Chapters

Shownotes Transcript

Hi, it's Phoebe. We're heading back out on tour this fall, bringing our 10th anniversary show to even more cities. Austin, Tucson, Boulder, Portland, Oregon, Detroit, Madison, Northampton, and Atlanta, we're coming your way. Come and hear seven brand new stories told live on stage by me and Criminal co-creator Lauren Spohr. We think it's the best live show we've ever done. Tickets are on sale now at thisiscriminal.com slash live. See you very soon.

Hey, I'm Sean Ely. For more than 70 years, people from all political backgrounds have been using the word Orwellian to mean whatever they want it to mean.

But what did George Orwell actually stand for? Orwell was not just an advocate for free speech, even though he was that. But he was an advocate for truth in speech. He's someone who argues that you should be able to say that two plus two equals four. We'll meet the real George Orwell, a man who was prescient and flawed, this week on The Gray Area. Let's just start with you both introducing yourselves. I'm Lynn Matthews.

And I'm Alan Matthews. And tell me a little bit, I mean, both of you worked with heroin users for a long time. Have any of you ever tried heroin? Of course we have, yeah. We were hippies. We met Lynn and Alan Matthews in Liverpool, a city built around a major port in the UK. It was once extremely wealthy.

In the 1800s, there was so much trade in Liverpool that a banker's magazine wrote, "New York is the Liverpool of America, as Liverpool is the New York of Europe." How does the rest of England view Liverpool? I think they view us as being very different because we don't view ourselves as being English. We think we're superior. And we are. By the 1950s, trade in Liverpool had started to decline.

Later, many dock workers lost their jobs and a left-wing group took control of the city council. Their slogan was, "Better to break the law than break the poor." I was a hippie, like, from the late 60s. So obviously I smoked pot because that was mandatory. And then I took acid. Pot smokers always had a few heroin users within their circle and we'd look after them, you know.

So they said to make sure they didn't come to any harm and that, you know. But then back in those days cannabis was seen as worse than heroin really, in a way. Like Glenn, I was a kid of the 60s, 1967, Sgt Pepper's, The Beatles, Yellow Submarine. I was 13 years old and I thought drugs seem, this looks great, that's the life for me. And I actively went out and found where I could get some drugs from. At first it was amphetamine tablets, then it was pot and I grew the hair.

and I wore the flares, and I went to the pop festivals and did all that kind of stuff, and took all the drugs that came my way. The most famous thing about Liverpool is the Beatles. We saw a bronze statue of the four band members near the water. Dozens of people were waiting to take a photo with it. There are two Beatles museums, and there are Beatles tribute bands that play every weekend.

In the 1960s, the Beatles had talked about their drug use in a few TV interviews, mostly marijuana and LSD. John Lennon called their album Revolver, the pot album, and the group took out a full-page ad in a London newspaper to argue for legalizing weed. Later, the BBC censored three songs on their album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band because of perceived references to LSD and heroin.

One of them, the song A Day in the Life, the BBC banned because of the lyrics in the final verse. I read the news today Over a thousand holes In Blackburn, Lancashire The BBC thought the lyrics were about track marks, open wounds in people's arms from injecting drugs, often heroin. John Lennon said they were actually about potholes in the road. I'd love to turn...

The BBC director of sound broadcasting still wrote a letter to the band, saying, quote, We have listened to it over and over again with great care, and we cannot avoid coming to the conclusion that the words, I'd love to turn you on, followed by that mounting montage of sound, could have a rather sinister meaning. Turned on is a phrase which can be used in many different circumstances, but it is currently much in vogue in the jargon of the drug addicts.

In 1967, a reporter asked Paul McCartney why he'd been so open about using LSD. Well, do you think you have now encouraged your fans to take drugs? I don't think it'll make any difference. You know, I don't think my fans are going to take drugs just because I did. The thing is, that's not the point anyway. You know, I was asked whether I had or not. And then from then on,

The whole bit about how far it's going to go and how many people it's going to encourage is up to the newspapers and up to you, you know, on television. I mean, you're spreading this now at this moment. This is going into all the homes, you know, in Britain. And I'd rather it didn't, you know. But you're asking me the question. You want me to be honest. I'll be honest, you know. But as a public figure, surely you've got a responsibility to lots and lots of teenagers. No, it's you've got the responsibility. You've got the responsibility not to spread this now.

You know, I'm quite prepared to keep it as a very personal thing, if you will too. By the 1980s, Liverpool had what journalists called a heroin epidemic. People started calling it Smack City. A new kind of heroin had become available from Southwest Asia. It was a lot cheaper, and you didn't have to use a needle to inject it. You could smoke it. Brown smokeable heroin arrived here around 1980, 1981.

It just seemed every other kid I was talking to was on the foil, smoking heroin off tinfoil. I thought, wow, this is huge. In the 1987 book, The New Heroin Users, Jeffrey Pearson quotes one young person saying, the next minute it was everywhere, like it just sort of took Liverpool by storm. There was a popular myth that smokable heroin, unlike injectable heroin, wasn't addictive. Within a few years, tens of thousands of new people were using it.

Most of them were young, working class and unemployed. Lynn Matthews was 25 when she first tried heroin. Alan was around the same age. For me, using heroin recreationally was not a big deal. I wasn't particularly enamored of it. I was more into psychedelics. I was more into LSD. That was more of an interesting thing. Heroin, you take heroin, you sit down, your eyelids become heavy, you sit back and you just drift away for a couple of hours.

In the summer of 1985, a 14-year-old boy in Liverpool named Jason Fitzsimmons died of a heroin overdose. There weren't many places that young people addicted to heroin could turn for medical help. Some had been going to the Merseyside Drugs Council, a volunteer organization in Liverpool for counseling and advice. A spokesperson for the council had told the local paper they were seeing young teenagers come in. The chairman of the organization said,

It is only the tip of a massive iceberg. We are on the brink of a complete catastrophe if something is not done immediately to stop the drug coming into Liverpool and to help the kids who are hooked. I'm Phoebe Judge. This is Criminal. Before 1868, drugs were virtually unregulated in the UK. Back then, opium was sold over the counter in grocery stores and pharmacies. Queen Victoria used it.

She also used cannabis and cocaine. Opium pills for the rich were coated in gold and silver. One druggist marketed a mixture of alcohol and morphine as cough medicine. It was called Ayers Cherry Pictoral, and its ads featured pictures of doves and smiling children. But by the 1870s, medical journals started to publish articles about morphine addiction. They realized it was a problem.

A chemist at the German pharmaceutical company Bayer was working on new drugs. He synthesized aspirin, and less than two weeks later, he synthesized heroin. Bayer started marketing heroin as a safe, non-addictive alternative to morphine. One charity in the U.S. started a campaign mailing free samples of heroin to any morphine addict that wanted one. Other doctors claimed that morphine addiction could be cured with cocaine.

Then, after World War I, the UK passed its first so-called Dangerous Drugs Act. It became a criminal offense to possess drugs like cocaine, opium, and heroin, unless they were prescribed by a doctor. They needed to decide how to treat people who were already addicted.

They set up what has become known as the British system. And they said, yes, you can maintain people who have existing addictions on medical opioids or on cocaine or whatever they are addicted to, because this will keep them in society, will help them function and is basically a better way of dealing with it than condemning them to live in the criminal underworld.

Maya Salovitz is a journalist in the U.S. She writes about drugs and policy. Everybody sort of tends to assume that at some point, like, this very serious scientific committee sat down and said, OK, let's decide which should be legal and which should be illegal based on the risks. She says that's not the case. Which drugs were criminalized had a lot to do with who was using them. In the years before Liverpool's heroin epidemic, there were only a few people using heroin—

They were usually middle class, and it was given to them by doctors. If you got addicted to, like, opiates in the UK, you might be trying to scam a doctor to get some drugs, and the doctor will be like, "You know what? You're scamming me to get drugs. I'm just going to give you the drugs. You don't have to scam me. Like, you don't have to pretend to have pain." Opium was getting big in the US around the same time as it was in the UK. During the Civil War, the army distributed millions of opium pills to soldiers,

Doctors would prescribe morphine to women for things like period cramps and morning sickness. But later, people started to view opium use differently. Opium smoking dens opened by Chinese immigrants were becoming popular. And in 1914, Congress effectively banned opiates and cocaine. And people who were already addicted couldn't turn to doctors for prescriptions like they could in the U.K.,

Our Supreme Court ruled that, no, this can never be part of legitimate medicine. It's not a medical practice. It's not okay. In the U.S., the, quote, police era of narcotic control began. Prohibition officers threatened and prosecuted physicians for prescribing to people who were addicted. But in the U.K., as one journalist wrote, addiction was considered a problem for physicians rather than law enforcement.

For a while, opiate use in the UK declined. The UK had virtually no cocaine use and virtually no heroin use. The people who were using those drugs were basically pharmacy robbers. And when they got caught or when a doctor figured out, hey, this person is addicted and scamming me for drugs and just gave them the drugs, this problem was resolved. And what it meant was that there weren't a lot of

people selling heroin on the street because there wasn't much of a market for it. And the people who were already addicted had no incentive to try to sell to other people because they had all they wanted anyway. And so it kind of kept the problem really contained for many years. But when the 60s and 70s hit,

The entire Western world was filled with a wave of youth drug use. So when the 60s hit the British system, some of the doctors basically began profiteering off of selling drugs. There was a whole panic over the prevalence of drug use. And so a lot of the system was really shrunk back.

In the 60s, one of the doctors licensed to prescribe heroin was named Lady Isabella Frankow. She was known for her, quote, lunatic generosity, sometimes prescribing more than 400 heroin tablets a day to a single patient. When she died, a doctor named John Petro took over most of her patients. He would write prescriptions in cafes, on napkins and cigarette packs.

In 1968, John Petro talked about what he was doing in a television interview. Fifteen minutes after the interview, Scotland Yard showed up to arrest him. That same year, the government passed new restrictions on which doctors could prescribe for addiction. Doctors started prescribing less heroin and more methadone, a drug that people could take instead of heroin to help with withdrawal. Alan Matthews says that by the 70s,

Many of the people he knew using heroin still got it from the doctor. You could go to the doctor, say, Doctor, I'm an addict, and they'd get on a prescription. And that's how it was controlled. But it was becoming much more unusual for doctors to prescribe heroin. Most heroin was coming from the black market. And in 1983, Alan Matthews ran into someone he knew in high school. His name was Alan, too. Alan Perry.

And he said to me, "Hey, you know about drugs, don't you?" And I said, "Yeah, because I used to score acid off them in the 70s in school." He said, "Come and work for us." I said, "What?" He said, "We're setting up a drug training and information center." I said, "Oh, right, okay." He said, "Because of this big outbreak of heroin in Liverpool." We need somebody to go out there and interview these young heroin addicts, find out what they know, how they got into it, how it's affected their lives, how it's affected their families, how it's affected their communities.

and see how best we can control the situation that was getting out of hand. They started working together. At first, Alan Matthews' job was just talking to people who used drugs. So I'd sit down with a young heroin addict with an old C90 tape recorder. So the interview lasted an hour and a half. Click, right, tell me about your life. Lots of them were out of work. Unemployment in the UK was as high as it's ever been in 1984—

Over three million people were without jobs. These were young people who'd gone through their education in the clear understanding that when they finished school, there was nothing for them. There was no jobs. Heroin came along and gave them a full-time job. Taking heroin is a full-time job, seven days a week. You have to get up in the morning, finish off the little bit of heroin you had from last night. That would get you well enough to get out on the street to go on what they call grafting trips.

which means stealing, shoplifting, to earn enough money to get £10 worth of heroin. You go to the dealers, get the £10 worth of heroin, smoke half of that, then go home, finish it off, and get up the next day and do exactly the same thing. So it gave them a routine, a framework to their lives. Like, one young woman I interviewed, I said, so, why do you take heroin? And she said, it gives me relief from who I am. I thought, wow, that's...

Heavy, man. That's deep. That's insightful. She discovered something that when she took it, got all those horrible, dark, painful, sharp, jagged emotions and memories, wrapped them up in cotton wool and put them in the attic for four hours. And she got relief from stuff she couldn't get away from.

We have this idea that, you know, you get exposed to a drug and it's the best thing ever and you give up your happy life for the drug. That is very, very rare. What typically happens when someone becomes addicted is that they're searching for something, for some way to feel better, to feel comfortable in their skin, to connect with other people, and they find that a substance eases this for them. Addiction kicks people who are already down. It is not equal opportunity.

It wasn't just Liverpool. In Edinburgh, in Scotland, one doctor said, Police in Edinburgh started raiding people's homes and confiscating needles.

They cut back the supply of syringes. And so what they basically did was make it as bad as it could be, because the crackdown basically led to more people sharing the same needles. One person said they would sharpen blunt needles on matchboxes to use again. In Liverpool, the government health authority was worried. They knew who Alan Perry was, and they went to him for help.

He was one of the first people that the public health folks turned to in order to reach out to the injecting drug use communities because, like, he had long roots there. The health authority convinced Alan Perry that they should be involved in the Drug Training and Information Center, and they started funding it. We became aware of this weird virus in the USA that was killing gay men in San Francisco and drug injectors in New York City.

Alan Parry went over to New York, and John Ashton from these big knobs at the Health Authority, to talk to treatment services there and find out what this HIV thing was, because we'd never heard of it. They were so concerned by what they found there that they came back to Liverpool and they said, look, this virus is spread by people sharing injection equipment. The doctor in Edinburgh who'd seen patients dying of overdoses, Roy Robertson, got a hold of an HIV test.

He started testing the blood of people who were injecting drugs and found that 60% were HIV positive. People started calling Edinburgh the AIDS capital of Europe. In Liverpool, Alan Matthews remembers hearing the news. And we thought, shit, hang on, this is no longer 3,000 miles across the Atlantic. This is 300 miles with the M6 motorway. We've got it. It's here. We'll be right back.

Support for Criminal comes from Ritual. I love a morning ritual. We've spent a lot of time at Criminal talking about how everyone starts their days. The Sunday routine column in the New York Times is one of my favorite things on earth. If you're looking to add a multivitamin to your own routine, Ritual's Essential for Women multivitamin won't upset your stomach, so you can take it with or without food. And it doesn't smell or taste like a vitamin. It smells like mint.

I've been taking it every day, and it's a lot more pleasant than other vitamins I've tried over the years. Plus, you get nine key nutrients to support your brain, bones, and red blood cells. It's made with high-quality, traceable ingredients. Ritual's Essential for Women 18 Plus is a multivitamin you can actually trust. Get 25% off your first month at ritual.com slash criminal.

Start Ritual or add Essential for Women 18 Plus to your subscription today. That's ritual.com slash criminal for 25% off. Tell me where we are right now. This is the Philharmonic Pub, which is probably one of the oldest pubs in Liverpool.

As you can see, it's all still as it was. So it's been around for a long... And who would come here? Who comes here? Everybody. Anyone who comes to Liverpool will eventually end up here at some time. And you used to spend time here? Yes. Used to go out round here, you know, when I was younger. Back in the 80s, it was where Alan Matthews and Alan Perry and their colleagues from the Drug Training and Information Centre would sometimes go after work.

A lot of the strategy was developed in one of the Brahms and Liszt rooms. Do you know Brahms and Liszt? The composers? Yeah. Do you know what Brahms and Liszt means in Cockney rhyming slang? I don't know. Pissed. I'm a bit Brahms and Liszt. They'd heard of a group of drug users in the Netherlands who called themselves the Junkie Bond. Without support from the government, they'd started an underground needle exchange. You bring drugs.

Dirty needles in, we'll give you clean ones. They would give out syringes in the street and provide them in bulk to drug dealers. It reduced the chances of somebody sharing a syringe. Just common sense, pragmatism. We thought, well, we could do this here. We asked Alan and Lynn Matthews to take us to the building where it all began. It was around the corner from the pub in a plain brick building. It's just on Maryland Street here, number 10 Maryland Street. And here's a guy going in now.

Hiya. Hello. Do you live here, work here? What is it? These people are from the USA. We're doing a podcast about what we did in this office 40 years ago. We started the first needle exchange in here to combat AIDS, which was very successful. Could we just have a quick look inside the door? Did you know that that was going on here? No, no, I didn't. This was where the first needle...

It was given out in Liverpool. I didn't have a clue that was there. It's like half student and half just like flat. Yeah. See, you could come in through the door here. Reception was on that side there. There was a corridor here and the toilet was just there. So we thought that's the easiest access point.

So, you know, people were coming off the streets, didn't even have to go into reception, just go in. Somebody would be around, yeah, what have you got? Okay, dump all those used syringes in a sharps bin. What do you need? Two mils, one mils, you know, swabs, condoms, advice leaflets about AIDS, that kind of thing. So they'd show up here, they'd come in, you wouldn't ask any questions, you would just say, what do you need? Yeah, yeah.

The only information we required was some kind of identifier. So it could be your initials, it could be a made-up name. One guy was Dan Dare, another guy was Batman. One guy, I said, just give us your initials. He said, OK, D-N-I. And I thought, Grace, OK, D-N-I.

Alan Matthews remembers they were worried about what newspapers would say about what they were doing. Local papers called the Liverpool Echo. And at that time, they were running a really sensationalist campaign about a generation in peril. Heroin, doom, death, destruction, families destroyed. Really emotional stories about what this thing, heroin, was doing to people.

So the needle exchange approached the Liverpool Echo and asked them not to write anything for six weeks. They wanted a chance to prove themselves. The program wasn't announced publicly. No posters or PSAs. Only word of mouth. How long did it take for the first person to show up here? Within a couple of days, because we knew them. I knew the people on the scene. And one guy that came in regularly was a guy called Tommy. And he used to come in with, like, a few syringes. Nope.

In conversation with him, I knew he was running a shooting gallery in his flat. He was a heroin dealer. People would come in, five quid's worth of heroin, and then shoot it up and then leave. And I was like, what happens with all the syringes? He said, well, they're in a big bin bag, keep them by the side. So somebody would come in, get five pounds worth of heroin, rummage through the bag of used syringes to find a relatively clean-looking one. And I was like, oh, Tommy...

You've got to stop that. He said, well, how can I do that? I said, bring all your dirty syringes in and we'll replace them. Okay, he came back the next day with three bin bags full of syringes. Right here? Yeah. He was like, whoa. And there was pins sticking out and there was blood dripping from them. He's like, oh my God, Tommy. So we gave him big sharp bins, boxes of syringes, swabs, needles, all that kind of stuff. So we ran a satellite needle exchange from a dealer's house.

Because we knew, you know, if anybody's going to see a drug injector, it's the drug dealer. And that became very successful, and then Tommy got busted, and that was the end of that. So, but it was really successful for a while. Word slowly spread, but not everyone felt safe to visit, including some sex workers. So we'd, you know, we'd say, why don't more of the girls come down and get some clean needles? They're like, oh, no, they're not going to do that. Well, why? Well...

First of all, they've got to walk past the police station. And you're part of the health authority, which sounds scary. A lot of these girls have kids, so they're not going to walk in and say, hi, I'm injecting heroin and I'm selling sex and I've got three kids. Social services will be all over them, take the kids off them. They were like, no, that's a misconception. That wouldn't happen. It's all confidential. And they were like, well, no, they don't believe you. So we sat down in the pub...

One Friday evening, thought, okay. So we need some outreach work. Okay. Who's going to do that? Said five men sitting around the table. Well, obviously it's not going to be a man. So we need a woman. It's dead chatty, approachable, engaging, humorous. But she's got to have, you know, no fear. And have balls of steel.

And I said, that's my wife. And that's where you came in. Yeah, yeah. No, because I started out as a hairdresser and...

Obviously hairdressing is a good grounding for counselling as well because everyone tells their hairdresser their problems. And I also worked with a lot of sex workers who used to come in to get their hair done. But obviously hairdressers pay isn't very good and I was fortunate that I could sing. So in 1975, before we'd even met, I used to be a lead singer in bands so I got into bands and then I got into acting and things like that so I was

sort of hairdressing by day and treading the boards at night. So that gave me a good... Because, you know, playing all the clubs around Liverpool and things like that, you've got to be... And being the only girl in a band is quite, you know... So that gave me the groundwork to do the job.

On Lynn's first day, she was just supposed to go out and talk with people. Somebody was going to go out with me, but I'm one of these, I'm a bit impatient. So I thought, well, I'll just drive around and see who I find. And I just saw one woman who was obviously working.

and just went up to her and said, "Hiya, my name's Lynne. I'm from the health authority. They want to know what you need, what's going on." And she was like that. I said, "You know, I've got condoms here if you need them." And we just got chatting and she took the condoms. And then before I knew it, I was surrounded by a group of women who were wanting to know who I was.

And one of the first questions they asked me was, are you a social worker? And I went, no, I haven't even got a no level. Which, that's the qualifications you have when you leave school. So that immediately put them at their ease, you know. Lynn says as she was talking with the women, police officers approached them. They hadn't seen her around before that night.

They wanted to know who she was and what she was doing distributing condoms. So then they said, well, have you got any for us? And I went, no, I'm sorry, I don't carry small, which that made the girls howl. So they thought the fact that I kind of did that with the police, that kind of set the tone. You can tell when people's genuine or whether they're not genuine, you know.

And with me, what you see is what you get. You know, I'm like Marmise. People either really like me or really hate me, you know. So the problem was that they'd have to walk past a police station to get here. Police station's not there now because obviously everything's been developed from how it used to be. We walked past where the police station had been. So basically this was where the beat really started, you know.

the girls would start working, you know, you'd start seeing the odd one or two scattered around. It had been known as the Red Light District since the '50s. I think it was moved up from the city centre, wasn't it? From Lime Street. There was always like a myth that Lime Street was where sex workers worked. You know, because there's a song Maggie made, "She'll never walk down Lime Street anymore." Lynne says that one of the women she met started driving around with her at night.

She would help introduce Lynn to other women they saw working. I'd get out the car and she'd say, "This is Lynn. She's sound. You can talk to her." And then we'd have a little chat, give them condoms. And then we'd go back around again. So I got to know everyone. So there was a real strong... And we all got very, very close, you know? So it was quite humbling, really, in a way, that they actually did give me that trust.

On her nights at work, Lynn went from carrying condoms to carrying needles. I used to go into crack houses where people were hitting up so I could observe what they were doing and then go, oh, hang on, you're not going to share that needle, are you? No, no, no. And that was how we came to start carrying needles as well. And we kept it all very, very low-key because we thought we don't want the press all over it. We'll see how it works. Did people come there and just say, you must be a cop?

You must be the police. I don't understand. We didn't look like police. Yeah. Police have a certain look about them. There was always one way in Liverpool that you could always tell if someone was an undercover copper. Because you'd look at their feet, because they always used to use the same shoes and they always seemed to have flat feet. And that's being judgmental. Yeah, that is being judgmental. But I think it's the way, you know, the way you are and the way you act...

Lynn and Alan and their colleagues talked to the police and asked the drug squad to give them some space. It was a sort of handshake agreement. The head of the drug squad was a guy called Peter Deary. And he was a very pragmatic, very practical guy. And we said, look, this is happening. We want to do this to stop HIV. And he was like, fine. Because we said, all you've got to do is park a police car across the road and nobody will come in. He said, no. He said, I'll tell the patrols to avoid the area.

In fact, we'll go a little bit further. We'll install sharps boxes in every police car. So if they pick somebody up with used sharps, they can dispose of them safely in the sharps box. And we'll bring them around to you for fresh ones. So the police used to drop people off to get clean syringes, which was fantastic. The Liverpool Echo had agreed to wait and watch before reporting on the needle exchange.

And on December 4th, 1986, they published a story with the headline, Syringes Swap Shop for Addicts, City Secret Battle to Beat AIDS. The reporter wrote, The unit says it is the first scheme of its kind in Britain. The article quotes Alan Perry, We have been operating the scheme secretly because we wanted to prove it could be successful before we were snowed under with criticism.

In six weeks, we saw over 300 people. We'll be right back. In the late 1980s, journalists were coming from all over the world to see what Liverpool was doing with the needle exchange. People were calling it harm reduction. Alan and Lynn Matthews say that while they were getting a lot of positive attention from around the world, plenty of people in Liverpool didn't like it.

Especially parents. Parents support groups were like, these nutters are giving out needles to junkies, they're getting our kids on heroin, we're all going to get AIDS. And, you know, I don't blame them, it's a very emotional issue. In 1990, the Liverpool City Council, the one with the slogan, better to break the law than break the poor, declared the needle exchange was a, quote, experiment doomed to failure.

And Liverpool City Council at the time was a very hard-left socialist council run by a group called Militants, who were very, you know, come the revolution comrades, all that kind of stuff. They took on board exactly what parents and community groups were telling them. This is devastating the community. You know, if you've got a family and your 18-year-old son steals your mother's wedding ring to go and buy heroin, you know, can you imagine the rift that's going to cause? And that was going on all over the place, you know.

So they started championing the cause of the poor parents and the communities and what heroin was doing and, you know, come the revolution, we'll have no heroin and, you know, all that kind of stuff.

Journalist Maya Salovitz says the city council opposed the needle exchange. They basically thought that we should not be giving out clean needles or prescribing heroin because, you know, they were worried about the opiate of the masses. They were worried that drugging the masses would prevent the revolution.

Liverpool City Council wanted to shut the needle exchange down and suggested holding dry and alcohol-free parties to entertain young people as an alternative. But there wasn't much they could actually do to stop the exchange. The health authority didn't have to answer to the city council, unlike in the U.S., where states can ban needle exchanges. Needle exchanges in the U.K. only need the support of the central government.

And Margaret Thatcher's government had decided to support the needle exchange, so it stayed open. Was the government maybe more apt to support this because of their, the liberalness of the way that they had supported people dealing with addictions before? I don't think it was so much that as they were really scared and afraid.

One of the people involved in the Liverpool harm reduction group was someone who could get Margaret Thatcher on the phone personally. He was like a conservative guy. And there was a conservative perspective that was basically like AIDS is going to cost a fortune. We don't want our daughters getting it.

let's do this even though it may be distasteful because we want to protect everybody else. And in the United States, we just couldn't do this. We just were like, drugs are bad, drugs are bad. And maybe if people die as an example, then they won't do drugs and the kids will be saved. Maya Salovitz was a young journalist when she visited Liverpool for the first time in the early 90s.

You had experience with drugs before you had gotten to Liverpool? Oh, absolutely, yeah. I mean, I had been addicted to cocaine and heroin, and I was several years into recovery myself. She was familiar with various policy approaches to addiction and remembers thinking that the way the U.S. was responding, criminalizing addiction, couldn't be right. Doctors giving drugs to addicted people didn't seem right either.

She says the more time she spent in Liverpool, she started to change her mind. She began dating someone who worked for the needle exchange. By the early 1990s, the government support for the group in Liverpool started to dry up. One doctor who operated a heroin prescribing clinic, a man named John Marks, was getting a lot of attention. He went on 60 Minutes in 1992, along with Alan Perry.

The interviewer asked John Marks how he would respond to critics who called him a quote "legalized dealer," a pusher. And John Marks said, "I'd agree." One drug policy scholar wrote that this was embarrassing for Margaret Thatcher's government and that members of government began to feel that Liverpool should not continue to be treated as a quote "offshore island" in drug policy matters and needed to be brought back into line.

John Marks' clinic was shut down. He eventually moved to New Zealand. After he left, a lot of doctors would not pick up his patients and some of them died. But the real backlash was...

conservatives began sort of organizing this idea that we need a recovery model. We need abstinence, not harm reduction and all kinds of things. Drug services, treatment, harm reduction, like everything just got cut dramatically. There was just all kinds of austerity. And so like this very conservative

wonderful early movement that had done so much to influence the rest of the world just kind of died in its own backyard. It had lasted around 13 years. In that time, the HIV infection rate among drug users in other places, Edinburgh and New York, had reached 50% or higher. Maya Salovitz says in Liverpool, it never reached 1%.

So there was no HIV epidemic in Liverpool at all? No, there was not. And, you know, it's weird, like, that we just don't think about these things. Like, it's like part of the reason that I believe the backlash against harm reduction succeeded in the UK was that they did not have an HIV epidemic. They didn't realize what they'd prevented.

So it's like sometimes something can be too successful for its own good. I think in Liverpool now we've gone backwards with drug service provision. We were more radical back then than what we are now. In 2021, there were 192 drug-related deaths in the county where Liverpool is. And the rate of drug offences there was higher than anywhere else in England or Wales by a long shot.

The thing about drug use is it's so, especially injecting drug use, it's so heavily stigmatized. And people who are on the street and are injecting are just, you know, people cross the street to avoid dealing with them. They're just seen as garbage. It is just awful. And so when they go to a place that is just for them,

That is like, here, we want you to live. We're not trying to get you to stop doing anything. We're not trying to change you. We're not trying to fix you. And this is why, like, so many people misunderstand harm reduction and they think, oh, it's just about, you know, here, have a needle, go kill yourself. No, it's about we care enough about you exactly as you are to want you to be as safe as you can in the setting that you are in. Maya Salovitz has written...

When your focus is reducing harm rather than measuring the number of arrests or the amount of drugs seized, if your metric is instead, are people staying alive, then your interventions are going to be different. Do you look back on that time now and think, we did a lot of good? Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. We don't know how many lives have been saved, but it must be, you know, you can't quantify that. The knock-on effects of...

doing something, engaging with people where they're at in a non-judgmental way, being pragmatic about stuff. You really can't count the heads on that. You can't count the numbers on that. It's just, it's too big. There's too much. Criminal is created by Lauren Spohr and me. Nadia Wilson is our senior producer. Katie Bishop is our supervising producer. Our producers are Susanna Robertson, Jackie Sajico, Lily Clark, Lena Sillison, Sam Kim, and Megan Kinane.

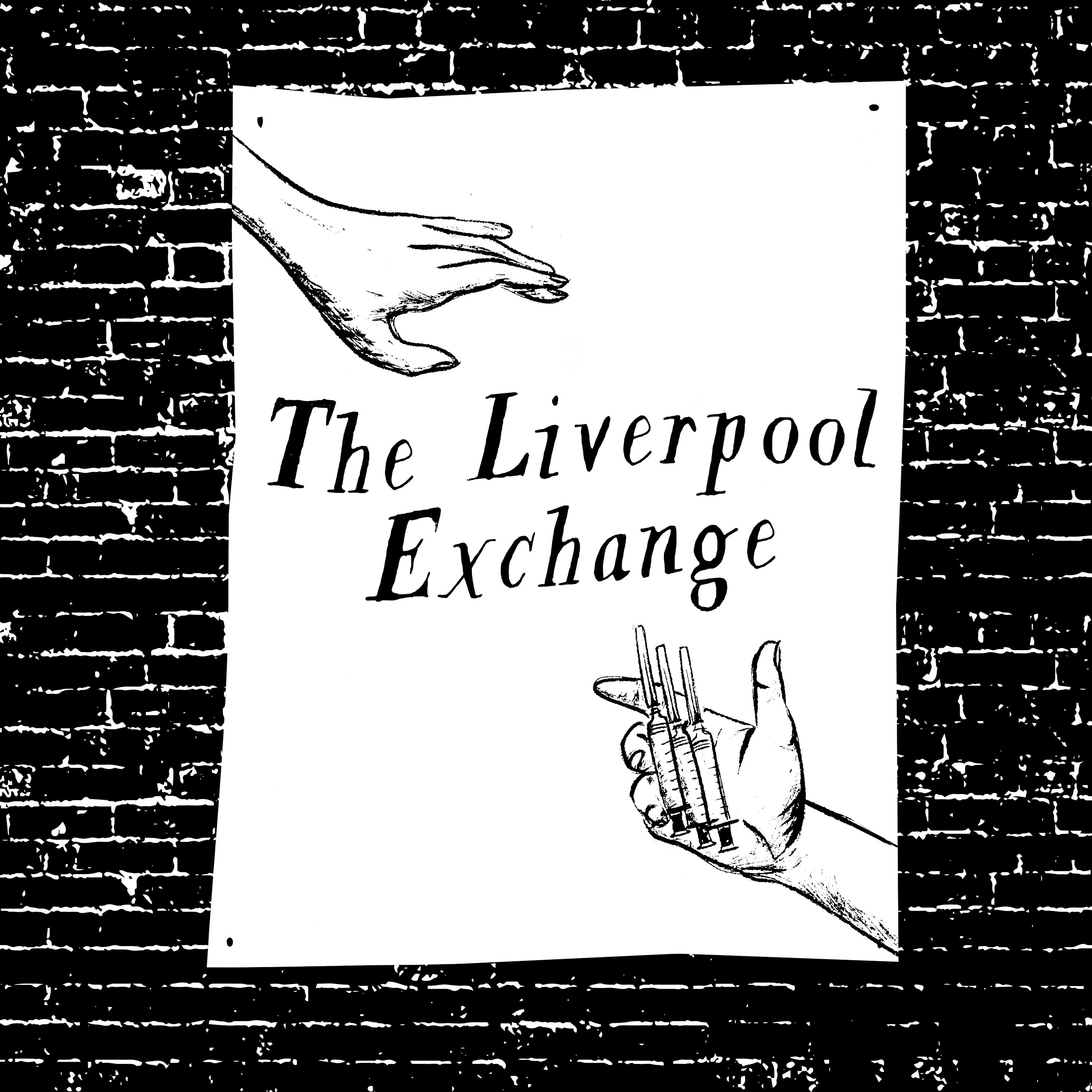

Our technical director is Rob Byers. Engineering by Russ Henry. Special thanks to Michelle Harris. Julian Alexander makes original illustrations for each episode of Criminal. You can see them at thisiscriminal.com. Maya Salovitz's book is Undoing Drugs, How Harm Reduction is Changing the Future of Drugs and Addiction.

You can sign up for our newsletter at thisiscriminal.com slash newsletter. And if you like the show, tell a friend or leave us a review. It means a lot. We hope you'll join our new membership program, Criminal Plus. Once you sign up, you can listen to criminal episodes without any ads and get a bonus episode each month. To learn more, go to thisiscriminal.com slash plus. That's thisiscriminal.com slash plus.

We're on Facebook and Twitter at Criminal Show and Instagram at criminal underscore podcast. We're also on YouTube at youtube.com slash criminal podcast. Criminal is recorded in the studios of North Carolina Public Radio, WUNC. We're part of the Vox Media Podcast Network. Discover more great shows at podcast.voxmedia.com. I'm Phoebe Judge. This is Criminal.