Deep Dive

Why did Sunil Amrith write 'The Burning Earth' from a vantage point outside the global North?

Sunil Amrith wrote 'The Burning Earth' from a vantage point outside the global North to provide a more global and inclusive perspective on environmental history. His background in India and Southeast Asia allowed him to highlight elements of the story that might look different when viewed from Asian and global South perspectives.

How did Sunil Amrith's urban upbringing in Singapore influence his approach to environmental history?

Sunil Amrith's urban upbringing in Singapore, a city that grew rapidly and relied heavily on technology, initially made him skeptical of environmental concerns. His interest in environmental history grew from a starting point of political questions about justice, equality, and rights, and he later integrated these concerns as he realized the inseparability of environmental and social issues.

Why does Sunil Amrith believe that environmental concerns are inseparable from political rights and social justice?

Sunil Amrith believes that environmental concerns are inseparable from political rights and social justice because he observed how environmental risks and disasters are often the result of political and economic decisions. The catastrophic flooding in cities like Yangon, Bangkok, and Mumbai in the early 2010s highlighted the interconnectedness of these issues.

What historical patterns does Sunil Amrith see echoing in the current moment of climate change?

Sunil Amrith sees historical patterns of resource conflict, such as water wars and grain conflicts, echoing in the current moment of climate change. He also notes the persistence of language and imagery that reflect an exclusivist view of resource security, similar to earlier periods.

How does the concept of 'wastelands' relate to the colonization and exploitation of land?

The concept of 'wastelands' is a medieval notion that certain lands are being wasted because they are not being cultivated. This idea has been used to justify the displacement of indigenous peoples and the exploitation of land for agricultural or economic purposes, both in Europe and in colonized regions.

Why is the island of Madeira considered an early example of boom and bust in the context of environmental history?

The island of Madeira is considered an early example of boom and bust in environmental history because it saw rapid deforestation and the establishment of sugar cane plantations, which were tilled by slave labor. This focus on maximizing quick profits for distant investors led to the exhaustion of the land and a constant moving of the frontier to new areas.

Why does Sunil Amrith suggest that emissions are the ultimate act of colonization?

Sunil Amrith suggests that emissions are the ultimate act of colonization because they disproportionately affect those who have contributed the least to those emissions. The cumulative effects of emissions colonize the future, impacting the most vulnerable populations and regions.

How does the concept of 'forgetting' play a role in the environmental challenges we face today?

The concept of 'forgetting' plays a role in environmental challenges because it allows us to ignore the consequences of our actions and the interdependence with nature. Technologies like air conditioning and fossil fuels enable us to forget the natural systems we depend on, leading to a disconnection from the environment and a failure to address long-term sustainability.

What historical document does Sunil Amrith compare modern climate agreements to, and why?

Sunil Amrith compares modern climate agreements like the Rio Earth Summit, Kyoto Protocol, and Paris Agreement to the Charter of the Forest. While the Charter of the Forest was a legally enforceable document that recognized people's dependence on nature, modern climate agreements often lack enforceability, which is a significant challenge in addressing climate change.

What does Sunil Amrith see as a cause for optimism in the face of climate change?

Sunil Amrith sees the environmental movement as a cause for optimism, despite setbacks. He believes that the movement mobilizes more affiliation and energy than any other movement globally. He also sees progress in terms of mobilization, consciousness, and political action, though these are generational processes and will take time.

Shownotes Transcript

Five. Time. Fifteen.

Hi, good evening and a big welcome here to 5x15 tonight. And I couldn't be more thrilled to be introducing our two speakers. We're here tonight primarily to talk about this astonishing new book called The Burning Earth, written by Sunil Amrith. And it is an incredible story of the environmental history of the world and the earth and the planet that we live on. And any idea that you might have had that what we're going through now was the first time that

man has really trashed the planet well forget it because what you're going to learn in the next

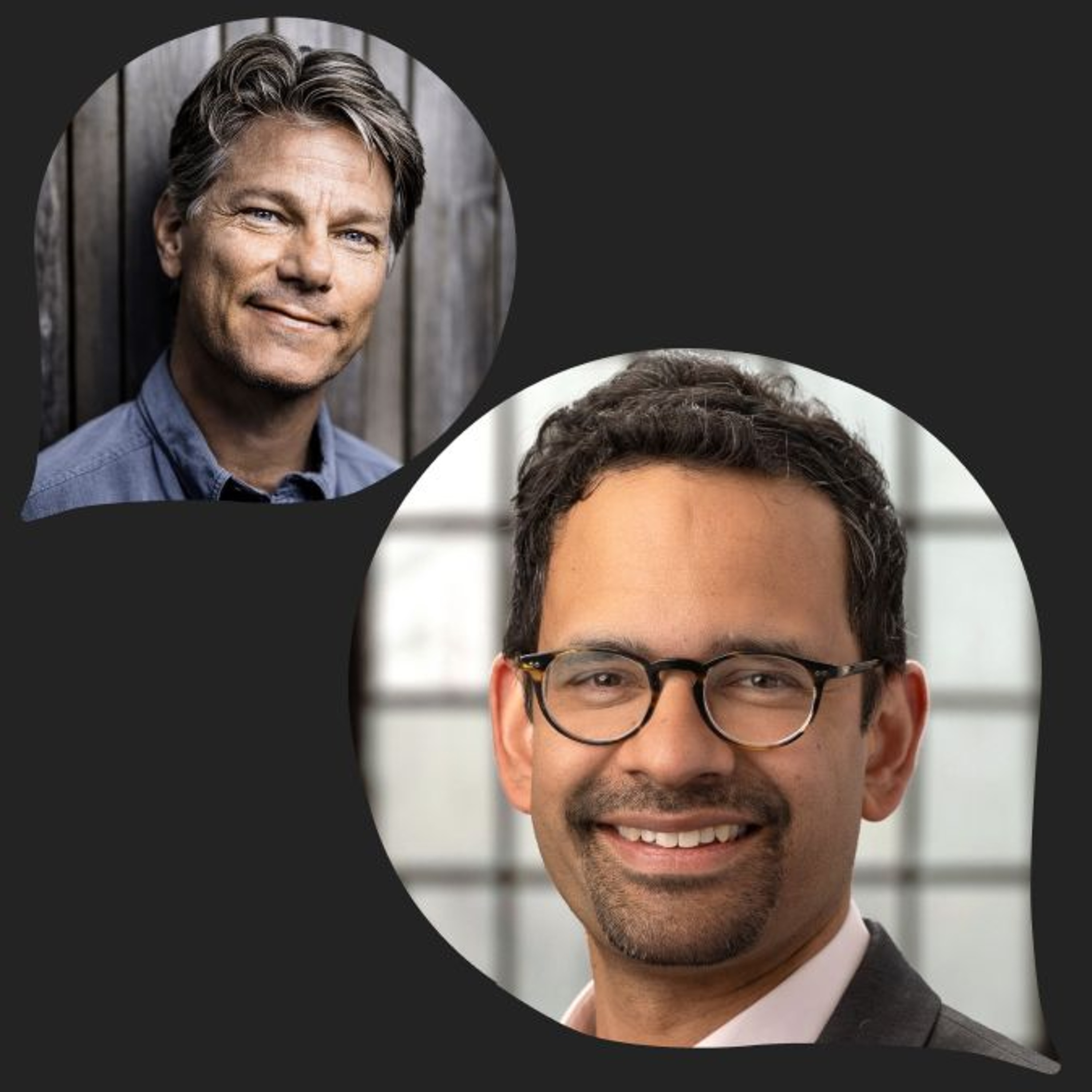

is that things have been not so great for a very long time. And I'm really thrilled that Sunil's going to be in conversation with John Valant, who wrote The Magnificent Fire Weather, which was the book that won the Bailey Gifford last year, won all sorts of American awards. And it's about the extraordinary fire that happened in the Athabasca tar sands in the town of Fort McMurray and blazed and blazed and blazed completely out of control. And what it

told us about climate change and our world and the oil and all the various things like that. So if anyone's not read that, that's now out in paperback. The details of both the books are in the chat. And I'm going to hand over now to John. And please enjoy and please put questions in the chat because there's going to be time for them at the end. In the meantime, here we go. Introduce you both. Thank you very much for being there. Bye bye. Being here. Bye bye.

Welcome, everybody. Thank you, Rosie. And it's really a pleasure to be with you out in the ether. I wish I could be in the same room with all of you, but we're going to make do. Sunil is with us, too, I hope, Sunil Amroth, the author. And I'm looking for his face right now. But Sunil,

We're going to be talking about this book, which I felt so much resonance with and to. And so we've never met Sunil Amrath and I, but I feel a real kinship with him, with you, Sunil, already. And...

So Sunil is the author of many books, is a professor now of history at Yale, but I think was born in Singapore, has a pretty global view of things, as you'll see as we get into the book. And my first question for Sunil is, you know,

There have been many sweeping histories and recently done and well done. I'm thinking of Jared Diamond and Charles Mann and Václav Smil, all of whom have tried to kind of limb and capture this incredible period of change of the past 500 or 1,000 years.

And I wanted to ask you, Sunil, what were you hoping to add or draw attention to with this book, with "Burning Earth," that previous sweeping histories have not? - Thank you, John, and I'm so glad to be here. First of all, "Fire Weather" is a book that's just been seared into my consciousness since I read it, so it's a real pleasure to have this opportunity to be in conversation, John.

I think the main thing that the burning earth hopes to add to that corpus of wonderful sweeping histories, um,

is a vantage point outside the global North, is a vantage point from outside the North Atlantic world, which all of the authors you mentioned and all of their brilliant books, Diamond to some extent is a little bit different because as an anthropologist, Diamond has worked all over the world. But for the most part, I think the sweeping histories we have, have been told at least for the starting point in the North Atlantic world and

Both from my own biography, but perhaps more than that, from my own 20 years of doing research primarily in India and Southeast Asia, I wanted to write this global history, which does traverse really the whole world with an anchor in Asia.

And to ask perhaps which elements of the story might look a little bit different if we keep returning to Asian perspectives in particular and perspectives from the global south more broadly.

So, I mean, what I kept thinking of as I was reading, you know, I'm really anchored, you know, for good and ill in the Northern Hemisphere. But I've always been interested in maps and always been interested in turning the globe, you know, as we would say, upside down and having Antarctica at the top and Australia and the Southern Hemisphere in the kind of dominant position. That's the way we orient things, you know, in an up and down sense. And

And when you think about where Northern energy and especially capitalist and exploration and colonial energy exerted itself,

It really was heavily on the Southern Hemisphere. And so in that sense, in terms of a lens or an angle at which to look at the impact of ambition, the blast radius, if you will, the Southern Hemisphere really seems like the place to do that. And I'm wondering if...

you know, as a creature of that place, you know, as someone born there, you know, really from the opposite side of the planet from me, you know, which is kind of thrilling to consider. And here we are in the ether swirling around together with all these other people, I hope. But if you could talk more about how your country and hemisphere of origin inform your approach.

And even just quick, are there ways that it influences you that you're only just becoming conscious of? That's a great question. And the second part of that question, my answer to that is absolutely. I don't it's not until I started writing what ended up being the the preface, the prologue to The Burning Earth that I really started to make sense in my own mind of how much my experience has

the way in which I approached the story. And I'd say a couple of things. The first thing is that unlike many of the writers I most admire who write about nature, who write about the environment, I grew up in the most thoroughly urban of settings with almost no connection to what we might think of as the natural world. I grew up in Singapore at a

At a period when that city was just sort of growing so rapidly, I grew up in a high rise apartment building. I paid no attention to the natural world. I'm the least likely person to come and write an environmental history. And so in some sense,

Only later did I become conscious of the fact that my turn to my interest in environmental history began from a starting point of some skepticism, which is to say that the questions that motivated me when I decided I wanted to be a historian, that I wanted to see what we could learn from the human past. And these were questions which, broadly speaking, might be seen as political questions, questions about justice and equality, freedom and rights.

And I think growing up, I saw environmental concerns as important, sure, but probably secondary. And it's my own reckoning, I think. And some of that does come from growing up in a city where

I grew up with a sense that technology could make any problem go away. And Singapore, over the years I was growing up, Singapore's land area has grown by 25% from reclamation alone. And this is a place where, you know, through technologies like air conditioning, there's just such a sense that nature could be molded, that nature could be shaped.

Yeah. Well, and you live, I mean, Singapore in some ways encapsulates that energy and that incredible success. You know, we have to acknowledge that it was an incredible feat, you know, of resting this city that is comfortable and modern and functional and safe out of the jungle.

And it's still, you know, it has not, it did not sink back into the muck after a generation. It didn't burn. It has not been emptied by plague. It's still very vigorous. And as you point out in the book, home to the greatest airport in the world, you know, which is, you know, such a, again, a potent symbol now. And in some ways, I think you might be the best person to write an environmental history coming out of,

You're high rise and kind of discovering nature in this sort of fresh and surprising way. I mean, you're almost like a visitor from another planet, you know, in that sense, kind of stepping out of urbanity. And, you know, that's...

So I've got a question here that fits into that. So you say, when I first started out as a historian, I saw environmental concerns as secondary to political rights, economic empowerment, and social justice. I now believe that they are inseparable. And I think integration is what we do as we mature and as we learn about the world. But can you talk about that process as it

you know, impacted you and informs your work now? - Absolutely. And I think there's a particular moment where all of this started to come together in my mind. I'd been working on a previous book and that book was really more a history of human migration. It was a history of how people moving through the Indian Ocean world had sort of reshaped the cultures and societies of that entire part of the world.

I was spending a lot of time in port cities in Southeast Asia. I was very drawn to them. They're very vibrant places. There are interesting traces of history there. But this was more than a decade ago. It was about 2012. And I found myself in three cities quite close together. I was in Yangon, Myanmar. I was in Bangkok, Thailand. I was in Mumbai, India.

And I suddenly realized that just within the last few years before 2012, all three cities had experienced catastrophic flooding. The kinds of floods that would be described as once-in-a-generation floods, which had caused devastation and which were also in many ways politically engineered catastrophes, which is to say, yes, there were extremes of rainfall in each case, but what cascaded into disaster was really the lack of precaution, the

a blindness in the way that these cities were developing. And for me, that was a reckoning. That was the moment I started to say, wait a second, these questions that I'm interested in about inequality, about how these cities grow, how they're connected to one another,

is actually inseparable from the new risks that they face. And to understand those risks, I think I found that I had to then go right back and start reintegrating nature and the environment into everything I knew, which many environmental historians had already by that point started to do in really interesting and effective ways. Historians like William Cronin writing the US or Ramachandra Guha writing about India.

Yeah, but I think your awakening to it is kind of in parallel with the awakening of so many others who've also felt separate and are now...

being reintroduced to nature through these really violent intrusions that are, oh, yeah, right, you're still out there, you know, and you're not just something I go to for two weeks on holiday, but you're actually here all the time and can change the way I live. And so reading this book, I had this, you know, I felt a personal resonance because I've grappled with some of the same themes, but I also felt

heard these echoes resounding through history that, you know, and I think it was, was it Seamus, who was it who said that history doesn't repeat itself, but it rhymes. And so this kind of this carillon of history kind of banging and bonging away and the notes are almost, are so familiar. And you're starting with the Mongol Empire

And that incredible destabilization and the notion of the land as this source of energy for the horse, which animated and accelerated the advancement of those armies across Eurasia.

and their disdain for agriculture because it impacted. It basically wasn't their equivalent of an oil field, which was a meadow to feed their horses, and their horses provided them with everything they needed, obviously mobility, but also food and nourishment. So this notion echoes, and in the 14th century, these people,

terrible plagues and environmental disasters that rippled out from the Mongol Empire. And then again, in the 19th century, the turn of the 20th century, these colossal famines that, as you were just pointing out, many of them were driven, were of human manufactures.

both through by intention, but also by inattention and carelessness. And so thinking about this current moment we find ourselves in, what's echoing for you the most strongly? Where do you feel, oh, this is just like, or this really reminds me of? Yeah.

I think the idea that there is a zero-sum game for resources, that is definitely echoing for me moments from the 19th century and our last moments from the 1930s, whether that is predictions of water wars or conflicts over grain,

all of which are entirely plausible prospects. But some of it, some of that resonance, the echoing, the banging and the clattering has to do with patterns of language and imagery and has to do with the way we talk about our place on Earth, our relationship with others, our relationship with nature. There's something...

fairly unyielding and very old in some of the ways in which one continues to hear talk about energy security, talk about food security in this very exclusivist sort of way and in ways that

Definitely have resonance from earlier moments for me, no doubt. Yeah, yeah. I was really, you know, feeling so many kind of common notes and themes. And you had this line, violence, you know, was the engine of the plantation.

And when you look at more broadly at the notion of a plantation, whether it's the Mongol notion of a plantation, we're just going to turn this entire continent into pasturage for our horses and then we can plunder and burn at will. Or what was happening around the sugarcane industry and Madeira, which I'd love you to talk about in a second, is this poster child. But

Shortly after that, in the early 17th century, the American settler, New England settler, Reverend Cotton's pronounced, he that takes possession and bestows husbandry upon it, his right it is. And this notion of it almost squatters rights, you know, and even if there were people there before, if you can drive them off and hold it.

then it's yours and that's okay. And can you talk about that bizarre sense of entitlement and confidence? I think we can actually, that story starts even earlier. And the notion which has had such an incalculable impact on how we inhabit this world, the idea of wastelands, that's a medieval notion. The idea that certain lands are,

are being wasted because they're not being cultivated. I mean, you see this in medieval Europe. You see this with the Dutch reclamations. You see this with settlement east of the Elbe, this particular idea that lands, and there are versions of this in Chinese imperial thought as well, the idea that every last inch of land needs to be cultivated, needs to be put to use. Wastelands are, and therefore those who inhabit

the places deemed to be wastelands are not legitimate occupants of that land. And what's interesting to me is that that's a cross-cultural notion. You see it in China, you see it in Western Europe. It emerges at about the same time. It emerges in connection with this pan-European

pan-Eurasian and even Mesoamerican rise in state power, settled agriculture, increasing conflict between mobile peoples and cultivators. And so I think if we start there, then we start to see this idea, which then in some ways is completely manifest in 17th century in North America, this idea that anyone who's not using the land as we think they should doesn't have a right to it. And

I mean, this has further consequences and you actually write about them in Fire Weather, John, when you talk about the fact that the landscapes of North America, when the settlers are trying to understand those landscapes, they are imposing upon those landscapes very different understandings of nature and how nature behaves. And in some sense, they're trying to create a landscape in their own image. And you see that all over the world. I think that's a process you see throughout the early modern centuries.

Your book made me think anew about the definition of weeds and the things that we pull out of our garden. And even just in the, I'm looking out at my garden over the top of my screen right now. And even in the two decades that we've had this yard, this tiny little postage stamp, our notions of what we pull out of it and what we leave to grow have literally changed, have literally evolved.

and that I'm much less mowing, much less weeding, much less intervention, no pesticides.

And, you know, I'm clearly a settler on this land whose notion of what it is has evolved in just a couple of decades. And then thinking that, you know, when settlers arrived in North America, it already was planted. There were recognizable fields of plants, beans and squash and corn, you know, planted clearly and on a long-term basis successfully and broadly.

And yet there's a kind of self-serving, kind of magical thinking that, well, that's not, even though that's what sustained them and kept that, literally kept them from starving in their first seasons on that landscape, that they could somehow magically make this kind of intellectual conversion that, no, this is a wasteland and it's our job to make it fruitful.

And is that all—do you think—is religion the mask that the settler wears, or is it really a motivating impulse in terms of this notion of what a wasteland is and what fruitfulness means?

I think it's more than a mask. I think to the extent that we can think ourselves into the mindsets of settlers around the world in that period, clearly religious motivation is central in how they view the world. It's a pair of lenses. It is what motivates so much action.

And it does become self-serving because you see this again, even before the settlement of North America, you see this in the sort of double justification that are given for a lot of the land colonization projects in the East of Europe earlier, which is to say that this is for God and it'll make you rich. And I think that there's always that double sense. It's a win-win. Win-win. Yeah, right. Win-win. But there's that whole debate about,

about going back to the 60s as a...

now very widely influential piece that the medieval historian Lynn White wrote back in 1967, basically holding at least one version of Christianity responsible for the world's ecological crisis because of the emphasis on dominion, because of the emphasis on domination. And White's intention was in fact to elevate other strands of Christianity. It was not a sort of anti-religious tract. It

But in some ways, I think it's more complicated than that. I mean, some of the biggest agents of deforestation in China, for example, were Buddhist monasteries. And so there's also a disconnect between doctrine and practice. And I think one finds that in all traditions. Yeah, yeah. The...

I love islands in part because it's a way to really look at a set of processes in basically in a discrete form. And you can literally wrap your head around it. And the way you used the island of Madeira as an example of one of the first kind of boom and busts

I think it was for sugar cane and how quickly that the forests were raised, the plantations, you know,

tilled by slave labor were replaced and then exhausted themselves. And you talk about maximum profit in the shortest time, you know, which feels like another way of saying capitalism. And if you could talk some more about Madeira and what that distilled for you.

And actually, the historian Jason Moore uses that Madeira example precisely to say this is the beginning of capitalism of a particular kind. One of the things that's striking about Madeira is that the investors in those plantations were coming from all over the place. They were coming from the Italian city-states. They were coming from the Flemish lands. And so that's new, this idea of

The idea that one is trying to maximize yield of a particular crop has precedents that go long before Madeira. But the idea that this is for the benefit of distant investors and that it is to be achieved as quickly as possible, not to increase food production,

Not for any particular reason other than quick profit. I think that's what's distinctive in Madeira. That leads to the extensive use of enslaved labor, both local and increasingly West African labor. And it leads to a sort of insensibility about the consequences of

Once this is done, then another frontier will be waiting. And that's exactly what you see. You see this constant moving of the frontier lands that are ruined. And then one of the early writers, observers of 17th century Brazil,

actually made this point. He said, no, nobody looks after the land because they don't expect to stay here. And so there's something very profound, I think, in that insight from a contemporary source in the 17th century, suggesting that because the expectation is of maximizing quick profits, that changes one's relationship to the land. Yeah. Over and over again, reading this book, I kept thinking about the Alberta tar sands.

And what an incredibly destructive project it is and how nobody intends to spend their days there. You know, it's really I'm going to spend my prime working years here, make my nest egg. And, you know, I was thinking about the South African gold mine, you know, the African labor force there.

They're cheerfully toiling away, you know, in these deadly mines and then heading back to their villages with wages scant as they might be, but that were comparable to a chief where they came from. And it's so similar to Canadian workers going back to their, you know, moribund fishing villages in Newfoundland.

with these incredible salaries and often incredible debts and sometimes a drug habit to boot. And so they need to keep coming back. So it really felt like, my gosh, this 500-year-old pattern is continuing to play out. And that's where I found myself asking, wondering why isn't neoliberalism called neocolonialism?

In some places it is. So there's something, there's a line from Fireweather, John, which you use, which has really stuck with me. And that is that emissions are what you call the ultimate act of colonization. And I thought that was just such an interesting way of thinking about it. Yeah.

Because in some ways that's exactly right. That's right on so many levels. First of all, it's a colonization of the future.

But it is also an act of colonization because the cumulative effects, even though they affect every part of the world, affect very disproportionately those who've had very little contribution to those emissions in the first place. And so whether we're talking about neoliberalism writ large or specifically the sort of intensified and continuing fossil fuel emissions that we witness all around the world, I think the

language of colonization is a useful one, and it's one that certainly environmental activists have deployed at various moments since the 1980s and 1990s. It becomes more difficult because

Now the culprits are everywhere or the colonizers are everywhere. The colonizers include the elites of the global south. The colonizers include. So in that way, that language of colonization, I suppose, makes it a little bit more difficult to capture the fact that this is about often about social inequality within nations as much as it is about global inequality across different parts of the world.

It seems like the ends, though, are the same when you look at the rising oligarchy in the United States, which was, you know, for so many for so long, you know, this land of opportunity where anybody could have a chance and we could all, you know, get rich together again.

And that's just grown more and more starkly not the case. And so more and more, especially as I worked on fire weather and looked at the tar sands, it really made me see colonization. And just in terms of social changes and awareness with first the rights of First Nations in Canada,

the notion of the colonial project, it feels very present and very much alive now. And the accelerant for that, there are a couple of them, and I've just been reading Michael Pollan's Your Brain on Plants and his wonderful chapter on caffeine, which I urge everybody to read after you've read The Burning Earth, is he talks about caffeine and sugar together being this accelerant

for human labor and also focusing the human intellect. So in a way, what I'm working my way up to is fossil fuels and this decoupling that you talk about and how these accelerants enter our system.

And sugar and caffeine entered our bodies almost at the same time that sort of paved the way for fossil fuels to enter our economic system, our social system, our transport system. And so between sugar, caffeine, and fossil fuels, coal moving into oil and gas, we entered this period of extraordinary acceleration.

And there was a symbol, and then I just want you to expound on this, from the Burning Earth is illustrated, which is really great. There's some wonderful pictures and excellent, really necessary maps in there. So thank you for those. But there's an image you have from the 1876 World's Fair. Yes.

And I think it was, and the exposition that was at the Colombian exposition and where the, the coreless engine and, and not coreless as in having no core. It was the engineer, Mr. Corliss from Rhode Island who built this absolute colossus of a steam engine that's housed in its own hall in your image or that you're, you're reporting on the image of, of its tender sitting next to it, diminutive, uh,

reading his newspaper while this colossal flywheel that could practically power the city is whirring away behind him, kind of brought to heel, but also...

unstoppable. And I had this sense of the golem, you know, this robotic machine that we set in motion, but it's really hard to stop. And I'm just wondering if you could, I also thought of the War of the Worlds, just this inhumanly sized machine that once it gets going kind of has a

not ambitions of its own, but certainly literally a motive of its own. And that just felt like a turning point. Absolutely. And one of the things I love is the idea of Walt Whitman sitting in front of that engine and apparently, according to his companion, he sat in silence for half an hour. This is something unfathomable to his poetic imagination. And yes, I think...

I can see the reverberations of that power in so many places, including places which are a little bit removed. I actually see it in the post-colonial world in the 1940s and 50s. If we ask ourselves, you know, why do countries like India and China go headlong for these mega dams for this technology?

top-down re-engineering of landscapes, of nature, and even of people. I think it's what was unleashed at that moment in the late 19th century, the sense that there is this limitless power and we need to do something with it. And if you read the speeches of the first Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, who was a real technology enthusiast and also a committed Democrat, somebody very concerned with social justice, with economic equality.

There was the sense that there was this power that needs to be harnessed to build a free India, to build a free China. And I think...

In some ways, we can trace it back to that moment. And the fact that strikes me that even before the Corliss engine, if you read the early reactions to industrial machinery in Britain in the 19th century, it's the language of magic. So often those who are observing it, it's the language of magic. Even those who were deeply suspicious and who deplored the social and maybe even environmental effects that this technology was having, it was the language of magic.

And in a way, we use that language now to talk about AI as something unstoppable, something that has been unleashed. I think some of that magic is the magic of forgetting and forgetting the labor, forgetting the toil, forgetting the trauma. And Jeff Goodell...

who wrote The Heat Will Kill You First, he talks about air conditioning, which was central to the success of Singapore, you know, which raised you, that he talks about air conditioning as a technology of forgetting.

Because it enables you to hold the reality of the world or certain aspects of it at bay. And you invoke another aspect of that forgetting through William Cronin and this forgetting of the landscape. And to me, air conditioning is a technology of forgetting, but the real...

engine, the real magic of forgetting is in fossil fuels. And that goes back to this idea that you brought up in the book of decoupling, of no longer are we solely at the whims of nature, solely at the whims of, you know, if our horse comes up lame or not, solely at the whims of

You know, this this field is played out and we we have no good fertilizer for it. You know, we can we can now override all these natural systems with petroleum products. And this this notion of forgetting, which I think, you know, the forgetting will get us killed, you know, if we don't remember. And and I'm wondering if you could just talk about that as a theme in your book.

That's a wonderful way of framing it, I think, John. And in fact, I think the last sentence of the book, I think, has to do with remembering, because I think in some ways the whole of The Burning Earth is a history of forgetting. It started out with my trying to reconstruct where does this idea come from that we are outside nature, that we are not subject to its constraints and its limitations.

that idea has always been a fiction or a fantasy. And yet it's had an incredibly firm hold on a significant part of the global imagination for coming onto a century now. And it doesn't seem to be going anywhere. I think there is still just that very powerful desire to forget. And you see that in the day-to-day life of our cities, right?

You know, you talk about this when it comes to Fort McMurray. It's as if it was subverting the laws of nature, is how you put it, John. And there are so many cities that are doing that. Dubai is doing that today. Las Vegas is doing that today. Singapore, in some ways, is doing that today. And those cities go on. Those cities thrive, many of them, and they keep growing. And then the question is, well, how long can this forgetting go on?

And that is why very often it takes more and more infrastructure, more and more technology, more and more technologies of insulation to keep that fantasy alive. And clearly many of these cities are coming up against those limits. They're coming up against rainfall even greater than anything that they planned for. They're coming up against fire. They're coming up against the realities of what we've done to nature, to this planet.

That this idea of forgetting, and we build in a forgetful way. And what I'm curious about, and this is somewhat outside the purview of your book, but someone with your scope, I think all of us would benefit from your answer to this. Why are we so willing to forget? Why are we so eager to forget? And here's a very modern example of

The Google map and many people now, if I'm I still ask people for directions and everyone pulls out their phone. Very few people know the streets that are around them or know what they connect to.

And, you know, the old British taxi driver test where, you know, you basically had to know every alley. You know, it's an incredible mental map that the British taxi, the London taxi driver had to carry in their head. And all of us used to have that for our home place, you know, wherever we lived. And we don't very much anymore. And there is, why are we so willing to relinquish that, do you think? Yeah.

It's so disempowering, ultimately. Probably because I think initially it feels empowering to be unencumbered by that, because the smoothness of the technologies that we rely on will do this for us, will

in a utopian way, sort of free up our minds to do or think about other things. Though in reality, what it's doing is it's actually sort of tethering us more and more to those technologies, which we can't do without. And I think the more dependent, and that's true at every level from the Google map to the so-called technosphere that sort of sustains all of these cities that we live in, which is that the more we depend on them,

the more catastrophic becomes the potential consequence of those technologies breaking down. And so there is this, to use a completely different kind of example, I mean, Pakistan is a country that has suffered such catastrophic flooding, you know, twice in the last 15 years.

And it has almost always been the case in those instances that the most heavily engineered environments suffered the greatest damage. Because when those finely engineered landscapes failed, that amplified and multiplied the damage. And I think we can take that finding, which is at a different sort of scale, and think about all of our lives and the fact that there is a cost to our forgetting. The benefit of the forgetting is convenience. And maybe it's as simple as that. But...

there's a cost which probably lies around the corner in many cases.

I mean, I think we're kind of living that right now. And I invite all our listeners to consider that. And it's something I really wonder about in myself. And Timothy Snyder, who wrote On Freedom and many other relevant books today, he talked about how much we're losing now. And not in terms of freedom, perhaps, but also just in terms of

what we give up of the power of our own intellect by just engaging with machines as we do. And it's anyway, that's a long conversation. And early on in The Burning Earth, you talk about this charter of the forest.

And and this this ire, you know, this this gathering where people just talked about, you know, what it meant. And and maybe you can sum that up quickly for us. And so.

Are the Rio Earth Summit of 1992 or the 1997 Kyoto Protocol or the 2015 Paris Agreement or the current ongoing obligations of states in respect of climate change unfolding right now at the Court of Justice level?

Are these latter-day charters of the forest? And are these hopeful signs? Are these a way of kind of integrating and grappling with some of the questions we've been talking about? So just to go back quickly to the Charter of the Forest, of course, this is the companion piece to the much better-known Magna Carta. And the Charter of the Forest, it would be anachronistic to see it as a charter for environmental protection. I think what it is more is it's a statement that...

People's livelihoods depend on nature and on being able to access, but also protect and preserve the health of what we now call ecosystems. And then there were these forest courts, these ayahs, which would hear cases and which occasionally did rule in favor of commoners.

who wanted to use the royal forests, who wanted to assert their rights to common property versus those who would enclose. This is the sort of early history of enclosure. What was interesting is that these were legally enforceable provisions. And I think that's what's very different from some of what we are dealing with now.

I would not say that there hasn't been progress, that even statements of principle at an international level, I think have been very important since the late 20th century. Without them, we would be even further steps back than where we are. But the problem has always been enforceability. And that's true even when it comes to the Paris Accords. It comes when each country comes up with its nationally determined contributions, those are effectively voluntary. And, yeah,

That leads us to the question of the mismatch in scale between the scales of our institutions, particularly of our democratic institutions, imperiled though they might be, and the scale of the problems that we face. And I think that disconnect is one that we're all grappling with in different ways.

Yeah, we sure are. I've got one more question for you, Sunil, and then we'll open it up to our audience. And I see us now kind of inhabiting this tension between a comment that you attribute to George Bush. I've heard it was Dick Cheney back in Rio in 1992. The American way of life is not up for negotiations.

And I think, I think Rumsfeld may have parroted that and Cheney, you know, all those guys, you know, you know, it's not negotiable. And, and,

You know, and it feels like the U.S. is kind of retrograding, you know, regressing back into that, leaning back into that. And but there's a new not new, really. It's an ancient, but it's a revived way of thinking about our place in the world from the 2008 Constitution of Ecuador, in which it articulates, you know, effectively Mother Earth and

has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions, and evolutionary processes. And I feel like, you know, it's like the devil and the angel on our shoulder. And what do you see? What do you see for us? You know, scientists talk about

tipping points that we may be close to that we may in some cases already have crossed. And I suppose the question is, are there also tipping points in human consciousness? And are there tipping points in our ability to come together? And I think the burning earth and fire weather both take some comfort towards their final pages in the sense that the fossil fuel industry, for example...

is on the run. I mean, can no longer hide behind the misinformation, behind the propaganda. There is so many new efforts to hold to account those who continue to sort of accelerate emissions.

They're all subject to reversals. I was very struck by the Australian judgment that you quote, John, and then the fact that it's overturned just a year or two after the judgment is made. So these are halting progress, but-

I don't think there's a single movement in the world that mobilizes more affiliation and energy than the environmental movement writ large. For all of its setbacks, it's relatively recent, really only emerges at least on a global scale in the 1970s. And

In that, I do see some cause for at least longer term optimism. I think we're at a very difficult moment in global geopolitics, not least in the US, but everywhere, I think, at the moment. But looking beyond that, I think there are some of these movements in the right direction when it comes to mobilization, when it comes to consciousness, when it comes to political action.

And these are generational processes. The effort to abolish slavery took half a lifetime or more before it was enshrined, and there is still slavery to this day. So it's an ongoing, and it will never be black and white or on and off. It's going to be just proportions and degrees, probably.

It's a great analogy, actually. That's a great analogy. And the same would be true of civil rights or indigenous rights or post-colonial struggles. Yeah, yeah. And again, we find surprising allies in surprising places. So I think the audience may have some questions. And Jack, do you have access to some of those?

I've posted them in the chat, John. Can you see? Okay. Okay. Taking a look at the chat here. Okay. One is, Sunil, do you see any nations or countries in particular who are leading the way when it comes to climate policy? Who are your champions? That's a really interesting question. One of the countries where the overall picture that one gets in the global north is one of alarm, and that alarm is in many ways justified is Bangladesh.

Bangladesh is very often presented as being at the front line of climate impact, and it is. And yet I've always been struck by the constructive and creative ways in which Bangladesh is preparing itself for heightened risks.

It's a little told story, but it's truly astonishing what Bangladesh has done to reduce the casualties from massive cyclones from the 1980s to now. A cyclone of an identical magnitude to that which in 1970 killed half a million people. A few years ago, the death toll was in the hundreds. And this is through completely...

mundane, if you like, measures, cyclone shelters that are friendly to women, cyclone shelters that allow people to take livestock with them.

Mobile phones to spread early warnings. Meteorological literacy that comes from being able to sort of interpret what's coming through on people's phones. Bangladesh is taking seriously the reality of climate-driven migration. There are projects to try to make second tier cities in Bangladesh more hospitable to migrants so that not everyone ends up in Dhaka.

So I think looking around the world, I think there are so many ways in which often pragmatic, not headline grabbing ways. There are countries, including countries which are exceptionally vulnerable and which have contributed very little to global emissions, are being creative and are being proactive in doing things.

That it's such a beautiful example because and again, it just makes me feel my the the imprisonment of my own geography.

And because, you know, most of the examples that I would have would be from the North. And I had never heard that one. And I'll wager most of our listeners this evening weren't aware of that. And it's so powerful. And when you think of the scale of lives saved and when you think of the inclusiveness in terms of

gender relations and the relationship to animals and realizing that, you know, this larger community all needs protection.

And so to me, that also, you know, that is a kind of a corollary to the constitution of Ecuador in a way. And so that's really a beautiful example and a very hopeful one, especially when you consider, you know, just what in many of our lifetimes, you know, the colossal losses suffered there. Another question was, reading your book made me think that it might be impossible to get

people to change as we have always been ruthless about the environment. Are you optimistic? I always feel, I think, two contradictory things at the same time, and I do actually believe them both to be true. One is that, yes, there are these recurrent patterns and

One of the things that I certainly learned in researching and then writing The Burning Earth is how enduring some of these habits of thought and behavior are and the fact that many of them are also cross-cultural in interesting ways, that it is not only the global North or the West that has indulged in some of these practices at certain moments in history.

At the same time, I think the burning earth is actually full of stories of change. Sometimes change that happens very quickly. Sometimes change which would have been unimaginable even a generation earlier, or sometimes even just a few years before it happens. And so I think there is an open-endedness

that as a historian, I continue to believe in. That's actually ultimately why I find history inspiring and instructive, and not because I think it holds lessons for the future, but because it just reminds us of how contingent and unpredictable the world is, and that can be in positive ways as well as negative ones. Yeah, yeah. There's another one here. Thank you for that. It's...

I'd be interested in hearing about how certain Indigenous cultures, presumably consciously, dealt with things in a different way, avoiding the forgetting and keeping humans closely linked to nature and how we can draw on that now. I think, John, you'd be as well-placed to talk about that from a Canadian point of view as I would. And in fact, I might ask if you have thoughts to begin with.

Well, sovereignty and the reestablishment of sovereignty. And that's a headline issue in Canada, which is really amazing because we still have, we now have the king on our money, but we had the queen on our money for a very long time. And yet the legal issue and the practical issue of indigenous title is

This reclaiming title to vast tracts of Canada is happening literally as we speak. And many of the First Nations in Canada never signed treaties. So this is the most of us in Canada are living on technically unceded territory. We're basically occupying it.

And that is in the court now and having real impacts in terms of who takes over going forward, managing really large landscapes and all the activity that that takes place there. And so there's an opportunity in that I see for a reset.

and re-education, and it's actually happening around fire, where we're realizing, you know, through a century of fire suppression in North America, which was driven by, you know, settler violence,

priorities and objectives, but it was also a way of suppressing indigenous practices, not just language, not just religion, but actually ways of being on the land, which included regular low-level burning in the spring and fall. And that was lost, partly through smallpox and war, but also through active suppression. And now,

foresters, fire scientists are realizing we need to have that fire back on the land. And so prescribed burns are becoming a regular practice in basically forest hygiene across the continent. And the First Nations who are still on that landscape, who still have fire traditions, are now being partnered with, with fire scientists and firefighters to

to have this integrated approach to basically

redress and recalibrate this terrible imbalance in fuels and ways of being on the land. So that is, you know, it's an ongoing project into the future. And I think as these groups get to know each other again and the hierarchy becomes more horizontal as that dissolves and we realize, you know, what we've lost, that it's an act of humility that

And but also a real act of self-preservation. You know, that is a real win win. And that is happening now. California is one of the leaders, but it's also happening in Western Canada and even even in some of the eastern states in the United States. So but I'd love to hear that.

what you're observing. And just two things. First is I think exactly the same is true in other parts of the world, that when it comes to the question of, well, how can we elevate and amplify the traditions of thought and environmental practice, which in some ways have been sort of lost by most of us? Well, sovereignty and land rights are a crucial first step. And the same is true in Indonesia. The same is true in many parts of Southeast Asia that start with land rights, start with

tackling the question of dispossession and its legacies, only then can we reset. And I like that idea, John, of a sort of more horizontal footing, but there are preconditions for a more horizontal footing within which different groups and different traditions of thought can get to know one another again. The other thing is, on a hopeful note, I think...

you think of the kind of translational work that someone like Robin Wall Kimmerer is doing. I mean, Braiding Sweetgrass is probably the most influential environmental text of the last decade or so. And it's all about translation. It's about building bridges. It's about finding ways in a non-exploitative and a non-instrumental way to sort of learn from other traditions, including traditions that have never lost what many of us, I think, have lost. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

I think that's a beautiful note to end on. And we've both invoked some wonderful books and some wonderful reading. And what a wonderful pleasure to speak with you, Sunil. Thank you, John. It's been a treat. Yeah, no, really. For me, too. And thank

It's a really powerful book. And I had the thing I wanted to say, too, was it was a little bit like watching that Reggio's film, Koyaanisqatsi, this kind of acceleration and reading The Burning Earth was phenomenal.

was, you know, this kind of breathtaking and breathless tour of the last 500 years. And it reads very quickly. It is absolutely fascinating. I learned so much. And I study this, you know, basically for a living. And I still was taking notes, you know, like Rosie Boycott was. And you've really, you know, contributed something wonderful. And thank you so

much for that and thank you all for coming everyone out there yeah so good to be with you all