Chapters

- Al Pacino was deeply influenced by Marlon Brando and Dustin Hoffman.

- He views acting as his life's saving grace and a way to express his deepest emotions.

- Pacino's memoir, "Sunny Boy," reveals his personal journey and insights into his acting career.

Shownotes Transcript

Support for this podcast comes from Oven Grid. Tom Turnwald runs an Ohio millwork company that was started by his father and employs his kids. I'm in favor of wind farms because I'm committed to attracting talent to our community. And the school districts with wind turbines get resources that can make a huge difference in kids' lives.

Since 2012, an oven grid wind farm has strengthened the economy and contributes millions to the community each year. To learn more about where energy meets humanity, visit ovengrid.com. That's ovengrid.com. From the New York Times, this is The Interview. I'm David Marchese. When I was in college, I had a poster of Al Pacino in Scarface hanging up on my wall.

And I know that a Scarface poster is up there with Bob Marley and Dark Side of the Moon as far as cliched dorm room art goes. But I promise that my love for Pacino and that movie were real. The sheer bravado he exuded as Tony Montana was irresistible, especially for me at a time in my life when bravado was, let's just say, not exactly my default mode. Also, like a lot of people who have that poster, I just thought it looked really cool.

I came to Pacino's work in kind of a backwards way. I fell in love with his acting when I was a teenager in the 90s, and that's when he was regularly popping up in pretty mainstream movies like Scent of Woman and Heat. I didn't yet fully appreciate him as an icon of 1970s cinema, who helped bring a new level of emotional intensity and realism to screen acting.

But those 70s roles are, of course, where Pacino made his name. Think of the frazzled, yearning Sonny Wartzik in "Dog Day Afternoon," the tormented cop of Serpico, and the morally compromised Michael Corleone from the "Godfather" movies.

These are roles that all shine a bright, empathetic light on what it is to live an emotionally conflicted life. And that's not even mentioning his work in the theater, to which he's periodically returned over the years. His Shylock in Merchant of Venice is the single best stage performance I've ever seen. Over time, I've learned that there's an Al Pacino role that has resonated with every phase of my life. And learning that has been one of the real pleasures of getting older.

Pacino himself is now 84, and he's finally written a memoir called Sunny Boy. And reading it, I realized that I didn't actually know that much about the man whose performances had moved me so much. So I wanted to talk to Al Pacino about anything and everything. His childhood, his approach to acting, how he thinks about money, the fact he almost died not that long ago. And I hope that understanding the person behind these characters would help me understand why he's meant so much to me. Here's my interview, very long awaited, with Al Pacino.

I'm David. I'm the schmuck who's going to be asking you questions. Oh, you're the writer. Yeah. Yes. Oh, yeah. I thought, I thought, that guy looks like a schmuck. He must be a writer. No, no, I didn't. You know, I saw an interview with you just a couple years ago where you mentioned that you'd been asked to write a book before and you didn't want to do it because you thought the prospect of it seemed kind of torturous, that it would be too difficult to go back through your life. Here we are.

You've written a book. What changed? Nothing. I regret it. I regret it. What else can I say? I have many regrets, but this would be one of them.

Who needs to be out and about in this world, you know, putting yourself up as yet another day for another target? I mean, waking up in the middle of the night having tremors, I mean, it's really scary. You break out in a cold sweat and say, oh, my, I shouldn't have done this. I shouldn't have said this. You know, you say all those things. But I was telling the truth. That's all I know.

So in the book, you write about this quote that's meaningful to you. I think it's from one of the Flying Walendas, the famous Daredevil family. Oh, yeah. For people who don't know, share the quote. The quote is, life is on the wire. The rest is just waiting. And so for you, acting is the wire. Yeah. That's the place where life is most vibrant and alive. Yeah. And the thing that I want to understand...

as a non-actor, is why that is. You know, in acting, you get to rehearse, do another take if something doesn't go well. If you mess up, it's not the end of the world. In real life, you don't get to rehearse, you don't get new takes, and the consequences can be a lot scarier. So why for you is acting where life happens? Well, because somehow I felt as though acting

My life was saved by acting. My existence. Because I knew that I could do something. It was just like having, being able to play the harmonica or something. Or look at Buddy Rich, the drummer. My God, I was at Carnegie Hall listening to him at a Frank Sinatra concert. And he went on before Frank.

And the audience, I'm saying, oh, a drummer. We're going to hear a drummer. I heard of him, but I said, I don't want to hear a drummer. I want to hear Frank. So I'm sitting there waiting. Somebody, a drummer solo? What can that be? And it was one of those great moments in my life when I know it, because when he was finished and when he took his two sticks and then he got to the point where

He just left you with the silence. And everyone in that house, I mean everyone, stood up and started screaming. I found myself screaming. That's what he did. Because he did it his whole life. Who knows? So Sinatra comes out afterward, and he looks at the crowd, and he says, because he must have been about 65, Buddy Rich. That was an older man doing that. And so when Frank came out, he said,

See what happens when you stay at a thing. And that thing was acting for you. That's what you're saying. Yeah. And, and with Buddy Rich was the drums and with Sinatra was singing and, and you, you, you see how that, how that matters. You have to have the desire. You know,

There's a great... I don't know if you've ever seen this. I'm going to go on a bit of a tangent. There's a fantastic interview between Marlon Brando, who I'm semi-obsessed with him, and Dick Cavett from the early 70s. And Brando says, people are acting all the time. There's no difference between what I'm doing and what you, Dick Cavett, are doing. You're saying what you have to say in a convincing way to try and achieve the objective. And...

Dick Cavett says, well, you know, he just brushes it off. So there's no way that you could equate what I'm doing with what you, Marlon Brando, are able to do. And you can tell Brando, I don't know why, but at some point he soured on the idea that acting was this special endeavor. And he said, you know, everyone's an actor. It's glorified lying. That's what it is. What do you make of that? I think it's glorified telling the truth. Yeah. It's different. Yeah.

You know, and I think what truth you're going for, I don't even know, but it's not lying. It's finding the truth. You write in the book about sort of what a bolt from the blue Marlon Brando was when he came along. And then you also mention sitting in a theater and watching The Graduate. And I think the way you put it was, you know, you're watching Dustin Hoffman break the speed of sound barrier in that film. But do you think since that time,

Have you seen anyone who you thought did something new in acting? Well, of our time in the 70s, I don't know. A lot of us, I think, were influenced. But I have to say, with all modesty, all the modesty I can muster, when I was a kid, 13 years old, I remember finishing a performance of a play I was in.

And I don't know whether I did well or not in it. Who knows? This guy comes up, older man, an adult, comes up to me and says, hey, kid, wow, you're the next Marlon Brando. So, you see, there's the thing. You know, you say, and people throw things out, like, who's the best one? Marlon himself would say, I don't want to know the best. There is no best. He was an original. He was an original. Who was like him? Do you think you were original?

I just could say offhand, I don't think so. I don't know. I don't want to be, you know, I just, I'd be honest as honest as I can be, but I don't know.

Let me ask you a very specific question about one of your performances. Yeah, please. You know, I went back and rewatched a ton of stuff. Poor guy. So in Incentive of a Woman, okay, you know, there's the big climactic monologue, you know, that if I was the man I was five years ago, I'd take a flamethrower to that place. So the aspect of that

I'm just picking this as one example of a thing that you are able to do that is, I find, so compelling as an actor. So you're giving that speech. And even in the space between words, we can see little micro emotions just sort of flash across your face. You know, it's...

You can telegraph that Colonel Frank Slade is having thoughts in those moments, even when he's not saying something. Oh, that's right. And I think, is that something that you're in conscious control of? Or is that just you're exuding something in the moment that is beyond your control? Yeah. That's the one. It's the latter. I would say that's what happens. I have always felt that to free the unconscious...

to allow that freedom. That's what my favorite quote of Michelangelo's, free me of myself, Lord, that I may please you. That freedom, that's the whole idea of relaxation and everything else, which is once you get into that freedom, the unconscious goes to work. I just heard the other day that someone was able to hear the big bang. You can hear it.

Yeah. That's what they've done. I mean, when I heard, my son told me, I couldn't believe it. I felt so great. He says, you want to hear it? I said, no, no, no. Just the idea that it's out there and it's kind of muffled. It happened. We're real. We exist. This is the greatest thing that can happen. What information? I went to bed high just from that.

But as far as your question goes, I know I go off on things. Let me tell you, pal. You know, an actor was telling me that he attributed this to something that he thinks Meryl Streep was quoted as saying, which is that, you know, every good script has a scene that makes the actor think like, how the hell am I going to do that? Yeah. So what's an example of a scene that really you thought, how am I going to pull that one off? Oh, yeah.

Let me see. I know I've had that feeling before. When we get to that, what's going to happen? Oh, my God. What about killing Salazzo in Godfather 1? Was that one of those scenes? Salazzo? No. I mean, it's easy. Killing Salazzo? I mean, you know, I just don't want the gun to go off. You know, I mean, yeah, you just go there and...

I mean, my friend Charlie told me. Your friend Charles Lawton, yeah. Yeah, my friend Charlie Lawton. How? How are you going to go in there and be the don of all these guys, these great actors like Duval and all, you know, all these people around that thing? You know, I was just homeless a couple of years before that. So I said, well, I mean, you know, I don't have... It's in the script. You know, I mean...

I tell somebody you're out, you're out. You know, I don't want to say it a million ways.

You don't go, you're out. See, it's like... Do it three different ways right now. Show me some... Do you're out three different ways. No, I just don't do that. Actors don't... It's like saying... Wait, you don't like it when I say, act, monkey! I'll say to you, interview, interview. Go ahead, let me see you interview. Not me. Tell me about your childhood. Tell me about your childhood. What's your private heartbreak? I can do it. I hate to be shown up like that.

Well, you know, in the book you say that directors have insulted me throughout my life. Yes, yeah. Oh, yeah. Many of them have. Tell me one. Many people have. A great director, what was his name? The guy who directed the great Mozart film.

Amadeus. Amadeus. Yeah, Milos Forman. Milos Forman. You know, he's so great. And I'm having dinner with a few people, and he just came in. How do you do this?

fucking scoff face. You do dog day afternoon, then you do the fucking scoff face. You know who else said it? Who? My favorite, Lamont, Sidney Lamont said, Al, how do you go in there and do that crap? And he was so mad. And I kept thinking, I don't feel that way. So, you know, if I felt...

I actually, I love their passion. I have to say that. I'm not being like some Mother Teresa or something. You're being nice. No, I'm not being. Somebody says, how do you do that shit? You say, I love your passion. Yeah. You're enlightened. Yeah. And thank God, merciful, that I can say today it's one of the biggest films I've ever made.

Yes, Scarface. You know, it's interesting that you mentioned Scarface because... It keeps going. When I think of Scarface, I wonder if in some ways it's not...

purely in terms of your acting style, a pivotal movie for you. Scarface was the first time you kind of really went operatic over the top. The question is if in doing that, it changed something about your acting or opened something up in you. Because if you look at the roles you do after, I feel like you're much more likely to sort of go big than you were before. Yeah.

I got that reputation. Do you think Scarface opened something up in you or sort of changed what you did in some fundamental way? Well, I...

You know, like I say, look, I'm sorry, but some of the early stuff I did in school, 14, 15 years old, when I did it, it was in those plays. That was still the best work I ever did, or what I think the best work. It's not the best work. It simply was the most inspired work I had done. You know, I didn't know what I was doing. The most inspired work you did was a 14 or 15-year-old kid? I think so. I think so, because I was so in it. And that's why the teacher came and talked to my mom.

and came to my house to tell her about me and that I should pursue this thing. And that was when I was in high school performing arts. And the first things I did were absolutely absurd, and the kids in class were laughing when I would perform like that.

But as time went on, I got a little bit of the drift of it and I did some things. But what I'm getting at is Scarface was done that way. Scarface came from a way, a place that was different than anything I'd done before. That's true.

You must get directors who have said to you at some point, thinking about other performances you've done, something to the effect of, give me more Al Pacino. What do you think they're looking for when they say something like that? Go louder. I don't know. I couldn't tell you. I mean, bring it up to, I don't know. Nobody's ever said that. Oh, they did say, you know, things to me in the theater from time to time. And I had to adjust to directors. Say things like what?

I want to say things like, you see, somebody, one director came up to me once when I was young. You have to understand, I was young here. And he came up to me and said, you see, the character did this and the character comes in. And then, you know, he's feeling this way here and he does this. So I said to him, I just, I mean, I said, well, you seem to really relate to this person. I said, he said, what? I said, yeah. I said, maybe you should play him. Dead silence.

I don't like that kind of talk. That kind of talk is, you know, a director who's directing you and is helping you with your part is telling you how to do it. I don't understand that. Then why did you cast me in the first place? Well, what's a great note that you got from a director? One of the best notes I ever got was from Lee Strasberg when we were doing Injustice for All. I came in and I was doing a scene and then Lee just leaned over to me and said, darling,

You can learn your lines. Seems like good advice. Great advice. In the book, there's an offhand line in the book. You say, there's the general belief that I'm a cocaine addict or was one. I've never heard that before. I don't know. I assumed it. I made a mistake. These assumptions is what is going to kill everybody because assumptions turn into opinions. I heard it somewhere.

They're shocked when they find out I don't take cocaine. I never took it in my life. It's the kind of drug that a person like... But who's shocked? Who are these people? I wish I knew, but you know, I have a grapevine over at my house, and that's where I get it. I'm not the kind of guy who should take coke. Any upper, I don't need. I'm up. Clearly. Yeah. In a bunch of your movies...

There is really an opportunity. Usually it's a monologue. Yeah. Where you just really get to

do your thing, you know? So I mentioned, send if a woman has that or, oh, remember in city hall, there's the great speech. I choose to fight back or any given Sunday inches. The difference between live it and die it or I keep, oh, devil's advocate, right? There's a God. He's an absentee landlord. But when you, when you see those parts in a script,

Some part of you must know, when I get here, I am going to give the thing that people want, right? Exactly. That's what they came for. A lot of people, a lot of people don't like it, I must say. And I sometimes go too far, I think. And I don't think through it enough. It comes to me a little easier because I love words. You know, I love to say words. And I really do think I can...

I can do with some taking it down a bit. I really do. It's a confession. But hey, if it's ham, as long as it's not spam. That's what they used to say.

Al, I also want to ask you about the subject of money. Because in the book, you write about growing up really poor and also about how, I think it was in the 2000s, you lost a bunch of money because your accountant ripped you off. And before that, it sounded like you were, let's say, spending lustily. I think $300,000 or $400,000 a month was the figure you gave. You said your landscaper was getting $400,000 a year. And all that made me think,

What is this man's relationship with money? Oh, no, you don't want to know. It may be catching. In what ways? You'll go down the drain for sure. But in what ways did growing up the way you grew up, where money was not readily at hand, do you think shaped your relationship later on with money? You know, I'm the kind of person, I think, that if I don't understand something very well, I just avoid it.

There's no sense. You know, if I have a need to learn it, you know, actually, you know, my father, who I, you know, I didn't know really, he was an accountant and a very good one, apparently. And, you know, so he sort of knew he'd have to, wouldn't he? I mean...

But I moved away from that only because I was always into my work or other kinds of things that had nothing to do with money, except, you know, a fool, whatever that saying is. That was very applicable. A fool and his money are soon parted? Yes, are soon parted. Also, you write in the book about how

You know, you just were started to take more roles often because, you know, they're paying gigs. And my question about that is, how do you calibrate how much of yourself to put into a performance in that type of circumstance? Because, you know, it's one thing if you're doing

you know, Serpico or Dog Day Afternoon or even Sea of Love, it seems to me it would be impossible or foolhardy to put the same amount of energy and detail into, I don't know, Righteous Kill or 88 Minutes or something like that. So is there like a conscious calibration that happens on your part? Yeah, there would have to be. But everything I do, I try to do the best I can.

So that would require certain things. And, you know, people maybe sometimes will scratch their head and say, what is he doing? Why are you going through all these, you know, machinations in order to do this role? I mean, and I understand that, but that's the way I've always worked, you see. So I approach these things like, okay, what can we do with this?

So, and finally, I enjoy the whole idea, or maybe make myself enjoy the whole idea of being in the editing room or the afterglow or the, you know, after you do it, you have to then fix it. You know, sometimes I would actually even put my own money back into this film I did for money. So I would do that in the effort to see if I can get it to mediocre.

then I would be accomplishing something. And I never did. And I have to say about films now, I don't know, to me it feels like the last 20 years, but pretty much films are changing because of the streamers. Yeah, how so? Well, there's more work for everybody, but the quality of it has changed a little bit because it's an output. And for one thing,

Things seem to be a little more rushed, which means everything is operating on a, I don't want to call it a treadmill, but on that thing that goes through the, you know, Charlie Chaplin film. What is that thing? Like a conveyor belt. A conveyor belt, yeah. So, you know, you know that you're a part of something. And sometimes some of those movies, you try to bring them to,

a level where you are trying to find what's most interesting in a film, to bring it out and to expose it and allow it to flourish. That's what you're after, so that it communicates. I was reading Richard Burton's diaries. You ever read those? No, I did. A little bit, I did. I love Richard Burton. Yeah. I know you love him. And in his diaries, he really suggests that

He felt like he underserved his talent by acting in a bunch of stuff that was beneath his skills. Is that a concern that you ever had? Or how did you guard against it?

when sort of in the 90s and beyond, you then said, I'm not just going to sit around for years waiting for the perfect role. I'm going to just take stuff. And sometimes the stuff's probably not going to be blue chip, but I'll try and make it as good as I can. Yeah. But is there ever a concern that you, or was there ever a concern that it might tarnish the gift to take material that

maybe wasn't at the level you were capable of? I really don't think so. I think I looked for something that I could relate to and that I would feel inclined to want to play it. That feeling comes to say, I have an appetite to do this. See, athletes, it's clear with. You lose your fastball. Yeah, you lose your fastball.

You don't get down at first as quickly. You know, your eye is not, and you know you're going. Sports have that. But the actor has other roles they can go to, other roles that, you know, are, you know,

You say, I'm doing Lear. I'm doing King Lear. I'm doing an adaptation of a film of Lear. And I want to. And I'm trying to stick to those kinds of things because I went through a period of time, and you always do in this. You see it. Everybody has it. Other actors have it in my position too. They do things sometimes differently.

Sometimes for financial reasons, but sometimes also because you just don't want to sit around and you want to find something that can get busy. I'm sure other actors would say other things about their interpretations of different things they did. Some actors can't articulate things. I was one of them. I still am in a way. There's sort of a thing about articulating what you're doing as if you're being found out.

You know, that's why I didn't care for interviews much when I was young. A long time, yeah. Yeah, because I thought what they did is they exposed a part of you that then people reflect, and then when they see you in a character, they think, you know, now they all think, when is Al going to yell? I bought that ticket for Al to yell. Is he yelling at me? I need it. I need someone to talk to me that way. Yeah.

But what changed your mind then that made you feel comfortable pulling back the curtain by doing interviews and things like that? Why did you change your mind? Well, I mean, I could relate it to Picasso for one thing. Picasso, they did this great documentary on Picasso. And he goes and he makes a painting. You see him make it. And then he takes it and he holds it up beside him.

And there's Picasso and there's the painting. And it's like you have two people there, you know? It doesn't matter because the painting exists. That's what I thought. And I think it made me think a little bit. It made me think, well, you know, if Picasso can do that, wow. You know, I'm this person that you're seeing now. And I think, I'm partially, I'm doing an interview. I'm not this way when I go downstairs. I mean, I wouldn't have any friends and I'd be, you know,

I don't see it. But I do feel also doing the book has opened me up a little bit, too. You know, you care a little less as you get older, too. I don't mean to bring that in, but you do. You sort of say, hey, man, you know, say what you have to say. You know, what happened? Well, so has aging been comfortable or uncomfortable for you?

God, I don't know what the hell aging is. It seems absurd and crazy. I don't even understand it. You know, I wish I had something. I sometimes say, you know, why can't I find some steroids around that won't kill me? You know, I'm just thinking about who would I know that has steroids and keeps living with them, you know?

Because I took some when I had the bad COVID, the first time I had it, where I sort of... You almost died, yeah. Well, they said my pulse was gone, and I thought, that's enough. But I thought it was so, like, so well. You're here, you're not. You're here, you're not. And I thought, wow, you don't even have your memories. You have nothing. Strange porridge.

Towards the end of the book, there's a couple of very moving passages about your youngest son, Roman. Yes, yes, yes. And you're sort of musing about he's, what, one, one and a half, something like that? Yeah, he was less than that when I was musing about him, you know. He's coming to the world a little more now, you know. He's learning things. How much of the desire to set your story down was about wanting—

him to be able to know what your life was? I don't know. He will. I mean, you know, that's the way the world, whatever, which way the world goes. You know, if we're talking about 20 years from now, who can speak to that? I mean, that's, I can't. Can you predict anything now? Well, I just wondered if some part of you is thinking you wanted to have your story in your words,

for him, um, because he's so young now. And well, that's one of the reasons. Yes, of course. Yeah. Yeah. And, uh,

That has been a campaign for me to get a little older, you know, and stick around a little longer if it's possible. But I got to say, you know, and this is probably more sort of psychoanalysis than you're interested in. Is it not possible that on some level, having a child at 83 years old is a reaction to the recognition of your own mortality? Yeah.

Wow, that was something. I don't know. I have to think about that. I got four children, you know, so I'm happy about that. But no, I don't know. Maybe I don't even understand it. Understand what? Well, you know, like when I saw the little baby there and the way he was,

You just, you look at it a little differently now. You know, you look at it like, what is this? This is so amazing. That's why I was so excited by hearing the Big Bang. Because I thought, my God, I'm not going to die. I don't mean literally. I mean spiritually. Look at that. There's something out there that's bigger than us.

You can't say better because you don't really know them, but something's out there going on that's more than we understand. Let me ask you one last one for this time. If I were going to go away and figure out how to play Al Pacino... In your life or in a movie? Either one. What's the secret to portraying you? Well, I think you should just go to some of those metal houses and study some of those people there. ♪

After the break, Al shares more about his near brush with death. I opened my eyes and everybody was around me. It's the first time that ever happened. And they said, he's back. You know, he's here. Banking with Capital One helps you keep more money in your wallet with no fees or minimums on checking accounts and no overdraft fees. Just ask the Capital One bank guy. It's pretty much all he talks about.

in a good way. He'd also tell you that this podcast is his favorite podcast, too. What's in your wallet? Terms apply. See CapitalOne.com slash bank. Capital One N.A. Member FDIC. Hey, I'm Tracy Mumford. You can join me every weekday morning for the headlines from The New York Times. Now we're about to see a spectacle that we've never seen before. It's a show that catches you up on the biggest news stories of the day. I'm here in with

We'll put you on the ground where news is unfolding. I just got back from a trip out to the front line and every soldier... And bring you the analysis and expertise you can only get from the Times newsroom. I just can't emphasize enough how extraordinary this moment is. Look for The Headlines wherever you get your podcasts. Hi, Al. Hi. Hi.

You know, I have a handful of questions. Some are follow-ups to stuff we talked about before. Some are different. Oh, I love it. You know, we started to talk to each other, and you're going to find, as we all find, we're in different moods every time we speak. Every day, I change. Well, how's your mood today?

I have a mood that seems a little bit better than the last time we spoke, and I don't know why. I feel I might be a little more articulate today. Wishful thinking, but I think I might.

We'll give it a shot and see how it goes. But, you know, I'm thinking about how you had made this kind of offhand comment earlier about how you're not the same guy talking to me as you are when you go downstairs in your house. And, you know, if you were that same guy, you wouldn't have any friends. But I want to know, how is the guy downstairs in your house different from the guy talking to me? Who's that guy?

I'm sorry, but I can't answer a question like that. I don't understand what you're talking about, actually. I really don't. I'm in the moment, and whatever's in the moment is who I am. When I'm going down the stairs, I'm obviously thinking of other things, but I have to really think about falling down the stairs. These are the things...

I think about it when I'm sitting and thinking about some, you know, I have a lot of things I can think about. I have, you know, four kids. I have all kinds of projects and, you know, I'm occupied. I don't know what else I could say. The guy I am now is talking to you. Yeah. I guess it's the subject that matters. I don't,

You're asking me an impression of what I am. Do you have an impression of what you are? Oh, yeah, for sure. Really? Will you objectify yourself? Okay. I don't think about that. Sometimes I even see myself in the mirror and I get a little shocked at first. That happens. Well, you know, it's interesting for me to hear you say that. I know you're getting at something. You started getting at it.

When did we speak? This week? Yeah, a couple days ago. Oh, okay. You started getting into this very thing. And I thought, I don't know what this guy is doing or where he's taking this thing, but I'm sorry. I don't know how to comply.

Oh, no, you don't need to apologize. I think the thing I'm getting at or trying to get at is when you said back to me, like, do you sit there and have some, like, objectify yourself and think I know who I am? And I said, yes. And I wonder if that's the difference between someone who's an actor and someone who's not. Maybe someone who's able to inhabit other personalities has a greater sense of malleability about. I actually had that thought.

When I asked her, I said, I think maybe he might be thinking because I'm an actor that I inhabit other characters. I don't know. You know, you call on, there are some actors who are more or less, you know, mimics. They're more on the mimic side. And there are others that, it's a form of mimicry in some way. You know, you're pretending to be somebody else.

But then you're not pretending anymore. You absorb it enough times and you become it. But that requires a certain amount of focus and acumen and time and patience. Everything to me is time. It's time. It's like anything. You know, you paint your house and you start painting and you start painting one of the rooms.

And then you go and move again, and you paint another room, and then you paint that room again. And then what happens is the way you painted the first time, the first room, by the time you've painted about 40 or 50 of them, you're a different painter. That's what I think. Wait, but you're working on a film adaptation of King Lear, which is obviously a mountain of a role, and one you've never played before, right?

No, I've never played it. I've stayed away from it forever. Yeah, tell me why you've stayed away and why you're taking it now. Well, why I'm taking it now is I've been... You know, people have been encouraging me to do it. Ten years ago, I remember thinking I had no interest in it. And then I started reading it all the time. And I saw it a few times, too. And I got to know it. And it wasn't until...

I realized things. I got older, and some of the things that I... Not that they're easier, but I understand them more. Well, so how are you understanding Lear? Yeah, I can't talk to you like that. I understand Lear, but that's my secret.

I want to go back to your COVID near-death experience. I know you described this a little. I love to revisit. Let's revisit the time you almost died, yeah. Just tell me about what happened.

Well, I'll tell you what happened was I felt not good, unusually not good. And I had a fever and I was getting dehydrated and all that. So I got someone to get me a nurse to hydrate me. I was sitting there in my house and I was gone like that. So you just went from consciousness to no consciousness.

Absolutely gone, yeah. So then they looked at my pulse and I didn't have a pulse. It probably was very, very low and they got panicked right away. In a matter of minutes, I guess, or whatever it took, they were there, ambulance in front of my house and I had about six paramedics in that living room. And there were two doctors and they had these outfits on

that looked like they were from outer space or something. So it was kind of shocking to open your eyes and see that. I opened my eyes, and everybody was around me. It's the first time that ever happened. And they said, he's back. He's here. Well, did that experience sort of have any sort of metaphysical ripples for you? Yes, it did. It actually did. I didn't see the white light or anything like that.

There's nothing there. As Hamlet says it, to be or not to be, the unknown country from whose born no traveler returns. And he says two words, no more. It was no more. And I don't like that, that there's no more. It's gone, you're gone. Now, I started thinking about that and I never thought about it in my life.

But, you know, actors, it sounds good to me to say I died once. It's not my death. What is it when there's no more? I mean, you do have this body of work that you know that people will be going back to for at least a little while. Is that consolation at all?

Well, yes, and the kids, you know, having children and all is a consolation. And it's natural, I guess, to have a different sort of view on death as you get older, you know. It's just the way it is. I didn't expect it. I didn't ask for it. Just comes like a lot of things just come.

Well, I don't want to linger in morbidity, but... I don't find this morbid, man. It's not morbid. No, no, but I have one more perhaps slightly morbid question, but, you know, your youngest son, like when you're not around, what performance of yours should he watch to see what his old man was capable of? I think he should start off with Adam Sandler's. Oh, Jack and Jill. What was that? Jack and Jill. I think that's funny.

Adam Sandler is just the greatest guy. He's just become a great actor. And I really enjoyed so much his company. And it came at a time in my life that I needed it because it was pretty much after I found out I had no more money because my accountant was in prison and I needed something quickly. So I took this

There's this thing I do in that film, they got me doing, it's a Dunkin' Donuts commercial. You know how many people think I actually made that commercial? I mean, it's just so unfair. - You did it, you took the role. - Yeah, but afterward, at the end of it, I say to Adam in the scene, what I say to him, "This does not go on."

No, he says, no. I said, just no, it won't go on. I won't put it on. But he put the film on. It's always been all over the internet. I thought it was funny that, you know, you said your, you thought your best performances that you ever gave when you were, when you were a kid, like 14 or 15, because you felt so free. Do you feel freer now at 84 as an actor than, than before or?

You know, it always depends on a couple of things. It depends on the role. It depends on who's doing it with me. It depends on who's, you know, directing it. I do feel free with it. And usually when I make films, I'm not very happy. I just, they can be tedious. But I found a new, as soon as I found a camper,

that you can like go to your camper, just sit there and do whatever you want. I even get television in there. It's like, oh, you know, the camper taught me how to watch TV. What do you watch on TV? You can't get me away from television. Well, I go to YouTube, YouTube or anything and everything. You know, there's so many things on YouTube. I mean, you got Ibsen, you got Chekhov, you got Strindberg, all on the internet.

I even like TikTok when I see it from time to time. Some of the things just TikTok. Yes. I mean, I saw like a 14 year old girl who was deaf her whole life and they do something with her and she's actually starts to hear for the first time about that.

Sometimes the rescue, the dogs in rescue, you watch the guy go in there and bring this beautiful, sad dog back to being somewhat aware of things. Well, I love that stuff. Are you going to join TikTok? Absolutely not. I wouldn't know how, first of all. Who do I call up?

I want to go all the way back to the beginning. I got the sound of the Big Bang queued up for you. Are you ready to hear it? No, please don't give it to me. Did you find it? Yeah. Oh, my God. Oh, please don't give it to me. I don't want to hear it. I don't want to hear it, man. It gets me so stirred up. I can't even hear it. I'm terrified of it. But I love it so much. It's there. Something started this. Something started it.

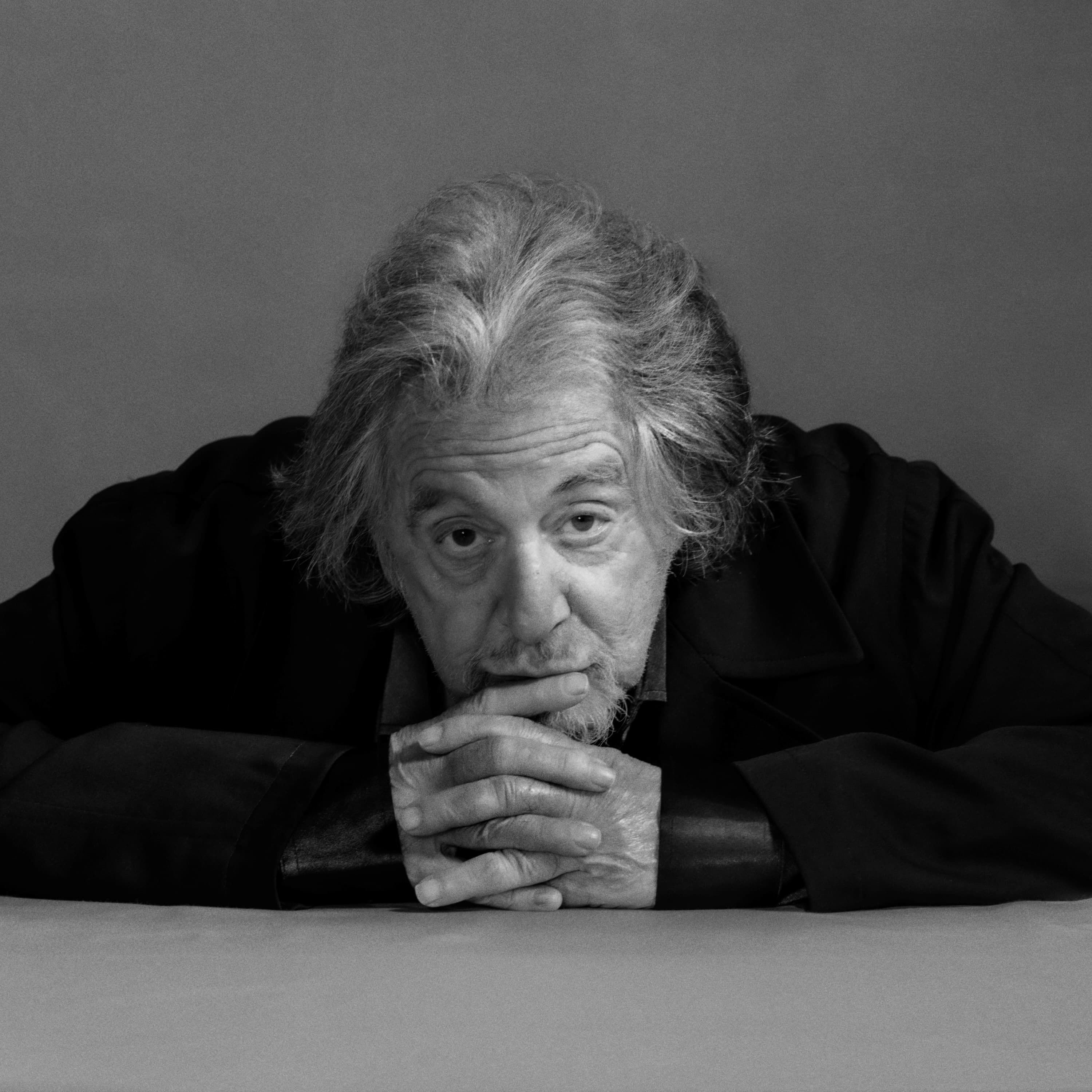

But hearing the fact that you are there, you are there. And that's the amazing thing about it. I just saw it. I saw the whole opening. Oh, my. I'm going to do Leah like that. That's Al Pacino. His memoir, Sunny Boy, publishes on October 15th. This conversation was produced by Wyatt Orme. It was edited by Annabelle Bacon, mixing by Efim Shapiro.

Original music by Diane Wong and Marion Lozano. Photography by Philip Montgomery. Our senior booker is Priya Matthew and Seth Kelly is our senior producer. Our executive producer is Allison Benedict. Special thanks to Rory Walsh, Renan Barelli, Jeffrey Miranda, Nick Pittman, Maddie Maciello, Jake Silverstein, Paula Schumann, and Sam Dolnik.

If you like what you're hearing, follow or subscribe to The Interview wherever you get your podcasts. And to read or listen to any of our conversations, you can always go to nytimes.com slash theinterview. And you can email us anytime at theinterviewatnytimes.com. I'm David Marchese, and this is The Interview from The New York Times. ♪