Shownotes Transcript

Hey, it's Nancy. Before we begin today, I just wanted to let you know that you can listen to Crime Beat early and ad-free on Amazon Music, included with Prime. The following episode contains descriptions of sexual violence and may not be suitable for everyone. It also contains coarse language, adult themes, and content of a violent and disturbing nature. Listener discretion is advised.

In the late 1970s and early 80s, a sexual predator lurked in the shadows and left an entire city on edge. The city was kind of going nuts. There were multiple reports of an unknown man exposing himself to both women and children, and police said some reported being violently sexually assaulted.

Investigators believed the same person was responsible and that they were looking for a serial rapist. The big thing about what was happening was a lot of midnight break-ins and sex assaults. And then there were similarly going on at the same time events involving children, youngsters. Youngsters were being attacked online.

on the street and a very, very, a very elusive person at the time. You know, they were in different locations, but you had to know the, by the MO and after the interviews with the victims, you had to know there's a link there.

I'm Nancy Hixt, a senior crime reporter for Global News. Today on Crime Beat, I share the devastating story of what happened and the steps investigators took in solving these crimes. This is The Hunt for a Predator. Before I begin, a warning. This story includes graphic details of sexual assaults and violence against children.

In the spring of 1980, Calgary teachers walked off the job in one of the longest strikes in the city's history. The job action impacted more than 80,000 public school students who no longer had classes to attend. Two of those kids were Olivia, who was 11 years old and would have been in grade 5, and Emily, who was 10 and would have been in grade 4 had school been in session.

I'm not using Olivia and Emily's real names for reasons that will soon become clear. On one particularly nice June afternoon, the two young girls took advantage of the unexpected early summer break to go for a bike ride in the southwest part of the city. Olivia's bike was a blue 10-speed, and Emily rode a blue 3-speed.

They got onto a popular bike path that winds along the Elbow River and rode to the Glenmore Reservoir, a man-made lake that supplies Calgary's drinking water. It was about a 10-minute ride from their neighborhood. They took their time and stopped to throw rocks in the water before hopping back on their bikes. On their way back home, they cut off the main bike path and took a dirt trail up the hill.

That's when seemingly out of nowhere, a man appeared. He grabbed Olivia, the older girl, and put a knife to her throat. The man told her she better listen and threatened that the two girls would get it if they didn't comply. Olivia started to cry and told Emily to listen to whatever he said. The man took the girls by their hands and walked them into the nearby bushes.

The little girls were terrified. I need to warn you, what happened next is horrific, and I'm only going to share details that are absolutely critical to the case. Olivia watched as he blindfolded her friend with a towel. She took note of what he was wearing, jeans and a red, blue, and white checkered shirt.

He then asked Emily if she could see anything. She said no, but secretly, she was able to peek under the edge of the cloth. That's when Olivia made a move. She tried to run, but he quickly chased her down. He held his knife to her legs and threatened to kill her.

He made her lie down and sexually assaulted her. When he was finished, he went over to Emily, took off her blindfold, and put it on Olivia. Then, he sexually assaulted Emily. When their attacker finished, he warned them not to tell or he'd come after them. He told them to start counting as he ran away. After a few minutes passed, the two girls ran to Olivia's house.

Both in tears, they told their parents, who called the police. I was in Court of Queen's Bench. I was testifying in a major offense there, a jury trial. And I got a pager message to go to an address in southwest Calgary where two young girls reported being attacked.

Jack Mullins is retired now, but in 1980, he was a detective with the first-ever Calgary Police Sex Crimes Unit. We had the interviews at the house. I got some statements. I asked them if they would write out on paper what they saw, what he looked like, this guy, and how they came upon him.

Detective Mullins has a clear memory of his interview with the two little girls. They're children. They're just kids. They're, yeah. They were on their bikes. They were down by the park and they got intercepted by this fellow. And he had assaulted them. He said the girls provided remarkably clear descriptions of their attacker.

They were very brave and very astute. And I remember the one little girl saying to me, you know, I peaked. I lifted the blindfold and I peaked. Am I going to be in trouble? I said, no, you're not in trouble. No. And I remember that. Little girls, so brave, those little girls, you know, what they did that day. It was a very, very...

moving interview with those two little girls. The detective was convinced these two children could help police. I left these little girls with my card, my business card, and I said, "We're getting really close to finding this guy. You might see him around." And I do remember, I do remember telling them that if you could keep your eyes peeled and if you see him, phone me and here's my card.

Both girls were taken to hospital where they were examined. Their clothing was collected and became evidence in the sexual assault case. Meanwhile, investigators began their search for the attacker. And then I went over and had a look at the scene where this occurred and got some pictures. And I had the identification branch come out and take some pictures for me.

Hours later, Emily returned to the spot where they were assaulted. She walked investigators through the area and provided further details. Given the brazen daylight attack, police felt the offender was likely the man they had previously dubbed the Southwest Calgary Rapist. I got to assume so.

only by virtue of the same kind of events, the same modus operandi, the same operating the same way. At the time, there was a long list of crimes police were investigating and attributing to the Southwest Calgary rapist. Some of those include an attack in October of 1978. A 17-year-old girl was grabbed from her yard. The man used a knife to threaten her.

He put goggles over her eyes, dragged her to a playground, and attempted to rape her. He forced her to perform various sexual acts and then attempted to rape her again. A few months later, in January of 1979, a 27-year-old woman was grabbed. The man put a knife to her neck, put goggles over her eyes, and attempted to rape her several times. In November of 1979,

An offender broke into a school, grabbed a woman working in the building, and blindfolded her with a scarf. He dragged her into a room, attempted to rape her several times, and when he wasn't able to complete the assault, he fled. As this predator lurked, investigators noted that with each case, the offender's violence escalated.

And now, he was threatening to kill victims if they didn't cooperate. What no one knew at the time was the worst had already happened. Five months before Olivia and Emily were attacked, in the same community where the Southwest Calgary Rapist attacks had happened, a five-year-old girl disappeared on her way to school. Altador is an inner-city Calgary neighborhood.

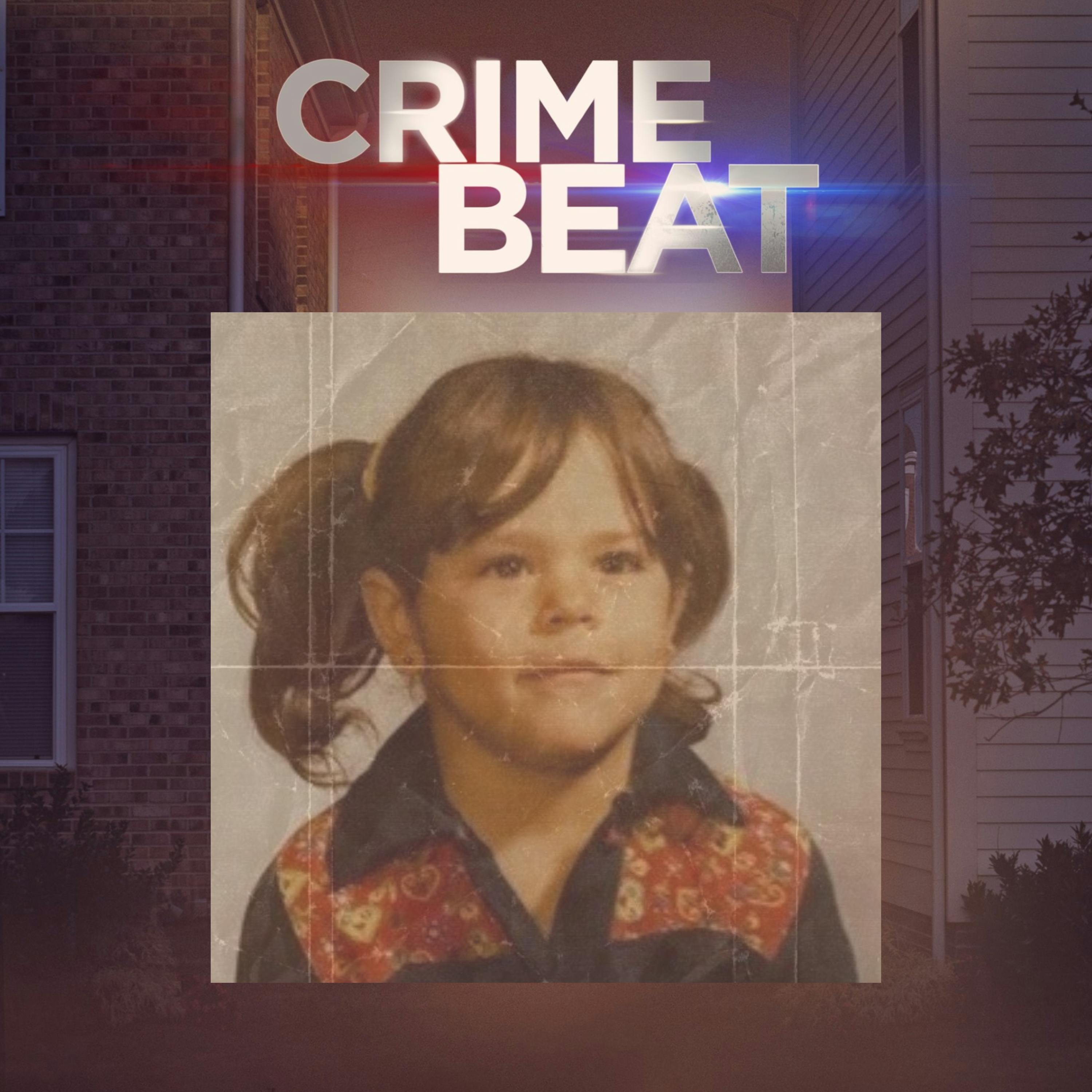

In the 1980s, the relatively quiet community neighboring a military base. It has beautiful recreational areas, including Sandy Beach along the Elbow River. And there's a popular bike path that follows the river there as well. This is where Kimberly Thompson, affectionately called Kimmy, grew up. Here's her mother, Evelyn Thompson. She was a happy little girl. She loved her jewelry.

You know, she loved being around people. Yeah, she just, she was just happy. She was a beautiful little girl, big brown eyes. Five-year-old Kimmy was the youngest of Evelyn's three children. She just loved her picture being taken. And anytime I tried, she would crawl towards me. So you could get the pictures, right? She loved hanging out with her brother and sister and her cousins.

In a photo taken in the fall of 1979, Kimmy had her long brown hair in pigtails. Her mother told me that particular photo was a big deal because it marked the beginning of kindergarten. She was loving school and everything seemed to be going really well. Until I had a conference with the teacher and she told me that Kim was too dependent on me.

At that time, Kimmy was about a month short of her sixth birthday. So that I should let her do things on her own. So that was the first time I let her go to school on her own. I had my reservations and I thought, no, you know, that's not a good idea. But then I thought, what do I do? So I figured, OK, I'll try it.

Evelyn Thompson remembers those final moments before Kimmy walked to school alone for the first time on January 24th, 1980. She had on dark blue dress pants and a red turtleneck sweater with yellow socks. Evelyn made sure Kimmy was bundled up. She had on a blue snowsuit with a red and white scarf, a green hat with brown and yellow and white on it, and of course, she was wearing her winter boots. So,

When she was going, she had left all her mittens at school. So I said to her, you know, make sure you bring your mittens home from school. And she, you know, I said, and go straight to school, you know. And I watched her till she got to the corner. And then I went back in and I had, I was babysitting at the time, my niece and nephew. The walk to Altidore Elementary School was only about six blocks. And then at lunchtime,

The other kids came home and my niece, she said to me, "Auntie, where's Kimmy?" And I looked at the clock and it was like quarter after 12 or something. So I ran, I ran to the school and I went in and I checked her room, the kindergarten room, and she's not there. I went to the office and I said, you know, "Where's Kim? Kim Thompson?" "Oh, she didn't make it here today." I thought, "Oh Jesus."

Oh Jesus. So I, on the way home, I ran and I stopped at all her little friend's place that I knew where she might go and nobody had seen her. So when I got home, I was so rattled that I couldn't even remember the phone number to the police station. So I had to call my sister and I said, you know, what is the number? Well, why? I said, because Kimmy's missing. She didn't make it to school today.

Friends and family retraced Kimmy's steps, but there was no sign of the little girl. I was just terrified. And then the police came and, you know, set up a command center outside and they started searching. Friends of ours from the military came over. They helped. They were searching. Friends walked around the neighborhood searching. I was... And it got later and later and later.

And I was standing at the window about, I don't know, 11 o'clock at night. And it was snowing. Oh, it was snowing big snowflakes. Her disappearance triggered a round-the-clock search by 60 police officers, the military, and more than 100 concerned citizens. As the hours passed, Evelyn said hope of finding Kimmy safe faded. And I just had this overwhelming feeling.

that I was never going to see her alive again. She was living every parent's worst nightmare. They told me not to leave the house. So I stayed, and there were people around. My dad was there. My partner was there. And I think it was around, and I don't know the exact timing, but I think it was around noon in there, when a police officer came in. He said, he said, we found her. We found her body. And I just...

I'm not even sure if I collapsed or not, but I could feel my knees going out and my dad had one side of me and Dawn was on the other. And I don't really remember much after that.

Their worst fears were confirmed just 24 hours later when the little girl's nude frozen body was discovered in a garbage bin only blocks from her Altidore home. The girl's body was wrapped in a garbage bag, piled in a fence line garbage container just four blocks from her home. On the ground, detectives began piecing together the grisly facts.

Detective Daryl Wilson became the primary investigator assigned to the case. I got the phone call, said, you've got to come to work. We've got a homicide of a child here. So that's how it all started for me in the afternoon of January 25th, 1980.

Detective Wilson is retired now, but he was with the Calgary Police Service from 1967 to 1994. The first step is to sit down with the family members and discuss the situation with them. You know, what was a normal day? Who was around her? What were her normal activities? Who lived in the home with them? All of those sorts of things and those sorts of people that were involved with her had to be ruled out.

He told me that it didn't take long to clear Kimmy's mother and family members as suspects. But Evelyn said when no one was immediately caught and charged in the case, many people wrongly assumed her family was responsible. They blamed me. They thought that I had killed her. And then it wasn't me. It was Dawn or her biological dad. My kids were bullied at school.

That assumption weighed heavily on her as she tried to cope with the devastating loss. As the search for the killer continued, detectives hoped an autopsy would provide insight into what happened to Kimmy. The medical examiner concluded she died from asphyxia, from either smothering or drowning, and noted there was water in the little girl's lungs.

At the autopsy, police also collected forensic evidence. Back in those days, as a homicide detective, you did a lot of your own forensic gathering, whereas that wouldn't happen nowadays. So it was necessary for us to very slowly collect evidence from Kimberly's body. There was many, I can say there was certainly many hairs and fibers that were located on the body and removed by us.

The samples were sent to the RCMP crime lab in Edmonton, but results would take time. Right, it was frustrating. And there was another issue as well, and it was made public. Not that we particularly wanted it made public, but that was the clothing was never found. The outfit that Evelyn had carefully picked out for Kimmy before sending her off to kindergarten that morning was missing.

That included her pants, turtleneck sweater, her yellow socks, the snowsuit, hat and boots. It kept coming up on the news and we still don't know what happened to the clothing in this case. Then, five days after Kimberly Thompson's body was found, there was an anonymous phone call to a nearby grocery store. And told them if they went to the dumpster they were going to find clothing.

And so of course they did, and one of the people that worked in the grocery store happened to be the son of a police officer. So he phoned his dad right away and said, "Hey, you know, this has happened and what do we do here?" So his father told him how to collect the evidence and to just leave it as best he could, not handle it. Investigators carefully examined the items found in the garbage bag.

The clothing matched what we knew about Kimberly's body. Again, we're back to these hairs and fibers. Everything was, in fact it was our staff sergeant at the time that went and retrieved the bag and laid it out, examined it, removed what he could from it. And the rest of it was packed up and it was actually sent or taken to another crime lab in Toronto by one of our detectives.

They were hoping for fingerprints. They had a new system for fingerprints, removing fingerprints back in those days. Unfortunately, no fingerprints were recovered. But with this new evidence, investigators worked around the clock to solve the case. They knocked on every door in the neighborhood, hoping to find witnesses to Kimmy's abduction and murder. Nobody, nobody said anything. Nobody saw anything. It's amazing.

Kimmy Thompson's case became a true whodunit. I can't tell you the amount of pressure it put on me and my superiors. Every day they were wanting updates and wanting news, what's going on with this case? So my superiors were then coming to my partner and I and, you know, what's going on? And have you done this? Have you done that? And as we know, investigating a homicide is a slow process. There's no shortcuts.

Detective Wilson and his partner came up with a cutting-edge strategy that involved a dog, and it played a critical role in the hunt for a predator. It wasn't just our family, it was the whole neighborhood that was in fear. I'll never forget it. You know, like I said, I had children my own, similar age. It was a difficult case.

Until the day I die, I'll never forget. It makes me sick, actually. Sick to my stomach. Because I'm so, so afraid that it's going to happen again to somebody else. And nobody, nobody should have to go through what our family's gone through. That's next time on Crime Beat.

Crime Beat is written and produced by me, Nancy Hixt, with producer Dila Velasquez. Audio editing and sound design is by Rob Johnston. Special thanks to photographer-editor Danny Lantella for his work on this episode, and to Jesse Weisner, our Crime Beat production assistant. And thanks to Chris Bassett, the VP of Network Content, Production and Distribution and Editorial Standards for Global News.

I would love to have you tell a friend about this podcast. There are five seasons of stories you can listen to and share. And if you can, please consider rating and reviewing Crime Beat on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen. You can find me on Facebook at Nancy Hicks Crime Beat and on Instagram at nancy.hicks. Thanks again for listening. Please join me next time.