Chapters

Shownotes Transcript

Support comes from Zuckerman Spader. Through nearly five decades of taking on high-stakes legal matters, Zuckerman Spader is recognized nationally as a premier litigation and investigations firm. Their lawyers routinely represent individuals, organizations, and law firms in business disputes, government, and internal investigations, and at trial, when the lawyer you choose matters most. Online at Zuckerman.com.

Does your morning toast taste more like cardboard than bread? Then you haven't tried America's number one organic bread, Dave's Killer Bread. Killer taste, killer texture, killer nutrition. Now try our new Rock and Rolls, a dinner roll done the Dave's way. Soft and slightly sweet and packed with the seeds and grains you love.

Find them in the bread aisle. Visit daveskillerbread.com to learn more and look for Dave's Killer Bread in the bread aisle of your local grocery store. Dave's Killer Bread. Bread Amplified. This autumn, fall for moth stories as we travel across the globe for our main stages.

We're excited to announce our fall lineup of storytelling shows from New York City to Iowa City, London, Nairobi, and so many more. The Moth will be performing in a city near you, featuring a curation of true stories. The Moth main stage shows feature five tellers who share beautiful, unbelievable, hilarious, and often powerful true stories on a common theme. Each one told reveals something new about our shared connection.

To buy your tickets or find out more about our calendar, visit themoth.org slash mainstage. We hope to see you soon. Welcome to the Moth Podcast. I'm your host for this week, Edgar Ruiz Jr. I'm really excited to introduce to you two special guests that we have on today. They are the host of one of our favorite podcasts, Ear Hustle, Nigel Poore and Erlon Woods. Say hi. Hey, what's up, witch? How you doing? Hello. Very happy to be here.

So Ear Hustle is one of those podcasts that so many people at the Moth are kind of in love with. For people listening to this who might not be familiar with the program, can you talk about what Ear Hustle is and what stories it shares? Sure. You want to start, E? No, no, dig in. All right, all right. So Ear Hustle is a podcast about everyday life in prison.

told from the perspective of those experiencing it. Erlon and I started working on it together in, what, 2015? Pretty much, yeah. Yeah, when Erlon was incarcerated at San Quentin. I always forget how long your sentence was. I don't know why. Maybe I just want to forget it. Yeah, it was two life sentences. So, yeah, he was serving a life sentence, and I was a volunteer at the prison, and our original idea was to create a podcast that would air inside all of the...

prisons in California. That was our big dream. But before we hit that dream, we started airing the podcast outside of prison. And it just grew from there. Everyone outside got the ear hustle. And then Erlon, your sentence was commuted in 2018. Yes, 2018. Because of the podcast. Yeah. And since then, we've been telling stories outside and inside of prison. And now we get to do things like this, get to talk to you about the moth.

together. We get to talk to the storytellers. Exactly. It's great. This is really in alignment with our work at the MOF. I'm the manager of the community engagement team, and we get the privilege to work with a lot of incarcerated and post-incarcerated folks, helping them share their stories. In fact, stories all about the prison system have been a big focus of our community storytelling workshops since 1998. And it's really cool to be in a conversation with you both today. So this is going to be a little bit of a special episode.

We'll be starting off by hearing an excerpt from the Ear Hustle podcast and then following that with a story from the MOF that feels related. Nigel, Erlon, can you set this up for us? In particular, can you tell us what Bonnaroo means? So Bonnaroo is a term. I don't know who created this term, but what it is is it's when you are all creased up, matching, you look like you ready to go to the club.

That's what Bonnaroo is. Your shoes are shined. Your pants are creased. Your shirt is creased. You probably got a cool little haircut to go with it. But when they use the term Bonnaroo, that's what they mean, that you came out for business. And I mean clubbing business. The clip that we're about to hear is from an episode called Tax is Tripping. And, Nigel, what is that episode? I mean, what is...

Okay, so this episode, well, this clip from Taxes Stripping is about how do you, well, can Bonnaroo be a verb? How do you Bonnaroo in prison? Is that a verb? Can you Bonnaroo? So that's what this clip is about. I mean, it's a big deal in prison, right? You usually have to, well, not usually, you have to wear a uniform and you're supposed to look like everybody else. So one of the interesting things is how do people push back against that and find workarounds

To look Bonnaroo. To show their own identity. Exactly. Show their own identity through how they physically present themselves. And this particular clip, I think, has everything that an Ear Hustle story strives for, which is it's looking at a serious topic, but it also is being done with a little bit of humor, introspection, and surprise. Now let's take a listen to Ear Hustle. What did you have for breakfast this morning? I had a honey bun.

You start your day with that much sugar? Yeah. I work it off, but yeah. How old are you? I'll be 34 this September. Okay, that's why he can do that. After 40, you can't start your day like that. No, it stays with you for the rest of your life. Nobody should start their day like that, but I mean, I'm in prison, so I've earned that. This is Tax. New York and I talked to him a while back in San Quentin. How many honey buns do you eat a week? I think I did probably somewhere along 13 a week.

That's twice a day-ish. By the time you get out of prison, how many honey buns do you think you will have eaten? Let's see, four years. We'll go over 1,000 for sure. Let's just say that. Was this going to be a honey bun interview? No, no. I want to ask you about what you— I mean, we could make it one. I've got some honey bun stories.

I was going to ask, Naj, is this actually an episode about the honey buns and I didn't get a memo? Don't you wish it were? Yeah, because I would have been like, we're going to put that Antoine song up in here. So the breakfast thing is just the standard question we ask people when we're setting their mic levels. We actually asked Tax down to the studio to talk about clothing and about a particular piece of clothing he saw when he first got to San Quentin. I came to this prison January 2019.

One of the first things I saw when I got off the bus was somebody in a bomber jacket. If anybody knows what a bomber jacket is, they're pretty stylish. Almost Letterman jacket type. They're fitted. They're tailored around the bottom. Also around the sleeves and on the collar. And I thought they were prison issue. Yeah. I've seen the actual prison issue jackets, and they are nothing like what he's describing.

If anybody knows what these CDC are, blue jackets look like they're pretty crappy. They look like a mix between trash and a raincoat. They snap up the front. They're just like wearing a shapeless blue thing. Windbreaker. I wouldn't say shapeless. It's like a rectangle feeling going on. Almost like you're wearing a stiff dress. Yeah, it's not flattering. Those bummer jackets on the other hand, though, they fit right.

I was like, "Well, how do I get one of those?" Because that's what I want. And you couldn't find it. Nobody would tell you anything. It's kind of pretty hush-hush. It took me almost a year to figure out where I could get this jacket.

We should tell them why this is so hush-hush now. Yes. Well, what we're talking about is upgrades. Pretty much. Upgrades to a standard set of clothing the state gives you when you get to prison. And that includes stuff like T-shirts, boxers, pants, and shoes.

Right. And that's state property. And the state doesn't want you messing with it. And they definitely don't want you altering it so much that you can blend in with civilians and walk out the front gate. That's what's called escape paraphernalia. Yes. But that bomber jacket, I don't want to say it's escape paraphernalia per se, but Erlon, it's a pretty big alteration. It's nice. Definitely.

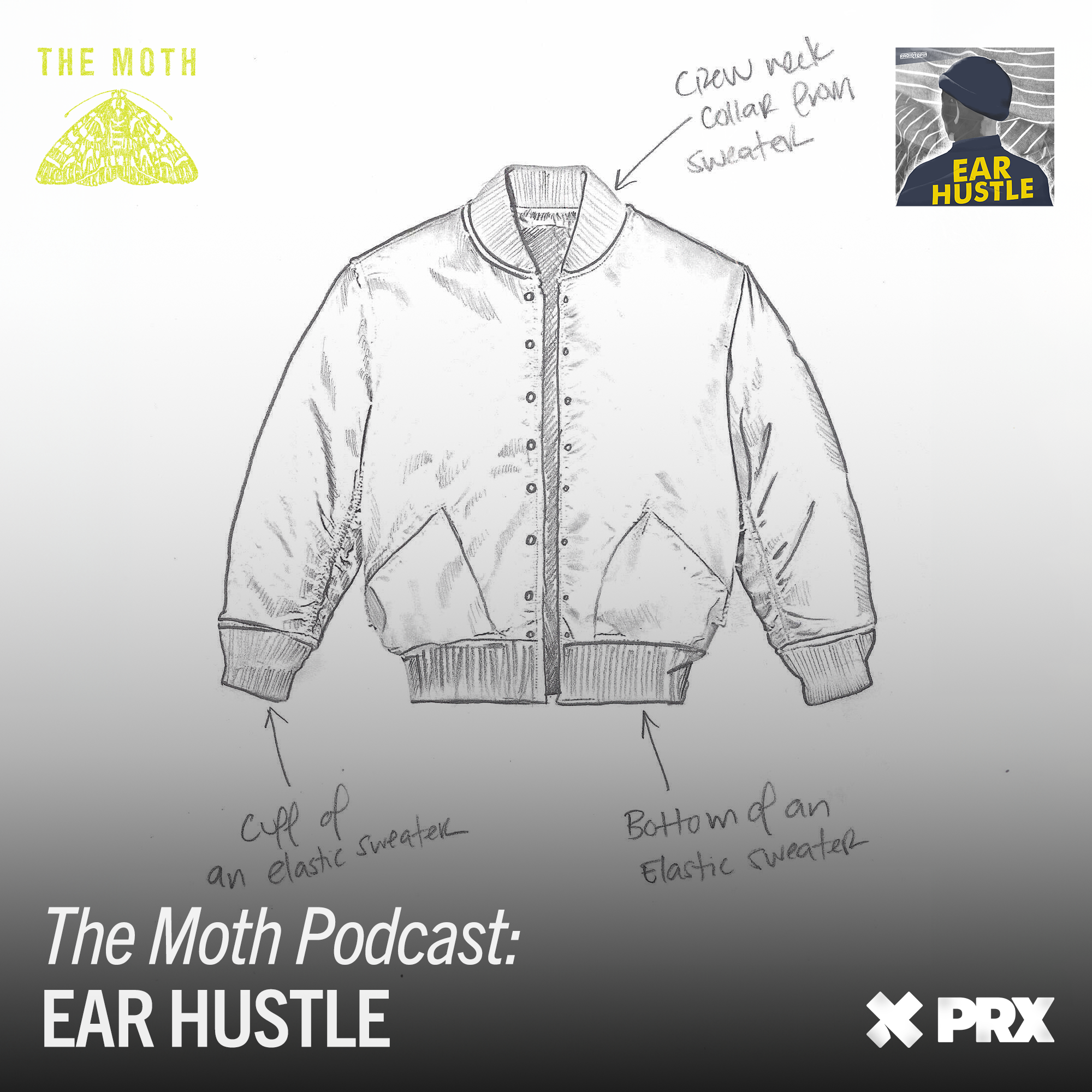

It is nice. And this is what they'll do. They'll take the elastic collar, the cuffs, the waistband from a state-issued sweatshirt and sew those into a state-issued windbreaker. And you'll end up with this cool-looking giddy-up, you know, that kind of looked like a bomber jacket, top gun. Nice. What was it, Goosenim? Philippa and I have never seen that movie.

And Tax really wanted one, so he kept asking around. And finally, a year after he saw that first one, Tax sees a second bomber jacket. He knew that he was about to go to visiting, and he wanted to be styling for the pictures he'd take. So he talked to the guy with the jacket. I was like, hey, can I wear your jacket? Oh, for the picture. For the picture. Yeah. Took a picture in it. I liked the picture. I sent it home.

My family was like, "Oh, I like your little jacket." I'm like, "Yeah, me too." Putting that jacket on, did it bring back any memories or feelings? It just made me feel like I was not so much in prison. On the streets, I dress a certain way. My clothes are fitted, tailored. I don't wear anything that's oversized or undersized. I'm not a baggy clothes wearer.

You kind of get that nostalgic feeling. Like, you know what? I miss how I look. And that's one thing about prison. It made me feel like I'm bummed out. I'm not me. I don't look like me. You kind of want some semblance of normality. So as much as you can escape this place, that's what I was feeling. Like, you know...

"Alright, hey, I'm looking good. Alright, I like this. What do I gotta do to get this jacket, man? Yeah, do I gotta sell my soul or anything like that?" He says, "You know what? You like that one?" I'm like, "I do." He said, "Just take it."

In return, Tax gives this guy the materials he needs to make himself a new bomber jacket. So Tax has this jacket. He loves it. And he makes a vow to never part with it. You couldn't grab this jacket without me noticing. I will absolutely not let this jacket go. It's going to stay with me until I leave here, at which point I will probably choose very carefully who I give it to.

So one day I'm asleep. It's early in the morning. I hear, and I'm going, what the fuck is that? This is Jesse. He was Tax's bunkie at the time. And I look up and there's two cops. He goes, which locker is yours? And I went, oh, no. And I'm thinking, I'm going to the hole. My stomach sinks. I'm like, oh. I go, this one. He goes, well, good, because we're looking for your bunkie. And I said, oh, no. He goes, well, look, you can pack his shit up or we can do it. And I said, fuck. I just got up. I said, let me get it. I'll take care of it. Tax was headed to the hole.

And when you get sent to the hole, all of your stuff gets packed up, and then the officers decide what they're going to let you have. So Jesse was packing up all tax stuff, and he was trying to do a nice job with it. Yeah, I mean, E, we've talked about this on the show a lot. You're a bunkie or celly, that's an important relationship. Hell yeah. And Jesse says tax was a good bunkie. I know his character. I know his program. Comfortable, that's a big thing in here.

My TV got Fox, which shows Friday Night Wrestling. So I'd come back from group on Friday night. He'd be sitting on my bed watching my TV with a bowl of deli bites and a little rice bowl with some sweet and sour soy sauce and stuff hoisin' and a Pepsi for me going, and he just pointed at the TV. - Oh, wait, we have it ready for you? - Yeah. And he'd have his bowl with his Pepsi, the splitter cable coming off for his headphones. He's watching TV.

And he looks at me and he's like, and he just pointed wrestling like it's on. And I knew already, like, all right, just sit down and eat and watch the wrestling show. You know what I mean? I mean, can I just say that's really sweet. Yeah. So that's, you know what I mean? That's his character. So all the important stuff, TV, watch, radio, fan, you know, all these important items. Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. I'm getting them in there. I started packing this shit up. Nothing was in my mind except what the fuck happened. Where's he going? Goddamn. That sucks. All that kind of shit.

It wasn't until later that day that Jesse realized the one thing he'd forgotten to pack. The whole bed was empty. Everything was gone except that jacket was hanging on the end of the bed. And I remember looking at it and I said, oh, his jacket. So I went to the officer who packed up his stuff and I said, hey, is he coming back? He goes, I think so.

So Jesse tucked that jacket away in the safest place he could. But days went by. Tax didn't come back. A month passed, two. COVID happened, and things started to look pretty bad. It hit the six-month mark, and somebody was like, hey, man, what's up with tax? Is he coming back? And I said, I don't know. Let me go check. So I went to the only officer I know that I have a good rapport with, like that anyway, and I said, hey, is he coming back? And he goes, no.

He goes, I don't think so, man. I think it's been too long. I think they're going to ship him out. And when he said that, I walked back and I took the jacket, right? Literally, I put it on to just try. I was like, I'm going to wear it. I'm going to wear this fucking coat. You hadn't worn it? Not once. Not the whole time. It just sat there the whole time. Didn't wear it. It was underneath my jacket. I don't even wear a jacket to chow. I'm Canadian. It ain't cold out here to me. I walk in the rain to chow. I don't care.

I put the jacket on, and he's taller than me, so it kind of, it don't look right. It don't look like a bomber. So the dude next to me, he saw me with it on. He goes, hey, what's up with that jacket? Let me get it. And I was like, ah, that's my bunkies, man. He was like, what's up with him? Is he coming back? I said, no. He goes, let me get it. Who cares? I said, well, if he does come back, I need the jacket back. You didn't sell it? You just gave it away? No, yeah. I just wanted to see somebody wear it, like, and enjoy it.

How long were you in the hole? Six months. Oh. Yeah, I was gone from my jacket for six months. Erlon, literally three days after Jesse finally gives away... It was just a temporary loan. Okay. So three days after he temporarily loaned Tax's jacket out, Jesse sees Tax on the yard, fresh out of the hole.

I saw him on the yard and the first thing that popped up, the only good news I could tell him was, "Hey, I still got your jacket." "Hey, your jacket's still here." When I heard it was still here, it was kind of like, "Oh." And he just snapped his facial expression, went, "Go get it." "Oh, you have the jacket? Yeah, I don't care about anything else but the jacket. I want the jacket."

Only problem is, Jesse doesn't actually technically have the jacket. Right. He had given it to another guy, and that guy had spent those three short days he had the jacket washing it. I mean, kind of obsessively washing it and making it his own.

He washed the shit out of it, right? Used state soap the first time. Then he used laundry detergent the next time. Tied. Then he used Gain the third time to make it smell good. Hung it up and dried it. This was a Saturday, Sunday. He came back on a Monday. The jacket literally was just like fresh from the dry cleaners. Somebody else had the jacket and he took care of it. He washed it and everything. I was like, wow, you know, okay, cool. But I want it back. Like, just give me the jacket back.

I said, "Well, I gotta get it from the neighbor 'cause he just washed." He goes, "Well, go get it." And I said, "Well, he's asleep right now." "Well, go get it." It was apparent that I wasn't going to get the jacket back for a while. At which point, I kind of flipped a switch. Were there some strong words you used? They were interesting words, I'd say.

What I said along the words was, I'll be in there later to get that jacket. And I fully intended to go in there and get the jacket. Before I could get back to the building, I bent the corner. I heard, hey, I need that jacket, man. I'm going to get my jacket. If I don't get that jacket back, I'm coming up in there. And then I heard this little screeching voice go, Jesse, Jesse, Jesse. I was trying to calm Tex down until he got the jacket back.

This is Quincy. He was a screeching guy. Right. He was yelling at Jesse to hurry up and get that jacket while he tried to keep tax calm. And he was livid. Oh, my God. Look, I'm going to let you know this right now. Pack up my stuff if I'm going to the hole. I was like, you just got here. Let me get this straight. You were ready to go back to the hole where they would not even let you have the jacket for the jacket. Yes.

And so me being the Christian man that I am, I was like, Tax, let's just pray about this, man. Lord, we come to you and Tax is tripping and we want to calm him down. So any way possible, if you can de-escalate this and bring him back his jacket, send that jacket back in Jesus name. Amen.

So Jesus got him his jacket back, right? Well, actually it was Jesse. I gave this dude laundry soap for a month. I gave him like $2 in food, like a dollar and a bar of soap. Oh my God, he never let me live it up. So if you gave it to the guy, why did you have to pay to get it back? Because it was like I'd be stealing it if I didn't compensate him for his time and his effort. But what about the fact you made a contract, a stipulation that if your bunkie came back, you need the jacket back?

He did not remember that in that moment. But you had kept it for five months and 30 and 27 days. And then three days after you gave it away, tax comes back. Literally like Jesus out of the tomb or something. Quincy, the guy who prayed to the Lord while tax was tripping, he and tax did become friends. And Quincy says now he never sees tax without that jacket.

If you had to speculate, why is this jacket so emotionally important to him? Seeing everybody in blues, and a lot of people do wear them, you start looking like the other person. And then all of a sudden, you know, everything is monochromatic. You know what I mean? It just looks—everything looks the same. There's no standout. And I think this made him stand out. And it gave him a sense of freedom, you know? And he was going to get that freedom back.

That was a clip of the Ear Hustle episode, Tax is Trippin'. You can find Ear Hustle wherever you get your podcasts. We also have a link in the show description. Up next, we'll have a moth story that also deals with adaption and getting along with people while incarcerated. But first, I wanted to talk a little bit more about Ear Hustle itself. Walk me through the process behind telling stories within a prison. Mm-hmm.

Oh, that's a that's a that's a long process. I would I would say first, you know, of course, we have to identify a story or a theme that we want to talk about. And then we have to find the individuals that's going to be able to articulately talk about that.

What the story is. So usually we would either, you know, do it by word of mouth, asking individuals or, you know, when I was incarcerated, we used to put up signs on the walls in the buildings where, hey, do y'all have anything in common with this? Can y'all come talk to this? And some people will come down.

Well, it's interesting when we started, when Erlon was still inside, people didn't know Ear Hustle. And so he was constantly Ear Hustling trying to find stories whenever he was standing in line somewhere. And we had to do a lot more fishing, I guess you would say, to find people to talk to us. But after Ear Hustle came out and it started playing in all of the prisons and people could hear it, it sort of shifted. Now people come to us a lot with ideas for stories.

What specific challenges did you face? I could imagine putting this together isn't easy.

It was huge. I mean, imagine when you're in prison, you have no internet, you don't have phone access, it's very hard to print anything, you don't have all of the programs you have on your computers out here. So we were transcribing things by hand at first. Yeah. Once I left the prison, I had no contact with Erlon. So I was in there working all the time. We worked probably 40 plus hours a week, but we had to be really scheduled and on

on point about what needed to be done when I was out there, what I had to accomplish out there, what he had to accomplish inside, and then what we were going to do when we were inside the prison together. There could be lockdowns where I couldn't get into the prison for weeks. I think maybe there was one time when it was a month. I mean, anyone in the prison administration can change their mind and say, no, this isn't going to happen. So we had to tread lightly and

Be really determined and do what I call the three P's, patience, politeness and persistence to just get things done and not get frustrated and really support each other. Definitely, because the one thing that is always going to be unpredictable and that's whether or not it will be normal program the following day. Mm hmm.

You know, and that's the one thing that, you know, nobody controls because, you know, you have, of course, 4,000 personalities that's in that prison. And, you know, one of them could do something that, you know, jeopardize the program of everybody else, you know. We don't have to be this way now, but for the couple years, I can't remember how many years it was before. It was like two years we were working on this inside prison.

I left every day knowing I might not see Erlon for a while. And so we both had to have that frame of mind that it wasn't like, OK, I see you tomorrow. We hope we see each other tomorrow. But that wasn't a given. Never a given. What do you think the role of storytelling is within a prison? Me personally, I think storytelling, I don't want to say I don't want to say necessarily accountability. I just want to say storytelling opens people up.

to a conversation that they don't usually have, you know what I'm saying? Or, or stuff that they don't usually tell or especially, you know, the way that, that we do stories, you know, um, people get to speaking on stuff that is really dear to them, that they knew, they knew it was in them, but they never really exposed it. And I think, you know, that's too, for me, that's, that's part of the storytelling process. Um, it's really getting something out of people that either they never, uh,

Talk about comfortably, comfortably. Is that the word? Mm hmm. That's how I see it. A lot of times, you know, people really when you when you when you having conversations and telling stories, people say some stuff that, you know, will take us aback, you know, and like, damn, that was deep.

Yeah. I mean, I think storytelling in prison or really anywhere is, and when you're, it's the telling the story, but it's also somebody listening. It needs, there's those two components. And when you're telling a story and you know, someone's listening to you, it's a way of saying I exist and I matter. And it's a deeply emotional and pivotal experience for a lot of people who feel like they haven't been heard before or haven't been considered. And

I'm sure this happens on the moth when people are telling the story and they realize that they've got undivided attention. It's a boost to one's self-esteem and creativity and sense of well-being. I think it's an essential experience for people to have. Awesome. Thank you for sharing that. When people listen to Ear Hustle, what is something that you want them to come away with?

There's a big list here. Go Ian.

And prison, of course, are the marginalized population. But, you know, we're able to at least, you know, bring their stories to people. Every time we put a story out, the one thing I always like to see and hear from people is this is my new favorite story. Yeah, we do hear that a lot, which is nice. I want people to.

when they hear our stories to think about who's in prison in a different way. I want them to think about the responsibility they have as taxpayers to know what's happening inside prison. I want them to see the commonalities between life inside and life outside. I want both sides, the people who are telling the stories and the people outside listening to feel empowered to make change. I want people to be entertained and amused and intellectually and emotionally challenged and

I love when a story makes people think in a new way. So when we started doing the podcast, we did get a few kind of eyebrows raised that we used humor in our podcast. But I think that's really important. I want people to understand that

you know, just because someone's incarcerated, it doesn't mean their whole life there is a flat line of frustration and anger. There's so many, of course, you know, life in there is like life out here. You're going to have all kinds of experiences. And so I think having the humor and the curiosity and the creativity that comes across in the people that we interview is really important. And I want that to come across in the stories too. Thank you so much for the work that you do. This is important work. Thank you so much. Thank you.

Up next, we've got a Moff story from Derek Hamilton. We met Derek when he took part in the Moff Community Workshop with the New York Innocence Project. He told the story you're about to hear in a showcase for those justice-related stories. The show was intimate and mostly invite-only, which is why you'll hear a small but mighty crowd cheering him on. Here's Derek live at the Moff. In 1992, I was convicted of murder in a Brooklyn courtroom. I was sentenced to 25 years of life.

I was sentenced to a maximum security prison throughout New York State. I spent 10 years in a special housing unit. In any yard I watched Training Day, Denzel Washington said 23 and 1 in the SHU program, Pelican Bay, that's where I lived. Some of the most inhumane treatment you can imagine. Prisoners banging on walls all night, yelling and screaming, feces being thrown on inmates, urine being thrown on inmates.

The only one piece in solitude that I had was two law library books that came every day from a prison guard. You had 24 hours to study the book and learn all the knowledge that you could in that little period of time before you had to turn it back the next day. The banging, the screaming, the yelling interrupted me. There was a guy on top of me by the name of Spud Webb who we all had came to the conclusion was insane. He was extraordinarily the most insane person in that special housing unit.

None of us wanted to talk to Spud Webb. When he would get in the movement, he would curse you out, derogatory names that made no sense. This day, after enduring six hours of banging and yelling, I convinced myself to get down on the vent and yell up to Spud Webb. We would yell through the vent to have conversations with each other on the higher floors because there's no other way to communicate. People would call me for legal questions and I would answer them. So this day, I knelt down and I said, "Spud Webb!"

Remind you, Spud Webb banged all day. So I timed that he would stop for about 30 seconds and then he would go right back. So I had to get Spud Webb in his 30 seconds when he was tired. Then I had to have a compelling argument to Spud Webb why he should stop banging. So on this day, I yelled again, Spud Webb! Spud Webb! Spud Webb! And he said, what? And I said, can you stop banging? And he said, no. You read law books. I bang.

Banging is my livelihood. I had no fight left. I had to think a little bit. I said, this guy's not insane. He seemed to be the smartest one in this conversation. I pondered and I said, what should I say to Spud Webb? So I said, Spud, well can you lower the banging down a little bit? Don't bang so loud. He says, I'll try.

For that moment, I felt that I had a victory. I had Spud Webb willing to try not to bang so loud. So I learned something that day. I learned that we perceive people to be a certain way based on prejudices and institutional biases. That Spud Webb, like me, was living in inhumane conditions, and he found banging as a way to escape it.

And if it wasn't for his banging, Spud Webb would have been dead from suicide or some of the other things that we've seen. So I had empathy for Spud Webb, even though he banged. And from that moment, I looked at him through different eyes. And that is my story. That was Derek Amaker. Derek is the deputy director of the Pearl Murder Center for Legal Justice at the Cardoza School of Law in New York City.

While wrongfully incarcerated, he taught himself law and worked on both his case as well as helping other prisoners with their cases. He's also the legal director of Families and Friends of the Wrongfully Convicted. Through the years, we've worked with many different justice-related partners to develop and showcase these stories that sparked much-needed conversation.

The MOF's partnership with the Innocence Project and the Innocence Network actually goes back almost 20 years. And they are one partner in our growing network of collaborators. To find out more about the MOF's work with people involved with the criminal legal system, go to themof.org. Well, that's all for this episode. Thank you so much for joining us, Nigel and Erlon. Thank you very much. We appreciate it. Yeah, thanks for having us and great, great, great conversation. Thank you.

Before we leave, is there anything you want to say about Ear Hustle to the Moth listeners? Yeah. Start at the beginning. If you've never heard Ear Hustle, start at the beginning. And I'm going to appreciate you for sharing it because once you listen, you're going to share it to your closest friend. I guarantee you.

First of all, I love the moth. I love listening to moth stories. I love thinking about the listeners that are in the audience taking in what's happening. So I hope that our stories can offer that same experience to the moth community. If they take a listen, they'll feel the same kind of connection they feel when they listen to a moth story. You can listen to Ear Hustle wherever you get your podcasts. We also have a link in the show notes.

And keep an eye out for a really great Moth story on Ear Hustle. That'll drop July 10th. From all of us here at The Moth, have a story-worthy week. Edgar Ruiz Jr. is the manager of the Community Engagement Program and a Story Slam host at The Moth. He is a comedian and storyteller who has been featured in The Moth's latest book, A Point of Beauty, true stories about holding on and letting go. This episode of The Moth Podcast was produced by Sarah Austin-Ginness, Sarah Jane Johnson, and me, Mark Sollinger.

The rest of the Moth's leadership team includes Sarah Haberman, Christina Norman, Jennifer Hickson, Meg Bowles, Kate Tellers, Marina Glucce, Suzanne Rust, Brandon Grant Walker, Leigh Ann Gulley, and Aldi Caza. The Moth would like to thank its supporters and listeners. Stories like these are made possible by community giving. If you're not already a member, please consider becoming one or making a one-time donation today at themoth.org slash giveback.

All Moth stories are true, as remembered by the storytellers. For more about our podcast, information on pitching your own story, and everything else, go to our website, themoth.org. The Moth Podcast is presented by PRX, the public radio exchange. Helping make public radio more public at prx.org.