Finding relics among the ruins of the Cultural Revolution — with Ian Johnson

Peking Hotel with Liu He

Deep Dive

Why did Ian Johnson initially choose to study Chinese?

He took Chinese as a lark, influenced by his father's work with a Hong Kong company and the growing interest in China after diplomatic relations were normalized.

What was Ian Johnson's experience like during his first trip to China?

He spent six months at Peking University, realizing his Chinese was poor but gaining valuable experiences, including teaching English and witnessing remnants of the Cultural Revolution.

How did Ian Johnson's approach to journalism in China differ from other correspondents?

He aimed to spend one week every month traveling outside Beijing, avoiding the news cycle prison and focusing on grassroots stories rather than copying other journalists.

What was the impact of Ian Johnson's journalism on China?

His work had minimal direct impact on China, as it was rarely read by Chinese citizens, but it contributed to documenting human rights abuses and other issues.

How did Ian Johnson choose his topics for reporting in China?

He focused on big themes and case studies, often working on multiple topics simultaneously and opportunistically finding relevant stories to fit his themes.

What did Ian Johnson regret not reporting on during his time in China?

He regretted not interviewing Liu Xiaobo, a prominent dissident, and not focusing more on public intellectuals in China.

How did Ian Johnson's perception of public intellectuals in China change over time?

Initially, he viewed them as less important, but later realized their significance, leading to a series of Q&A articles and ultimately his book 'Sparks'.

- Exchange student at Peking University in the 80s

- Lingering effects of the Cultural Revolution

- Challenges of foreign journalism in China

- Tendency of journalists to copy each other

Shownotes Transcript

Hi, listeners. Welcome to Peking Hotel. I'm your host Leo.

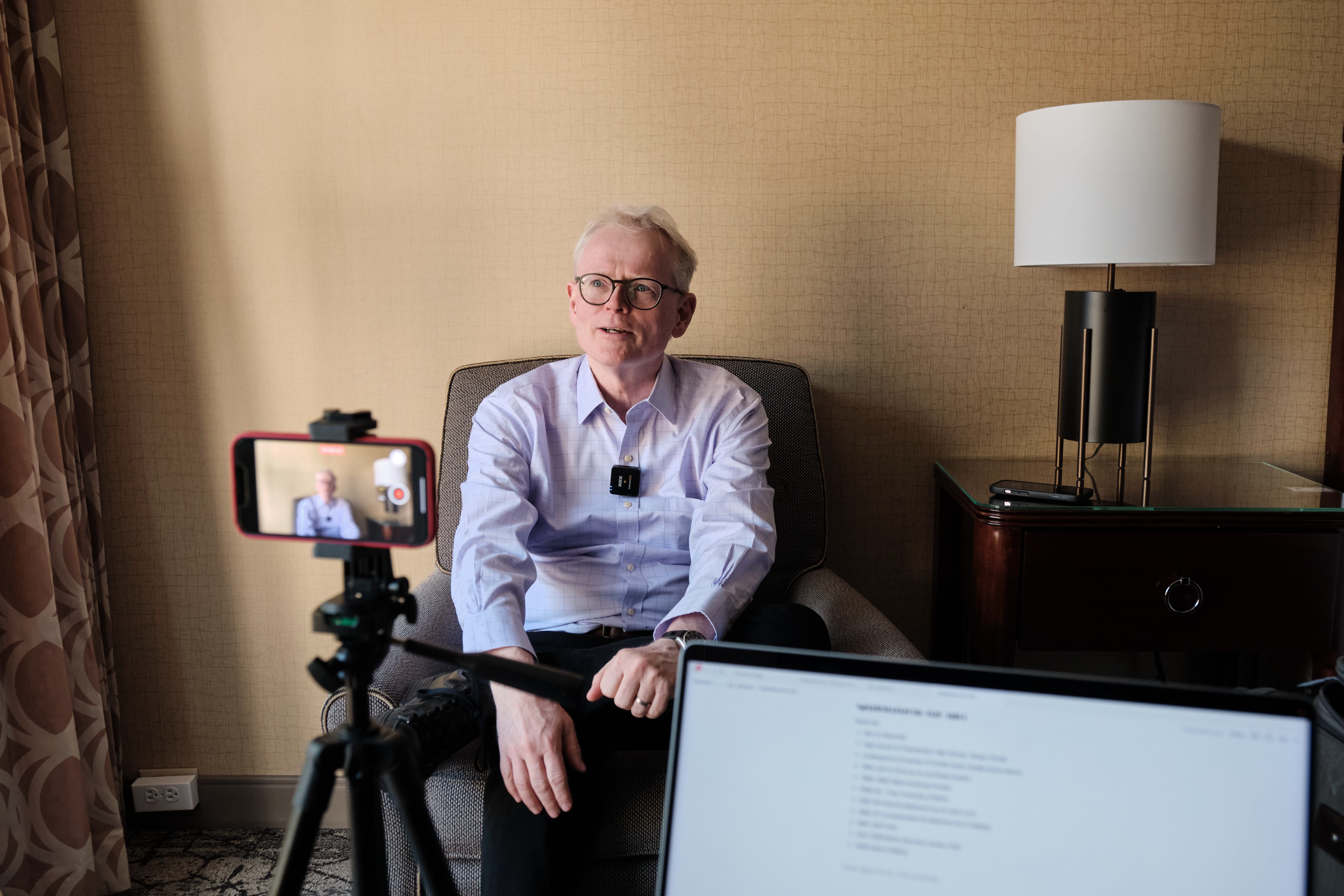

This is an oral history podcast that tells the personal stories of China specialists. Ian Johnson is a Pulitzer-winning journalist. He began his career as a graduate student at the fall of the Berlin Wall and has since worked for the Baltimore Sun, The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and the New York Review of Books. He has written multiple books on religion, including Wild Grass: A Mosque in Munich and Souls of China.

His latest book, Sparks, tells the story of the underground counter-history movement in China. And I am inspired by Ian's dedication to telling the stories of the Chinese civil society where idealistic individuals work creatively to advance social justice and resist the repressive state.

This episode tells Ian's own story from his first trip to China to his journalistic practices with regard to China. And without further ado, let's dive into it. Thank you for coming, Ian. Yeah, no problem. My pleasure. I was reading your first trip to China, a fascinating story of being an exchange student at Beida in the 80s.

Could you narrate a little bit of that story? I mean, you've written about it, but just in terms of your own words now, how would you describe that trip? Yes, I didn't intend to study Chinese at university. I went to the University of Florida for not any particularly good reason except my girlfriend was going there. And then I thought, "Oh, I probably would like to be a journalist," and they have a good journalism program. So I convinced my parents, who thought I should apply to other universities, and said I went there.

And then they had a language requirement and the language requirement... I didn't want to take another European language. I grew up in Montreal and we had just moved to Florida when I was in high school. So there was an ad that a teacher put up on a bulletin board, like a real old-fashioned bulletin board actually saying looking for students to fill out a class in Chinese. And I decided to take the Chinese as a lark.

for fun. I guess in the back of my mind a couple things were happening. My father worked for the Hong Kong company Swire

Tai Gu Group. Yeah, Tai Gu, right? And they own Cathay Pacific and their big shipping company and real estate company and so on and so forth. And so I thought maybe he'd been to Hong Kong a few times, so maybe that was in the back of my mind. Also, this was the time just after diplomatic relations had been normalized in the late 1970s and the first wave of books were coming out by foreign correspondents like the husband and wife team of Linda and Jay Matthews who wrote a book called

called One Billion, Fox Butterfield, Alive in the Bitter Sea, Bernstein's From the Center of the Earth,

the Earth or from the center of the world is anyway this book on about China they all wrote these books on China after I've been there for a couple years so I thought yeah maybe I'll take Chinese for fun I was always interested in other cultures and stuff like that and I had a fantastic Chinese teacher he made Chinese a lot of fun and he was a very gifted linguist and wrote a great grammar of Chinese and so it became like this puzzle and then I I knew from my

My experience growing up in Montreal, and this is at a time of a lot of tension in Quebec, in Canada, over language. It led to a terrorist movement and almost a separation of Quebec from Canada and so on. So I knew the importance of language and being in the environment, that you really only learn a language efficiently if you're in the environment. So they had an exchange program

to Beijing and I went to Peking University, so I went to Beida and spent six months there. And I realized how terrible my Chinese was at that time. But it was a great experience nonetheless. In hindsight, at the time when you're living in something,

especially when you're a younger person, you think that something that happened five or six years ago or ten years ago is ancient history. But in fact, most people have experienced that in society. And the Cultural Revolution had only just ended, really, '84. The Cultural Revolution just ended six years ago. So I

I experienced that in many different ways. I was asked to teach English at a school. I went there and I had students write essays, you know, the way you normally do. And one student wrote like a 10 or 15 page essay about her experience as a sent down youth.

And I'm not as smart as somebody like Peter Hessler, who probably could have written a whole book around this. I was like, oh my God, like, this is amazing. It's also kind of sensitive. So I corrected the grammar in the essay and then I sent it back to her. And, you know, instead I probably should have photocopied it and, you know, like later written an article or something.

Anyway, I wasn't that clever. But I had these kind of experiences. There was some guy who befriended us, who claimed to have been related to Puyi, the last emperor. Probably nonsense, but he was clearly a little Pogoloko, like a little crazy, a little Shenzhen Bing, probably from the Cultural Revolution and all that. He became a great friend of ours, rooming with a person who went on to become a noted Chinese political...

political scientists of China, Chris Reardon, who is now at the University of New Hampshire. And Chris was a great roommate. I was with mostly older students who were there through the Committee for Scholarly Communication with China, the CSCPRC. And they sort of took me under their wing and we went bicycling all around the place. Because there was

very little in a way of subways in Beijing then, just two lines and the buses were terrible. And so we biked everywhere and we used this guidebook

called NAGELS, N-A-G-E-L apostrophe S. They published these books that are called encyclopedias, like travel guidebook encyclopedias. They're kind of small, compact, but very fat. And so they would have like a whole section at the beginning of Chinese philosophy and Chinese history, and they'd go through and tell you what all they've done. It's meant, I think, for somebody to sort of read on the airplane flight over, or more like a ship...

a ship, you know, a trip over because they were like really thick. And then they would have like major things in each city. Then they had fold-out maps like of the Forbidden City. And this was compiled in 1964, I think primarily by French diplomats. And then it had been reprinted around 1980 when China was opening up again. And it was a great book to have, a great guidebook to have because it showed the Beijing before the Cultural Revolution.

So it said, like, going to Wu Ta Se, the five pagoda, like, temples, five tower temple. And it still exists. But when we went there, it's like a big platform with five, like, towers on the top, I think, right? And they were all smashed and destroyed. There were tiles everywhere. And it's sort of behind a factory gate entrance.

Now if you go there, the whole thing's been cleaned up, it's a park, they've rebuilt everything, you wouldn't know anything had happened. But back then you could still see these signs of the Cultural Revolution and we only knew these things existed because they're in the guidebook.

Because if you're just driving down the street, riding your bike down the street, you wouldn't have noticed it because other stuff had been sort of built in front of it. So that was a great source of information. We also traveled around. We made trips to Datong and Luoyang and Xi'an and then also I went down to Hangzhou, Suzhou.

These are the time of really slow trains, you know, with the hard sleeper. But it was a great chance to talk to people and learn more Chinese and so on and so forth. So it was a good experience. On that trip I wrote my senior thesis for college. I ended up majoring, doing an interdisciplinary degree in journalism and Asian studies. And I wrote about foreign journalists in China.

So I still have that thesis actually. It's not the world's greatest senior thesis, but it's actually okay. I interviewed all the journalists who were there. I did it on North American journalism in China after '49 because

American newspapers couldn't be in China, but there was the Toronto Globe and Mail which had a correspondent there through the 50s and 60s and 70s. So I talked to like the New York Times correspondent at the time was John F Burns who had been a correspondent for the Globe and Mail sort of ten years before that and I talked to them about their all their experiences the limitations the problems they had and I noticed that

Something that really affected my work later was that journalists tend to copy each other a lot. There's a lot of sort of, I don't think copycat, maybe a little wrong, but you know, me too-ism, like, oh, you're doing that, I'll do that too, and always trying to match somebody else. And part of that back then in the early 80s was that it was hard to travel around China. It was hard to get interviews. It wasn't

It's kind of like it is now in the 2020s, but later it became much easier to do work in China in the 1990s and the 2000s, which were kind of a golden age. But back then, if you could only go to Beijing and Tianjin,

without government permission. So you could go to Tianjin without government permission because that was the harbor, so they kind of thought, "Okay, foreigners have to go to the harbor to get their stuff from ships." And you were allowed, there's a small strip of land between Beijing and Tianjin, Hebei, right? There's a bit of Hebei there, and you were allowed to go on that highway. But you weren't allowed to just like go off to Zhangjiakou or take a train to Shijiazhuang or something without permission.

So, journalists had a hard time getting out and talking to people. So, somebody said, you know, there was, say, a profile in Renmin Rabao of a successful farmer, a 10,000 Hu, you know, like they called them millionaires, but they just had earned 10,000. Wanyi Hu. Wanyi Hu, yeah. So,

Everybody was like, "Urgh, go interview that person and I'll write the same story." Oh, so they were actually matching people's daily. Well, that's how they knew about it. And then matching each other. Yeah, first they were, I mean, that's how they'd get information, maybe from China Daily or something. Maybe somebody heard about it.

But then, "Oh, she did that? Well, I'll go do it too." And I had sympathy for them, but I noticed this is actually a phenomenon, not just in China, but it's became a phenomenon again, especially in the Internet age when everybody is watching each other on Twitter and your editors are watching you and then they're saying, "Oh, so-and-so had a story about this riot in Xinjiang. You have to write it too."

I criticized that in my senior thesis and I vowed if I were ever to go back to China as a correspondent, which was my goal, that I would not do that. And I guess that informed how I viewed what being a correspondent was. I wanted to

Well, I had sympathy for the restrictions that they were under. I didn't want to do stuff like that. I wanted, if at all possible, to get out and talk to more people and break out of the news cycle, which is really a prison because you end up just copying each other. So, yeah, that was my first trip to China in 84, 85.

And then after that I realized, "Boy, my Chinese is crap." So I then went back to Florida, graduated, got a job to pay off some college debts. I worked at a local newspaper in Orlando, Florida. And then my teacher, the guy I really liked, Dr. Chu, he's Taiwanese. He was like a Y-Sheng Ren from Taiwan. And his classmate ran this thing at Taiwan's Shifan Daxue.

the Taiwan National Normal University, they have a thing called the Mandarin Training Center, the 國語中心 . So I went to Taiwan in '86 and stayed there for two years. And I think that's when I really kind of learned Chinese, because I've

It was much more intensive. It was two years. And I think one theme throughout your journalism career was this focus, this attention on the Chinese underground society, the churches, the underground historians, the civil associations, the civil society that the government...

not only refuses to recognize but also from time to time repress. And it seems that even from your very first trip you were looking for that underground society but looking at Nego's guidebook and finding out old temples that had been smashed up that people didn't really know about and sort of padded over by other bits but if you did look closely enough you could discover them.

How would you describe your interest in the underground China? One that you came to write a lot more about much later, but you seem to have a consistent interest in. Yeah, you could say underground or grassroots is maybe the thing I think of the most. I guess I wasn't so interested in...

intellectuals in Beijing and their disputes and discussions and in some ways that was a pity because I was in China from 1994 to 2001 as a correspondent during my first stint as a correspondent

And I never interviewed Liu Xiaobo, right? Of course he was in and out of jail, he was under house arrest a lot. But he would have been somebody, later I realized that was a bit churlish of me too. But I kind of felt like the intellectuals in China didn't seem to reach

and didn't really have good explanations for society because they didn't really interact with a lot of society. They played the role of the loyal critics of the government. You can see this in the scar literature by these people who had experienced the Cultural Revolution and they were almost more upset that they had been victimized.

because they wanted to victimize other people. I'm the loyal, I should be talking to the emperor. I should be the one in charge. Instead, I got impressed. I mean, I got suppressed. Concern for the country, concern for the people, sort of thing, which is often kind of just self-serving bullshit. So it wasn't...

I wasn't so interested in them. I thought there was more. I also just thought China is such a big country. It would be like if you spent all your time inside the Beltway in Washington. Say you were a U.S. correspondent and you spent all your time inside the Beltway, you would have a really warped view of the United States, right? If you'd never been to the Mississippi Delta, if you'd never been to Texas, if you'd never been to California,

or whatever, you know, you go on and on and on. But it was similar in China. It's a similar sized country. So I thought my role was to get out of Beijing. And I had a rule when I went back as a correspondent that I would try to spend one week every month traveling outside of Beijing, which maybe that doesn't sound like a lot, but it's actually a lot. Because when you try to logistically organize it, it means that you come back, you write your articles for a week, and then you're already planning your next trip. And you've got to

especially in the 1990s it was harder because the logistics weren't so easy and then you'd have to plan your trip, you'd have to get permissions and stuff like that to do it. I did do that quite a bit and it got easier and easier to do that.

because China's infrastructure got better, it wasn't so hard to fly places, the trains of course later got really good, and by the late 2000s, early 2010s, it was really easy to work in China and to go to the grassroots. I rented a car, you know, it was like no problem to rent a car, you could fly into Nanjing or someplace like that and there'd be a Shenzhou car rental place there on your app and you just ding-ding-ding, go get the car and drive off and do whatever you want.

So it became progressively easier. How do you go about reporting in China? I never wanted to be one of those reporters that worked with the translator. Some people make a whole career out of writing about places.

Books and stuff like that about places where they can't communicate with people directly. They have to always work through translation. I couldn't imagine doing that. Like I just feel you lose the nuance. It's also terribly inefficient because you're going through a translator all the time. It's like, you know, you have an hour conversation, but really you only have half an hour because half of it's this translation. You can't know every language in the world, but I think we should have more

professionalization in a way and I think it would be better like that model I think it's pretty much dying out anyway the model of the big expat correspondent who would go from London to Paris to Moscow to Beijing to Tokyo and then retire or something like that that's kind of dying out one thing was like really expensive and these people just don't have money for that but it was also led to this kind of neo

imperialist view like here I am arrived in Beijing, where's the silk market so I can go buy some funny toys to take home to my family or where can I you know where is this and that and you know

They don't have any interaction with Chinese people. When I was there in the 90s, there were still a lot of people like that. They basically only spent their weekends with other expats and stuff like that. They weren't bad journalists. I mean, they were professionals, but they were not really hanging out with Chinese people. And I think the main thing was just that I didn't... This is also why in the souls of China, I don't have stuff on minority religion. I don't have anything on Tibet or Xinjiang.

because I felt that A, it would be too much. These are kind of really separate cultures. And if I'm going to delve into all of that, the book was already long enough. It would get even longer. It's not meant to be an encyclopedia. And it was enough to do the 1.3 billion Han Chinese people without the 100 million Chinese.

minorities but another key reason is I don't speak Tibetan or Uyghur and so I felt like it would be hard to I didn't want to have to work through translators and stuff like that. And how did you pick your topics? I was lucky because early on in the 1990s I worked for two publications

that were the opposite of, like, the New York Times. The New York Times is the paper of record, you know, and, like, if Liu Xiaobo is detained or something like that, you've got to write an article about it. If something happens, you know, the premier lets out a fart, you've got to write about it. You've got to kind of match the wires, and your editors are always, like, asking you to do that. But I first worked for the Baltimore Sun, which was a local newspaper where they had a grand tradition of, I had the first foreign correspondence in America.

Now it doesn't have any foreign correspondents, like all regional newspapers in the US. But back then it had eight in different bureaus around the world. And they told me, we don't want what's on the wires.

We can get the wires. Don't give us the stuff that's on the wires. Go travel. Tell us what it's like in China. People are not... And so I was sort of friendly with the guy from the Washington Post. And he often, if the foreign minister said something, the Washington Post had to report it. The New York Times, they were always competing for these kinds of scoops and stuff like that. I didn't have to. I could just go off and do stuff. So it was kind of fun.

And then later I worked for the Wall Street Journal. And the Wall Street Journal, which I joined at the beginning of 1997, they had an explicit policy that we are a second-read newspaper. So we are, everybody has their hometown newspaper, like the Houston Chronicle or the Kansas City Star or the New York Times or whatever, and they read the Wall Street Journal when they get into the office. And so we don't want to have stuff that's in those papers already.

So, and they had a very good editing staff back then. They got rid of all that later after Murdoch bought it and they just kept cutting and cutting the newspaper. But they used to have a staff where you had to write these long, where you were allowed to write these, encouraged to write these long articles that were well researched and edited by many people and they always had to be kind of exclusive.

Like, in other words, they didn't want it. If it had been in the New York Times, you could have worked on something for a month. And if the New York Times did a kind of Chao Bu Duo, half-assed version of the story, they would say, sorry, it's killed. It was like sometimes crushing when that happened. But that was a great experience because it really encouraged us to do something different. And also, you know, looking at China through the economic lens meant that it was also in some ways less

like we were not viewed as sensitive by the government. They kind of had this equivalency. They thought the New York Times was like People's Daily and they said the Washington Post is like Guangming Rabao and you are like Jingji Rabao. It's like, okay, who reads Jingji Rabao? Anyways, but it's like the economic newspaper. It's less ideological. Less ideological. We're just writing with the economy, which back then was like a good thing. It's opening up. China wants to be part of the world economy. And so we were welcome.

And that meant that when I was writing later on Falun Gong for the Wall Street Journal, they didn't pay any attention to me. I remember at the height of the Falun Gong protests in downtown Beijing, because it went on for like a whole year, people protest, protest, protest. I was going for a walk with Charles Hutzler, who at the time was the AP Bureau Chief,

and he was with his kids, and there were these plainclothes policemen behind us. I'm like, oh, I wonder who they're following. So Charles said, let's go check. So he went this way with his kids, and I went that way, and they followed him. I thought, he's got his kids with him. What can he be doing that's interesting? In fact, I was going to go meet somebody from Falun Gong. He was just taking his kids to the playground, but they were just so fixated that AP is like Xinhua in their equivalency mind.

So, yeah, we were not as paid as close attention. Where did they get that idea from, that sort of equivalence that New York Times and People's Daily and... This is what Chinese journalists tell me. They're all joking about that. And I said, I don't know if it's exactly true, but they did view it as a less sensitive paper. And, you know, probably overall we...

We weren't always writing about human rights. The New York Times basically was always writing about human rights. And it was one of the problems, I think, with the foreign reporting is that even when things were pretty good in China, journalists, I wrote an article about this for the New York Review of Books, but journalists are trained to only find the bad, right? They always say, like, the bridge that collapses is the news. The bridge that doesn't collapse is not news.

And I understand, especially for a local newspaper, if a bridge collapses, it's news, right? For sure. But in a developing country like China, which is building bridges all the time, and infrastructure is a big thing, actually the bridges that they're building is kind of a big story. And I remember having that conversation with a member of the foreign ministry who

In '94, after getting there, I went on a trip. They used to organize these trips, MOFA did.

and we went to Guizhou to look at the poverty alleviation. And this guy asked me that question, he says, "Why do you journalists, why look at all these bridges that we've built here? Why don't you write about this?" I'm like, "Ha ha ha, so silly and naive you are. That's not a story. That's just a bridge, so what?" I said, "Yeah, it's one of the collates. It's not dog, what is it, dog bites man, that's not news. Man bites dog, that's news." So it has to be something unusual. But later I realized I kind of got it wrong, because in effect,

He had a point. These bridges, all that infrastructure, it was what helped lift many people out of poverty. The infrastructure that they were building, these roads and stuff like that, it had a huge impact economically. But we didn't really write about that. So I thought sometimes it was working as a journalist...

Yeah, working as a journalist was good. It's a mixed bag. I think working in a foreign country, it can be misleading to readers. Because if you're working for the Palo Alto Daily and you write about a bridge collapsing,

The readers know most bridges in Palo Alto have not collapsed and this is an unusual situation. But if you're writing about China and it's a series of catastrophes, this guy got arrested, that thing happened, there was an earthquake, blah blah blah. People back in the United States think, "Wow, China's really fucked up, right? Like, look at all that shit happening." And then you don't realize that actually, you know, millions of people are lifting themselves out of poverty, hundreds of millions of people, the country's roaring ahead economically,

People would come to visit sometimes in China, you know, friends and relatives, and they'd say, "Oh, it doesn't look like I thought it would look like." They thought it would look like Soviet Union or in the middle of the Cold War or North Korea or something like that. And it was kind of pretty relaxed. I mean, it wasn't that—of course there were human rights violations, lots of problems, like Falun Gong. But it was often, as a foreign correspondent, it was a weird feeling that

you know, you're not, you really need to be more of a sociologist to write about a country or an anthropologist rather than being this hard-nosed, driven journalist. But, you know, what did I get a Pulitzer for? I didn't get a Pulitzer for writing about bridges being built. I got a Pulitzer for writing about people being beaten to death for Falun Gong people being beaten to death by police. So, you know, that's what you get the rewards for in your profession. I guess the, the, uh,

The normal expectation of journalism everywhere is to write about bad news, is to write about wrongs that have been committed so you would correct for the sake of justice. That's what they always say in the Pulitzer. Part of the Pulitzer submission or any prize submission is what was the impact of your article. So they want you to say, I did a series about bridges in Palo Alto after this one bridge collapsed. I saw that 25 bridges were in bad shape and the

The state government passed a new budget, extra budget based on these articles to rebuild the bridges in Palo Alto. Oh great, that's what we want, you know, impact. Right, that's what all these foundations and stuff want. But the reality is that when you're writing about a foreign country, you're also kind of interpreting, you're supposed to be giving a picture of what's going on in the whole country. You're supposed to be giving a picture of what's happening in this country.

I think. I still wrote mostly negative stories. I think, like, on some level, that is a contradiction, a problem, I think.

two directions I want to go from here. One is how did you decide what stories you wanted to pick up since you didn't want the mainstream stuff, you didn't want whatever your colleagues were writing about the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the New Statement, the US-China relations. You wanted to find out about the real China, the one that's hidden, that's

waiting there to be found as a piece of gem. But at the same time, there's plenty of praise around for China. If you just look at People's Daily, Guangming Ribao, the official propaganda machine, and of course all that happened, all the reporting that happened before the rise of the private media in China.

news was pretty biased in the direction of being favorable to the Chinese Communist Party in China. So the fact that there were foreigners coming in, criticizing, finding out which bridges actually did burn and which buildings did collapse and which officials did collapse

corrupt and killed a bunch of people. That's actually good service for the Chinese media consumers, perhaps less so for the foreigners. So I wonder, I mean you can take turns to answer these questions. How did you pick your stories and what do you think of your reporting to the Chinese consumers?

Well, the weird thing about being a foreign correspondent in a place like China is your work has

zero, basically zero impact on China, except maybe in some way, abstract way, but it's never read by the people. You know, my first job, like I mentioned at that paper in Orlando, I was in a community that had, it wasn't a city, it was a community in the county, it was like a giant subdivision, and I was like the only reporter on there, and they had a meeting once a month with the county officials, and they decided stuff like what roads are going to be

People took that really seriously. They had an advisory council. I was like the only guy that reported on it. When the article would come out the next day or the day after, people would call me up. You know, this had a lot of retirees there. These are like ex-World War II military guys. And then they treated me like their kid. They said, listen, you got this a little bit wrong. You know, this article, you got that number. It's not exactly like that. The tax rate is not 2.3. It's 2.2. And you got...

But that's pretty good and you'll get it right the next time. You got like immediate feedback. You couldn't write any bullshit. And people can go to any foreign country and kind of like make up shit. They know, oh, I talked to old Wang and he told me he hates Xi Jinping. Like who's old Wang, right? It's like you don't even know Wang Jun. You just call somebody Wang Jun. There's like 10 million Wang Juns in China. And so I think there's like a lot of, it doesn't encourage good journalism.

there's a lot of stuff i i saw a colleague at the new york times who just made up he wrote stories

based on cut lines that photographers, so a photographer would go out and take all these pictures and write the cut lines, and then he wrote the article as if he had seen this himself, but he hadn't. He was just rewriting the cut lines into an article. And finally the Times had to take some measures against that person, but there's nobody to check on you in a way. There's no feedback mechanism. The foreign ministry will get angry, but it's almost like a badge of honor if you get yelled at by the foreign ministry. I must be doing a good job if they're yelling.

So I don't think it has much impact. I mean, writing on the police beatings of the Falun Gong practitioners, it might have had some impact on how the police acted later, but I don't think so. I'm not really sure. It's important to write about human rights abuses and stuff like that, don't get me wrong, but I don't think it has a big impact on China. How do I choose articles to write?

I always think that working, especially in a place like China,

Some correspondents would have a really hard time coming to China because they would be used to being able to wake up in the morning and say, "I'm going to write an article on bridges collapsing in my city," and go and start reporting them. And maybe in the afternoon they can write the article or something like that. They talk to a bunch of experts and go interview the mayor and stuff like that. Maybe take two days, but at the end of the day they can, you know, or at the end of the week they could finish their article and write it and it would be over just like that. Great.

But in China and in a lot of foreign corresponding really it's like this, but I think in China it's especially true. It's more like making food like making stew or soup on the burner and you have to opportunistically find stuff like you might need an onion, but you don't have it. You can't go to the supermarket and buy the onion. You have to like you're going out. I found an onion. I go home cut it up and throw it into the pot and then I can add something else and add something else and then when it's ready I serve it and

It sounds like a terrible way to cook, actually. But I think a lot of articles are like this. I'm trying to have these big themes. Like, I want to write about

farmer tax being taxed overtaxed like that was a big theme that I wrote about when I was with the Baltimore Sun and Wall Street Journal and I knew there was this issue I would talk to academics about it I would read scholarly papers on it I would talk to Chinese experts on it and then you the hardest thing was always finding the case study that would that would show that and

So the interviewee is someone who's willing to talk? Someone who's willing to talk and being able to go to that place and stuff like that. And then you find out, okay, well, it's really a problem in this one place in Shanxi and there was this lawyer and maybe you can go talk to them. And then you go out there and make your trip to try to get the color, if you will, but also the anecdote, the case study that you need to make it work. So it's kind of a different way because in Shanghai,

In an open society, you can much more easily then talk to these people and you can set out and say, okay, I'm going to go find these bridges or whatever it is I'm going to

find these farmers, I can go to talk to them. There's a farmers association that will talk to me. If you're an American and you want to, it would be super easy. You could go to the town and talk to people and they would probably talk to you and then you could talk to the mayor or something like that. It would be so much easier. In China, getting to that place, not getting busted by the local public security bureau, figuring it out logistically, that was always the hardest part.

So I'd have a whole bunch of topics I was interested in and working on. I'd have file folders where I would collect information. And then I would sort of have priority lists of things, maybe 10, 20 topics that I was working on. Some of them I never did, but others then, you know, come together. Were there things that you wish you had reported on that you never got around to?

Well, I'm sure. Thinking back to the 1990s, I'm not exactly sure. I always think back to Liu Xiaobo. I just read Perry Link's biography of Liu Xiaobo. I just wrote a review of it for the New York Review of Books. It hasn't appeared yet. Probably it'll appear by the time this interview is finished. It was made public in 10 years.

Anyways, I thought it was a really great book, and I regret that I didn't have a chance to meet him and talk to him. Did you have the chance to? I probably could have if I had made an effort to talk to him. But I got there in 1994, and I also just wasn't interested. Before me, I was this post-Tiananmen correspondent generation. There were people before me who had seen Tiananmen.

like the Nick Kristoffs and people like that, they had reported on Tiananmen. I hadn't and I was kind of not really interested in continually writing about, "Oh, it's the fourth anniversary of Tiananmen, some people got detained. Oh, it's the fifth anniversary, somebody got, oh, it's the sixth anniversary, somebody got detained," and all this kind of stuff. It just seemed to me like this was this

never-ending cycle and it was also frankly I think it's also the easiest kind of journalism to do in China or used to be because Human Rights Watch or Human Rights in China would send you back then a fax with some

information on somebody who was detained, you could go interview them. It would be one of these few articles that you could do in one day. And you could then call back to somebody in the United States to get some quotes or call somebody in Hong Kong in the same time zone to get some quotes and write up the article. And you'd have a feeling of success, a cheongjo-gan.

I've written the article and of course you get a lot of applause for doing that, for writing about those things. And you know, it's good to get that on the record, don't get me wrong, but it's kind of the easiest stuff to do because there's no, those people, and those people want to talk to you, right? Usually the dissidents do want to talk to you.

So as long as you can get them on the phone or go visit them if they're not at your house or us, we'll happily meet you. It's the opposite of government stuff. Government officials never want to talk to you.

That's actually what would be the hardest part. If you're thinking of this puzzle that you're trying to do or this stew that you're trying to do, it would be to get the government's point of view, ironically enough. I mean, you could recreate it by looking at what has been said in the official media, or you could talk to a think tank that's affiliated with the ministry in question and get basically an idea of government policy. But to actually be able to sit down with a government official and ask them about rural taxation or something like that, it was almost impossible.

I get the sense nor did you really want to talk to the government. Your work is less on the Chinese government and sort of getting exclusive access to this person and that person and seems to be more focused on the Chinese society.

Yeah, but I mean if you're doing something on say rural taxation like why farmers, this is a big issue in the 1990s that farmers were being over taxed, they were being taxed like crazy for all these different things. There were riots and protests and stuff. You want to somehow get the government view of it. You kind of need that to be fair. They just didn't want to talk. They just never wanted to talk. I mean I remember once in 2010 I did a series of articles for the New York Times on urbanization

And they had this policy in southern Shanxi province to bring people off these mountains where actually historically people had not really lived. They'd only lived there when the population boomed in the 19th century. And it was very sheer and not very good. It was all terraced. And there were mudslides that had killed hundreds of people one year. And so the government said, "Okay, right. We're getting all those people off there."

So I applied, I heard there was some office in charge of the relocation and

The guy gave me an interview in Xi'an and it was amazing. You went into the room and it was like a war room. You had big maps of the area on the wall with lights and stuff like that. You felt like you were in the NORAD command post. This guy was like, he had all the facts at his fingertips, where they were going to do, what kind of jobs they'd have for them. Of course, the big issue with this is what do farmers do when they can't farm their little fields on the side of the mountain. How much is being invested in? What roads are being built in?

these enormous walls, map. It was this incredible command post they'd set up, you know. And in some ways, it was great PR for the Chinese government because, you know, in some ways, the officials in China, the civil servants, are quite competent compared to many other countries. Like, they have, even like some, you know, party hack,

Shi Zhang or Sheng Zhang, he knows all this shit, right? You can ask him about, what's the agricultural... He's talking endlessly about facts and figures and stuff like that. And they know they're brief in a way that most U.S. officials don't. Most U.S. officials are...

I'm not necessarily that familiar with stuff. The civil servants in China are kind of, that's how they can build like the high-speed rail, they can do all this kind of infrastructure thing because they have good people working for them. But you never get to see that. Like, you know, like the whole building the high-speed rail network. If they had any brains about their PR, they would allow you into like the headquarters of the railway ministry to see their maps and plans and it would be like a great visual thing for television or something.

but they're just too paranoid. Did you have any preconceptions before you went to China? Something that perhaps you changed your mind about later?

I guess I changed my mind over time about the importance of public intellectuals in China. Like, I think initially in the 90s when I was there, I was like, I don't want to talk to these guys. It's like a waste of time. And one of the best, you know, interviews that I did, though, in hindsight was with Wang Xiaobo, the writer, novelist. And I had like one of the last interviews with him, a long interview. And I went with a

Professional photographer Mark Leong and Mark did portraits of Wang. There are no really good portraits except for him, of these by Mark that he did because about this back, you know, people didn't have phones and stuff like that. They didn't take a lot of pictures. So I really should have done more of that. But it was only when I went back to China after the Olympics,

I was then writing a lot for the New York Review of Books and Bob Silvers was like, "Try to let us know what's going on with intellectuals in China." I should talk to them. So I ended up doing a Q&A series with them, which is still on the Review's website. I think that probably... and this is what led to the book Sparks, ultimately, because I think I began to realize that this was important.

That's all for today, thank you for listening and if you enjoyed this one you may consider subscribing to our sub stack under the same name Peking Hotel with links in description and I'll talk to you next time.