Chapters

Shownotes Transcript

Hi, it's Phoebe. We're heading back out on tour this fall, bringing our 10th anniversary show to even more cities. Austin, Tucson, Boulder, Portland, Oregon, Detroit, Madison, Northampton, and Atlanta, we're coming your way. Come and hear seven brand new stories told live on stage by me and Criminal co-creator Lauren Spohr. We think it's the best live show we've ever done. Tickets are on sale now at thisiscriminal.com slash live. See you very soon.

The first contact was a knock on the door on a Saturday when I was sitting in my dorm room early afternoon. I was doing, you know, I was studying and there was some knock on the door, which I knew immediately that there had to be a stranger because another student, when they knocked, they would come right in. It was 1970 and Jack Barsky was studying chemistry at the University of Vienna in East Germany.

But at the time, his name was Albrecht Dietrich. So I said, come on in. And in came a short individual with a cast on his left arm. And he introduced himself as a representative of a local optics company, which actually was one of the few companies in East Germany that made stuff that could sell in the West. It was high-precision optics companies.

And he then said, "I just want to talk with you about your plans after you graduate." And that was like really dumb. He should have known that in those days companies did not recruit. There was no sense in speaking to me. So I immediately figured out he's probably East German secret police and let's see how this is going to evolve.

Jack says that they made some small talk about his plans to be a professor after he graduated. And then, suddenly the man asked if Jack could ever imagine himself working for the government. So we had some communication between the lines, and he invited me to lunch at the most expensive restaurant in town. And as I enter that restaurant, I see the fellow sitting at a table, and there's another man sitting there.

As I walked slowly towards my acquaintance, he got up and came to me and he said, "Let me introduce you to Herman. We are working with our Soviet comrades." And then he excused himself. And so that's how I wound up having a relationship with the KGB. I'm Phoebe Judge. This is Criminal. Jack Barsky says that from then on, he started meeting with Herman all the time.

Every Monday at 8.30 a.m., he would call Herman and learn when and where they'd meet. It was always somewhere they wouldn't be noticed, Herman's car or a safe house. And Herman would tell Jack everything he knew about how to be a spy. Eventually, Herman decided Jack was ready to try some small things on his own.

So for instance to go knock on a door and some house and talk to the resident and find out something about a relative who lived in West Germany. I hated that task but I did well. I got the information. I pretended to be a sociology student and I wanted to ask her if she would participate in a short survey.

And I had some made-up survey questions, and then sort of I turned this into more of a social talk. And I mentioned some, you know, relative I had in the West, and before you knew it, oh, you have one too. Another time, Jack says he was asked to find out what was inside a commercial building in town. So another little trickery, a ruse, there was a bus station next to that building.

And I left a package on the bench in that bus station overnight and then picked it up, made it disappear, and then I knocked on the door of that building and asked them, did you by any chance remove that package?

What package? Well, you know, there was like this important package. And I said, you know, just like there were some writings in there that I'm preparing for my thesis for my diploma. And he said, well, I can't help you. And then I managed to, it was lunchtime. He says, you want to go to lunch? And so it became again a social event. Jack believes he was being evaluated all this time.

evaluated to see if he was trustworthy enough and good enough to take on bigger responsibilities. After about 18 months of training, Herman sent Jack to Berlin. He told him he would meet with a handler there and gave him the time and location and a secret code to use when they met. Each of them carried a sports newspaper in their left hand so they could recognize each other. Jack approached the man and said, Excuse me, I'm looking for Lindenstrasse.

The man responded with the correct code. Is that where Helmut lives? And then they were safe to introduce themselves. After that first contact, they met every three days. At one point, the handler, whose codename was Boris, arranged for Jack to cross over from communist East Berlin into West Berlin for a day to, as Jack put it, get my feet wet.

Jack remembers that after he got back to East Berlin, Boris asked to meet. He told me, oh, by the way, we're going to take you to speak to somebody important. So it was this huge building. I didn't know what it was. I found out later on it was the headquarters of the Soviet Army in East Germany and the headquarters of the KGB. And he took me to a long, long walkway inside, dimly lit. He took me to an office building.

And there was this little man sitting behind a huge desk. And this man spoke only Russian. So we had a little conversation back and forth with some translation. I had enough school Russian to understand most of what he said. And it was a bunch of like small talk about, you know, the cause of communism and what we were doing. I didn't need that. But I nodded and whatever. And all of a sudden, he changed his tune and he said, all right,

"Here's the question: Are you in or not?" And I was not prepared for that. He knew he would have to give up everything he'd worked for: a career as a chemistry professor at his university, his friends, his name. He would have to disappear from his life. And no one, not even his mother, would know where he was. Jack remembers his contact in Berlin, Boris, saying, "As far as most people are concerned, you will have vanished into thin air."

Wherever you go, you'll be in hostile territory. You will have to befriend your enemies and pretend to be one of them. And so... But then there was the lure of going to the West and being a hero for the communist cause. At that point, when he asked that question, I just stalled. I said, "I can't give you an answer now because I don't know if I qualify. And secondly, I'm not trained at all."

And then he said, "Well, trust me, you qualify." We determined that. And secondly, we will train you, but we only work with people that can make good decisions very quickly. So I give you until noon tomorrow to give me a yes or no. That made for a sleepless night. And I went back and forth in my mind, back and forth. And I tried to, you know, make it like weigh the two paths on a scale that didn't work.

Eventually my instinct said, "I gotta do it. There's a chance of a lifetime." So I told Boris the next day, "Yeah, count me in." We also had an East German version of James Bond

It was an illegal agent sent from the East German secret police into the West to hunt down Nazis and he changed his identity and he became a different person. And he also lived the good life, the James Bond type of life where fast cars and nice houses. And that is what I thought the kind of life I would live. I would have my cake and eat it too, do great things for the communist cause and

and lived the rich life of the West. He began with more training. There were two major elements of the training. The best training I got from the KGB was what we call tradecraft.

all the tools that you need to know and all the ways that you communicate and how you operate and how you behave, meetings and handing over materials and Morse code and encryption, decryption, secret writing, photography. That took a lot of time and that was in-person one-on-one training.

Then there was a part of the training that was fundamentally up to me. I was told to, you know, broaden my knowledge of culture, of literature, of music, just to become, you know, a very, very well-educated, all-around educated person who could operate in higher strata of society. He went to museums. He took himself to the opera.

And he was told he had to learn another language. He picked English and got very good at it. And then the KGB informed him that he would be going to the United States. At the time, the relationship between the Communist Soviet Union and the United States was tense. And each country was using its intelligence agency to try and get more information about the other. One way the Soviet Union was trying to get information was

was by sending secret agents to the United States to set up lives with fake identities. Were you excited when you heard that you were going to be going to America? Absolutely. You know, I wanted to travel the world, and the United States was like, it couldn't have been any better.

I knew that the United States was our main adversary. We called it adversary, but fundamentally it was close to being an enemy. And for me to go to the United States that is like, my God, the most powerful nation in the world, and I would help bring that country down. Can't get any better than that. Because, you know, I was very ambitious. Jack went to Moscow to learn how to blend in in America. He met with a U.S.-born tutor to practice his English.

And he worked with a husband and wife named Morris and Lona Cohen. Both Lona and Morris were born in America. When they married in 1941, Lona didn't know that her husband was already a spy for the Soviet Union. But he recruited her, and they quickly started working together. Lona had helped sneak the blueprints for the atomic bomb from a contact at the US lab at Los Alamos to the Soviet Union. She hid them in a tissue box.

They came close to being caught in New York in 1950, but were able to eventually make their way to London and start new lives working as booksellers. They were arrested for espionage in 1961. Investigators found a radio transmitter hidden under their refrigerator and tiny photographs of secret documents hidden in the spines of antique books. After eight years in prison, they were sent to the Soviet Union in a prisoner swap.

They lived in Moscow, where they were treated like heroes, and where they showed Jack Barsky how to talk and act like an American. For the final step in his training, Jack was sent to Canada as a kind of dress rehearsal for living in the United States. Before he left, a contact from the KGB gave him his first pair of Levi's so he would blend in when he got there.

I acquainted myself with the richness of life materially, especially in North America. He remembers watching television for hours, including sitcoms and Sesame Street. He was fascinated by The Price is Right. He ordered the same breakfast every day, an order that he'd been told was the usual for Americans. Ham and eggs over easy, whole wheat toast, a glass of milk, and a cup of coffee.

After he returned from Canada, he was told that the KGB had found an identity for him to use in the United States. He was given an American birth certificate with the name Jack Barsky. So the birth certificate was a certified copy of the birth certificate of Jack Barsky, who was born in 1944 and passed away in 1955.

In those days, it was possible to acquire a birth certificate of anybody, regardless of whether you... You didn't have to show that you had a valid interest in that birth certificate. So there was one of those diplomat agents wandering around one day at a cemetery outside of Baltimore, and he found Jack Barsky's gravestone and acquired that birth certificate.

To fill out his American identity as Jack Barsky, he began to practice the made-up story of his past: places he could have lived, schools he might have attended, a farm in upstate New York where he could have worked for a few years. For more personal stories, he used his own memories and focused on switching the names of his German friends for American-sounding names. To explain what remained of his German accent, Jack planned to say that his mother grew up in Germany.

We'll be right back. Support for Criminal comes from Ritual. I love a morning ritual. We've spent a lot of time at Criminal talking about how everyone starts their days. The Sunday routine column in the New York Times is one of my favorite things on earth. If you're looking to add a multivitamin to your own routine, Ritual's Essential for Women multivitamin won't upset your stomach, so you can take it with or without food. And it doesn't smell or taste like a vitamin. It smells like mint.

I've been taking it every day, and it's a lot more pleasant than other vitamins I've tried over the years. Plus, you get nine key nutrients to support your brain, bones, and red blood cells. It's made with high-quality, traceable ingredients. Ritual's Essential for Women 18 Plus is a multivitamin you can actually trust. Get 25% off your first month at ritual.com slash criminal.

Start Ritual or add Essential for Women 18 Plus to your subscription today. That's ritual.com slash criminal for 25% off.

What did you tell your family before you left? Oh, what I told them? That I was recruited to work as a chemist in Kazakhstan, where they had a highly secret space research and rocket launch place that was not accessible to anybody unless they had a permission. And that also had no phone lines in and out of the place.

So I was fundamentally unable to communicate directly. The only way I could communicate was with letters. He pre-wrote generic letters and postcards that would be periodically sent to his mother during the years he would be away and unable to communicate with her. What did you say in the letters? You know, nonsense.

you know, like stuff that, you know, daily life, you know, small talk and writing, you know, I made it up. It was painful to do, but, you know, I was ill or I fell. I had my wisdom tooth pulled. I was talking about some colleagues and on and on and on. Eventually, we changed our method of operation. And so I, rather than handwriting, I

In 1978, Jack left for America.

He took a complicated route on planes and trains through Belgrade, Rome, Vienna, and Mexico City, so no one would be able to figure out that he'd come from Moscow. He says he spent a brief time in Chicago, and then he went to New York. I landed at LaGuardia Airport and took a bus into Manhattan, and I was thinking, oh my lord, these avenues and streets are so narrow. Fifth Avenue is not narrow. Madison Avenue is not narrow. But...

The buildings that line those roads are so high, it looks like they're squeezing the roadways. In Moscow, the big, big roads, for instance, in and out of the airport, were lined by four- to five-story buildings, and they appeared a lot wider. So that was my first impression. How did you set up a life for yourself?

Well, the first year when I didn't have documentation, I spent in a rather somewhat sleazy hotel, but you could blend in because nobody asked you any questions. You paid with cash, it was no problem. And I also made sure that there was no suspicion by staff. And every morning I left at a certain time and every evening I came back to sort of...

feign that I had a job to go to. So I spent the days in town. And my first job, like, I couldn't get a really good job because I couldn't take... I wasn't able to bring my past with me. So I couldn't, let's say, go to university and say, you know, I want to be an assistant professor. So I picked a bicycle messenger. So as a bike messenger, my colleagues were all transient workers. You know, they...

They were in and out of the job and they didn't care to ask questions. So I spent a lot of time in the office when I was waiting for another delivery to be made, just listening to them. Learning about baseball, learning about what they watch on television, learning about the movies and watch them and how they gestures and everything and it absorbed a lot of things.

What were you supposed to be doing? Okay, so there was the explicit mission and there was the implied mission. The implied mission was to just live there and become an American because there was concern that during the height of the war that eventually diplomatic relations would be broken up altogether. And then the only ones left, so to speak, behind enemy lines were us illegals.

Spies like Jack were called illegals by the KGB. So the explicit instructions were, well, you know, you need to become an American and get to know as many people as you can and find out if they, first of all, people who are maybe working in government or having an influence on government decisions, and also people that we might want to recruit. In addition to getting to know as many people as possible,

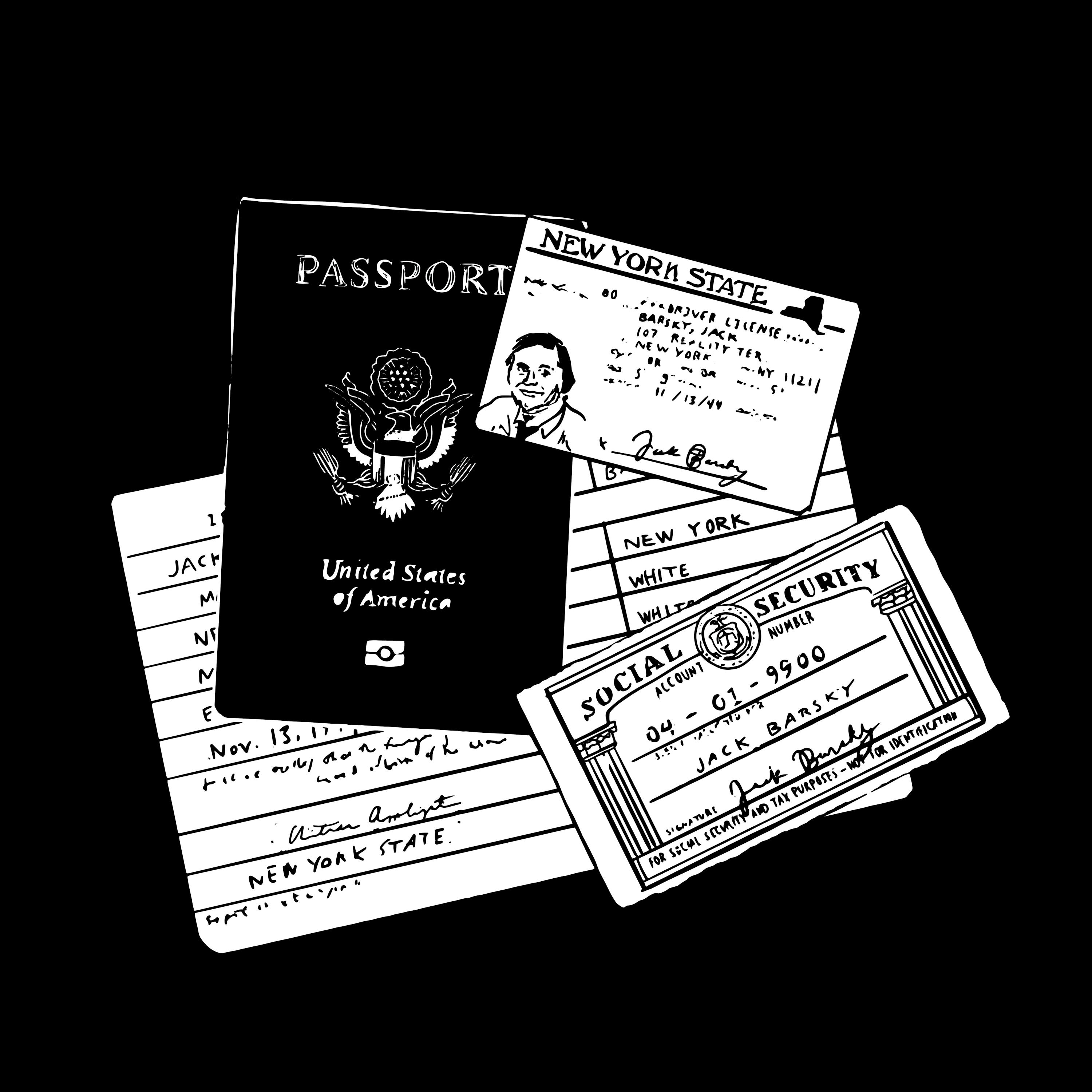

Jack was also supposed to be getting his documents squared away, a driver's license, a social security card, and ultimately, and most importantly, a U.S. passport. All he had was the birth certificate for Jack Barsky, but he'd been given instructions for how to use it to get started. And the instructions didn't work.

You needed to get a driver's license, you needed a birth certificate and some kind of ID that showed where you lived with name and address. And they told me, "Just get a library card." So I went to the library in Brooklyn. I filled out an application and said to the librarian, "Can I have a library card?" She looked at me and says, "Do you have ID?"

"Oh, sorry, yeah I do, but I don't have it with me. I'll come back." Now I'm caught in what they call a catch-22, so you gotta have ID to get ID. That was a dead end. I reported this back to Moscow and they had no idea how I could get out of that quandary. And it took me a lot of research. I went into libraries and looked at all kinds of books and I read newspaper ads and I just tried to figure out

how to get started with something that looks like an ID that has my name and address on it. And I stumbled upon it. One day I went to the Museum of Natural History and there was a poster on the wall that says for, I don't know the amount, for $70 a year you can become a member. And then there was an exhibit of the membership card. And it was a nice plastic card that had name and address on it. So I paid my $70 and I had a card.

And with that, I went to a different library, and that was acceptable to that librarian, and I got my library card. So from that point on, getting a driver's license was just a matter of learning how to drive in New York. To get his Social Security card, he said that before coming to New York City, he'd worked on a farm and hadn't needed a Social Security card. To sell the story, he didn't shave for a few days and put dirt under his fingernails before visiting the Social Security office.

And it worked. He was approved. But when he tried to apply for a passport, one form he had to fill out included the question, what high school did you attend? Jack realized that they'd be able to figure out pretty easily that his answer was a lie and that that might trigger an investigation. Soon after that, Jack flew back to Moscow for debriefing and planning. He'd been in the United States for two years. One of the first things he did when he arrived was to read all the letters his mother had written him.

He also read the letters from a woman he'd been seeing before he left for the United States, Gerlinda. He traveled to East Germany to see her, and they decided to get married. She knew he'd be gone for several more years, but that this wouldn't last forever. Soon after Jack arrived back in the United States, he learned via shortwave transmission from Moscow that Gerlinda was pregnant. He remembers wanting to share the news with someone, but realizing there was no one he could tell.

The next year, in 1981, he enrolled in college. The idea was that he might be able to make more valuable contacts with a degree. He studied management and specialized in information systems. He graduated as valedictorian of his class. He got a job as a computer programmer for an insurance company, MetLife. How often were you talking to the KGB?

In person or talking, when you say talking? How often were you in contact? The contact that I had while in the United States was never in person.

That is misrepresented in movies and even in the Americans. There was a hard requirement that an illegal would never meet another KGB agent in the country where he operated. Too risky. So I got my instructions and answers to questions via Morse code and encrypted messages, shortwave radio, once a week. How did it work?

It was always the same time at 9.15 p.m. I would turn on my radio and dial the frequency. There was a specific frequency. And then listen to a call signal to understand this is really what I have to listen to. And then I wrote down the...

The signals that were delivered, they were all just digits. This Morse code, there was never any letters because it was encrypted. Encryption with letters is really weird. We did encryption and decryption via some numeric operations. And that took a while. So, you know, it started 9:15. Sometimes it took me until way past midnight to decrypt the entire message.

And my communication to the center was primarily through letters with secret writing. And there were only two sheets of paper that I could put in each one of the letters.

Once in a while I was asked to send reports about how American citizens react to certain big events in the world. And when I had those things to write, I mean, you know, there's not a lot of, you can't put a lot of information onto two pieces of paper, particularly because I had to also write them in large block letters and, you know, I printed it.

He had special pads that looked like normal notepads. But the first few pages were covered in a chemical that would transfer onto the page below it when pressed by a pencil. So he would write an innocuous-looking letter on a piece of paper, then slide it under the chemically treated paper and write his real message on top of that. And then after I was done, I put the letter into an airmail envelope

And then I had to make sure that nobody was following me. And eventually I mailed this, I put this letter in one of those public yellow mailboxes that were everywhere. And I mailed it in a spot

that was close to the fake return address I put on there. And the fake return address was always a large apartment building. So if it comes back for some reason, people would just care. They would just throw it away. There are a lot of different ways that Jack made sure he wasn't being followed. So fundamentally, this is the way it worked. It is about a three-hour travel through the city. You go from point to point to point. You walk around.

You take a train, the subway, you take a streetcar, you might take a taxi, and you could take a bus. And there has to be a reason for you to explain why you were there.

Like you go to maybe a movie theater and buy a ticket, and you go and spend some time in a museum. That was one of my favorite spots to walk around in a museum or in a department store, because in those places you can walk around and you can turn around and change direction and you see and look at the faces that...

of the people that might be following you. Normally, you know, turning while you're walking in the streets, that was a no-no. That was absolutely not allowed. So, and, you know, when you're at a bus stop, you know, see who else is standing there. Jack says that if you're being followed, it could be by a team of seven or eight people.

And at least one of them would have to be very close. They have to see what you're doing, because the reason that they follow you is to see, you know, what you're up to. If you're meeting somebody, or you're handing something over to somebody, or you put a signal on a wall or some stuff like that, anything that would indicate that you are up to no good. And so after three hours, I always knew...

that I was being followed. When I didn't know, and you can't prove a negative, but when I didn't know when I was being followed, I reported back, I saw no signs of being followed, and I was always right. The reason that I was so successful was my ability to

I had a really, really good memory for faces. And the bottom line is if you see within three hours, you see that very same face twice, you know that this person is coming. They are after you. Jack says that when he had to pick up or pass along actual objects, like fake passports to travel back to Moscow, or cash when he needed it, he'd use something called a dead drop. So what you do, first of all,

there's two people involved but they never meet. There is a spot where the spot is known to both people. This is a spot that is easily found such as a fallen tree someplace in a park that is a certain number of steps from the entrance to the park. And then there's a time when the operation takes place

Our time was always 3:25 p.m. And then there's two other spots where the signals are placed. So now the object to be transmitted is put in a container. The KGB agents always used crushed old oil cans. When I had something to transmit in a dead drop operation, I made rocks out of plaster of Paris.

So anyway, the operation starts with, let's say I'm putting the rock in the spot to be extracted. I drop the rock and then I get to the spot where I put the signal, indicates to the second person, go and get it, it's there. If that sign is not there, the person aborts, doesn't even go to the spot.

And I'm hanging out in that neighborhood for a while and then I go to the spot where he indicates that he has taken the container. And if that sign is not there, I have to go back and retrieve the container and take it with me. So communication was really awkward. And the only time I had face-to-face communication was every two years.

I went back to Moscow for debriefing and some retraining a couple of times. They changed the algorithm for decryption on me. And some rest and relaxation. That's when I had direct interaction. And when I was back at home, I felt like the old German again.

I would instinctively respond to my German name, and there was just no difference. And then when I came back to the United States, I was Jack Barsky again. He started seeing a woman named Penelope. One day, she confided in me. She said, you know, I'm actually illegal in this country. And I'm thinking, oh, you know, I really felt for her. She'd immigrated illegally from Guyana and needed a way to stay in the country.

Jack thought they could get married. And I did some research, and I found out that shouldn't be a problem because I had good American identification. I had the ID, and I had a job. I was a professional at that time. I was already a programmer. And, you know, I had what it takes. So I said, you know what? I'll help you. They rehearsed what they'd say during their interview with Immigration,

What they did in their spare time together. What their shared home looked like. None of that was necessary because when she showed up, she was already pregnant and the lady that was going to interview us said, yeah, you qualify. Jack kept his work with the KGB a secret from Penelope. They had a daughter they named Chelsea. He says that when she smiled at him, he felt something he'd never felt before.

He didn't tell the KGB anything about his American family and went on as normal, decoding messages at night and going to work every day. And then, one morning on the way to work, he saw something he hadn't seen before. It was on a supporting beam for the A train. There was a subway that went above ground where I took the train. A fist-sized red dot. ♪

Jack says he tried to ignore the signal,

He didn't want to leave. And then, a week later, someone came near him on the subway platform and whispered, "You must come home or else you are dead." He had to make a decision. His daughter, Chelsea, was 18 months old. I had to leave, and yet I didn't. I couldn't. I chose Chelsea. I chose her. I threw caution into the winds and told the KGB,

In my last letter with Secret Writing, I communicated that I'm not coming home. And the question always comes right after this when I tell people that. How do you tell the KGB that you're not coming? How do you resign from the KGB? And I came up with a really, really good lie. I told them that I was deathly ill with HIV AIDS.

And in those days, it was in 1988, HIV/AIDS, there was no cure for it. It was a death sentence. And they had no reason to not believe that. They didn't know that I had a child in this country. So they believed it. They told my German family that I was dead. And in Germany,

The files, whatever the social registry show, the German name that I operated under for 26 years died in 1988. Jack says that he started taking different routes to work and that he got rid of everything that could give him away as a spy. His encryption pad, his secret writing paper, his shortwave radio. After about three months of always looking over his shoulder...

He says it didn't seem like the KGB or the FBI were following him. I knew I was in the clear. I could live out the rest of my life sort of in the shadows as an illegal, but nobody would come after me, nobody would know about me. So after those three months, I told my...

wife, Penelope, I told her, "You know what? It's time that we work on the American dream. Save some money, we're going to buy a house." And within a year, we moved into the suburbs. And then I said, "Let's have another child." And three years after Chelsea was born, her brother was born. He'd been working at the same company as his cover for almost six years.

Over the years, he got promoted, and he and his family moved into a new house in Mount Bethel, Pennsylvania. And I commuted from New Jersey, where my job was, into that little town, and had to cross the Delaware River. There was a toll bridge. And it was on a Friday afternoon, and I'm ready to get home and enjoy the weekends and play with my kids.

And there was a traffic stop and there was a state trooper in uniform. He waved me over and I rolled down the window and he said, "State police, it's a routine traffic stop. Could you please step out of the car?"

Right then and there, I should have known that was not routine, but I didn't think about this. I step out of the car and I see this, another person, a civilian, coming at me from my right. And he flipped open and

Something like, nowadays, I don't know what it's called, the flip-open cell phone. He flipped something open that, you know, was an ID, and I didn't have to look at it. I knew what it was. But he said, you know, FBI, we would like to talk to you. We'll be right back. How did you first hear the name Jack Barsky? It first came to my attention in the early 1990s, approximately 1992, actually.

I received a communication from my headquarters in Washington that an investigation had been initiated looking for someone in the United States using the name Jack Philip Barsky and that he was an undercover agent secreted into the United States by the KGB. Former FBI agent Joe Riley. I worked counterintelligence for...

Oh, a good 20, 25 years before I got this case. And it was like hitting the lottery for me. Most of the cases we have don't come up to this level of importance. We were very anxious to know what he was up to in this country. Was he running a spy ring here?

The FBI had first gotten the name Jack Barsky from a former KGB archivist named Vasily Matrokin. Vasily Matrokin claimed that while he was working in the KGB's archives, he began copying secret documents by hand. He smuggled them home in his shoes for years and buried them in milk containers under his floorboards. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, he went to a British embassy and told them what he had.

The documents revealed assassinations, sabotage targets in the U.S., even plans to break a ballet dancer's legs. And they also mentioned Jack Barsky. Joe Riley says it wasn't hard to figure out which of the few Jack Barskys living in the United States was probably a spy. When we started doing his background investigation, we found out that this Jack Barsky was...

He really didn't have a background. He had given information to his employer that he had lived in New York State and worked on a farm, and we found from our investigation that that was false. There was no such farm, and he had never worked there. So we knew we had the right person. What did you do next? What was your first step? Well, we put him under surveillance. Why didn't you just arrest him right away?

We wanted to find out if he had any contacts here in this country before we arrested him because we weren't sure that he would cooperate. So we wanted to follow him for a while and find out what he was up to and then arrest him. What did the surveillance entail? Well, we've—

We followed him to and from work. We followed him on weekends. And also, I conducted my own surveillance. I set up a table on a country road 300 or 400 yards behind his house. There was an open field there. And I had a clear view from that road to the back of his house. And I set up a table there with books on ornithology.

and simply pretended that I was a birdwatcher. And I sat there with binoculars and a telescope, and I was able to watch him on weekends and holidays as he worked in his backyard and did yard work and played with his children. They had an above-ground pool in the backyard.

So I was surprised at how much I learned just watching him. I came to see that he loved his children and played with them in the pool. They helped him when he was planting trees in his backyard. He just seemed very close to them, and I didn't think he was going to give that up. It's amazing what you can pick up just watching people.

Did anyone ever question you about why you were watching so many birds or what birds you were seeing? No, no one did. When the house next to Jack's went up for sale, the FBI bought it. And agents took turns living there and watching Jack's movements. They also searched his car at one point. Joe says they didn't really find anything. But he did notice that Jack had a lot of classical music cassette tapes. Joe, like Classical Music 2.

While Jack and his family were away one weekend, the FBI went into their house and hid microphones in the kitchen and family room so they could listen in on Jack's conversations with his wife. Was it boring listening? I mean, I imagine that I can think about if someone put a microphone in my kitchen, I would get bored listening to me. Yes, most of it was. But fortunately, early on, I think within the first week or two,

that we placed the microphones in the kitchen, we got the conversation that was critical. It really was an argument. He clearly told her that he was here undercover for a foreign intelligence service and that he had left the service a year or two before and was no longer operating for them. So this was, you were hearing for the first time him telling his wife...

I'm a spy. Yes. And that what was critically important to us, that he was no longer actively spying. So it made no sense for us to continue surveilling him. So we finally got authorization to arrest him. Tell me about the arrest. Myself and another agent approached the car, and we told Jack to get out of the car, that we were with the FBI. And he looked up at me and he said...

What took you so long? Which was surprised us, that he would have enough of a sense of humor at this situation to ask us what took us so long. We rented several rooms in the motel for security reasons, and we took Jack to one of the rooms that we had set up, and we began initially questioning him.

He asked me every possible little thing that I could remember about my life. Childhood, upbringing, school, training, on and on, and what it was like to operate as an agent. Jack Barsky told them everything he knew. He wasn't arrested and got to continue to live at home with his family. FBI agent Joe Riley continued meeting and talking with Jack for months. He was very honest. He...

There was just something about him, and we shared certain things of interest. One was, of course, classical music, but also Jack was interested in sports. He did teach his daughter how to play basketball in the driveway of their home. And he invited me to join his weekly golf outing.

He and I would, while I was debriefing him, we'd go out on the golf course and we'd play golf and then afterwards we'd have a beer and talk about different aspects of his career as an agent. Jack Barsky and Joe Riley continued to talk even after their official communications had ended and they're still friends today. Are you in touch with anyone else you investigated?

No. I believe he's the only one. Who's the better golfer? I am. Definitive. Jack was not a great golfer, but he loved it. The FBI worked with Jack to help him become an official U.S. citizen. Joe says it was complicated because Jack already had a Social Security number, but it was under a false name. Today, he finally has a real U.S. passport after decades of trying.

And I succeeded in what the KGB wanted me to do, become an American. When his daughter turned 18, he told her about the earlier part of his life, when he'd worked for the KGB. He told her younger brother when he turned 18, too. In 2014, after he'd received his passport, he planned a trip to Germany. He hadn't been home in almost 30 years.

He learned that his mother had died. The woman he'd married 34 years earlier, Gerlinda, didn't want to see him. The child they'd had together, who is now an adult, agreed to meet. They now have a relationship. What has it been like to not have a secret anymore? I mean, to live in the open? I have some still.

I used to hide cookies because I was afraid to admit to my family that I had an addiction to cookies. I also, when I quit smoking, but then occasionally I would still smoke a cigarette, but I would do that in secret. There's something that...

that you just feel like you don't want to share with everybody. But this is nothing like big, and it is not damaging to anybody else. Okay, let's put it this way. You're probably better at keeping secrets than most of us. Oh, yeah. You know, I can still tell a lie with, you cannot read anything in my face. But I have never felt better being me than I do now.

It was a long detour, but I'm glad I arrived where I'm going to be for the rest of my existence on this earth. Well, I want to thank you so much for taking all this time to talk with us. I was so glad to get to speak with you, and thank you for making your way into the studio. Yeah, you're welcome. And question, you're an American, right? Yep. Where from?

Do you think I might be a spy? You could be. Oh, now that's the best compliment I've ever received. Are we still recording? Do we have that? Criminal is created by Lauren Spohr and me. Nadia Wilson is our senior producer. Katie Bishop is our supervising producer. Our producers are Susanna Robertson, Jackie Sajico, Lily Clark, Lena Sillison, Sam Kim, and Megan Kinane. This episode was mixed by Veronica Simonetti. Engineering by Russ Henry.

Julian Alexander makes original illustrations for each episode of Criminal. You can see them at thisiscriminal.com. And you can sign up for our newsletter at thisiscriminal.com slash newsletter. Jack Barsky wrote a book about his life. It's called Deep Undercover, My Secret Life and Tangled Allegiances as the KGB Spy in America. We hope you'll join our new membership program, Criminal Plus.

Once you sign up, you can listen to Criminal episodes without any ads and get bonus episodes each month. To learn more, go to thisiscriminal.com slash plus. We're on Facebook and Twitter at Criminal Show and Instagram at criminal underscore podcast. We're also on YouTube at youtube.com slash criminal podcast. Criminal is recorded in the studios of North Carolina Public Radio, WUNC. We're part of the Vox Media Podcast Network.

Discover more great shows at podcast.voxmedia.com. I'm Phoebe Judge. This is Criminal.