've never seen anything like it either before or since. People may not believe me, but I know it happened." For some years, Saville, fearing he'd be mocked, kept his story to himself,

It was not until 1982, when a newspaper published his account as part of a roundup of Christmas stories submitted by readers, that his strange tale became public. Seville, it turns out, was hardly the only one to see and hear phantom church services in the Abbey. There were reports from the 19th century of people hearing a ghostly organist during the night. Numerous people have seen the ghosts of Benedictine monks in and around the church.

Robert Fairfax had been organist and director of the Abbey Choir for many years. He is acclaimed as one of the greatest English musicians of his time. In 1921, to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Fairfax's death, his albinous mass was performed in the Abbey for the first time since the great composer's death. Well, performed for the first time by living musicians at any rate.

One Frank Drakert told Betty Puttick of a conversation he'd had with Cannon Glossop, who lived near the Abbey, the morning after the concert. "Did you enjoy the Fairfax music last night, Cannon?" Drakert asked. "Yes," the Cannon replied. "But you know, Drakert, I had heard it before." He went on to explain that on more than one occasion he had heard that very music coming from the Abbey in the middle of the night, at times when he knew there was no human choir inside.

The monks and musicians of St. Albans clearly loved their church and see no reason to leave it, just because they happen to be long dead. Thanks for listening! If you like the show, please share it with someone you know who loves the paranormal or strange stories, true crime, monsters, or unsolved mysteries like you do.

You can email me anytime with your questions or comments at darren at weirddarkness.com. Darren is D-A-R-R-E-N. And you can find the show on Facebook and Twitter, including the show's Weirdos Facebook group on the Contact Social page at weirddarkness.com.

Also, on the website you can find free audiobooks that I've narrated, watch old horror movies with horror hosts at all times of the day for free, sign up for the newsletter to win free prizes, grab your Weird Darkness and Weirdo merchandise. Plus, if you have a true paranormal or creepy tale to tell, you can click on "Tell Your Story." All stories in Weird Darkness are purported to be true unless stated otherwise, and you can find source links or links to the authors in the show notes.

The Christmas Eve Mine Disaster was written by Troy Taylor. The Christmas Poem That Started a Feud was written by Henry Litchfield West for Victoriana Magazine. Krampus the Christmas Monster is by Garth Haslam for Monsters Here and There. And the Phantom Choir of St. Albans is from Strange Company. Again, you can find links to all of these stories in the show notes. Weird Darkness is a production and trademark of Marlar House Productions. Copyright Weird Darkness. And now that we're coming out of the dark, I'll leave you with a little light...

Matthew 1:23: "The virgin will be with child, and will give birth to a son; and they will call him Immanuel, which means 'God with us.'" And a final thought from Norman Vincent Peale: "Christmas waves a magic wand over this world, and behold, everything is softer and more beautiful." I'm Darren Marlar, thanks for joining me in the Weird Darkness.

This season, give the gift of the Virginia Lottery's Holiday Scratchers to all the adults in your life. But don't forget to play the Holiday Online Games and New Year's Millionaire Raffle for even more excitement this season. Play in-store, in-app, or online.

I give scratchers to my boss and I give scratchers to my wife. I give Virginia Lottery holiday games to every adult in my life. I give scratchers to my yoga instructor, my mailman, and my friends. With the lottery's New Year's millionaire raffle, the possibilities never end. And when I need some time alone to keep from going insane, I open up the lottery app and play the holiday online games. The best way to bring joy all season long and be a gifting MVP is giving holiday games from the Virginia Lottery.